Inspired by the PI diaries from Dr Ai Taniguchi’s superlative L’IMAGE project, I thought I’d have a go at jotting down my experiences and experiments in conducting child language acquisition research with Real Live Children. NB: I’ve included a short glossary and references section at the end of each post – take a look there if you’re confused or want to know more…or both.

It’s been a wee while since I have been able to run experiments with children – early 2018, I think – thanks to Covid-19 (heard of it?), parental leave, and 1001 other pressures and projects to focus on. But in the last year I have acquired a fabulous new colleague, Dr Emma Nguyen, who also studies child language, another wonderful colleague secured an open-ended position at another not-too-far away university (Dr Johannes Heim, at University of Aberdeen) and the LingLab at Newcastle has gone from strength to strength, gaining more funding for fantastic resources, equipment and training. With all these things in place, we’ve finally got our Language Evolution, Acquisition and Development research group up and running and tucking into pastries together every fortnight. All of this provides a firm and supportive foundation for finally getting back into the experimental groove.

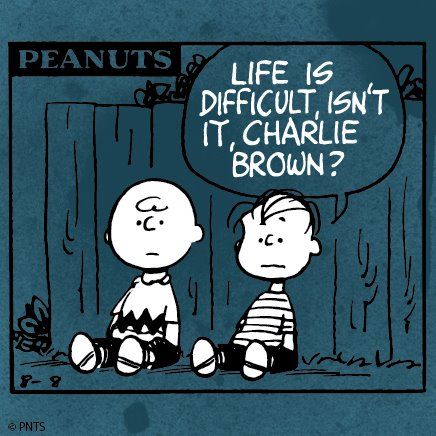

And I did get back into it, this past week! Johannes and I have been planning an experiment to investigate how children produce non-canonical questions in English – what grammatical structures do they use, what intonation patterns do they produce, and do they produce co-speech gestures alongside them? By non-canonical questions, we mean questions that don’t just ask for some information that the speaker wants to know. I’ve got an example of a canonical information-seeking question in (1), and three types of non-canonical questions in (2-4): tag questions (2), negative biased questions (3) and suggestion-like why questions (4).

- Do you like flowers?

- You like flowers, don’t you?

- Don’t you like flowers?

- Why don’t you pick some flowers.

Questions like (2-4) are a totally natural part of conversation but differ from (1) in lots of ways. (2-4) all have negation in them (n’t) and they’re all pretty bad in “out-of-the-blue” contexts. That means that the person who says (2-4) has some kind of conversational agenda or prior knowledge that they’re basing their question choice on, where (1) can simply be asking for some information that they’re lacking, without expecting a specific answer.

Questions (2-4) are far less frequent in conversation than questions like (1), and can vary in their frequency in different dialects (tags like (2) are used around nine times more often in British than in American Englishes, for example) and to different addressees (suggestion questions like (4) require the speaker to be in a social position to be able to offer advice). All 4 types of question are major topics in formal linguistics, where linguists take utterances and judgements by adult English speakers to try to work out how the meaning of each type of question comes about from its syntax, semantics and pragmatics. But tag questions in particular have been neglected in studies of *child* English. Enter Johannes and me.

Now, I’ve already done some work on questions (2-4) in child speech from the CHILDES corpus, but (a) a lot of those corpora are American English and (b) the sampling is pretty infrequent in them in general, so we didn’t get an awful lot of data (just under 650 questions from 67 children – this compares with over 20,000 instances of n’t across all sentence types). Also, we could only work from written transcripts as most of the corpora didn’t have recordings available, so we had no information about how children produced these questions.

So we need to turn to experiments. As I mentioned above, we were interested in taking a multimodal approach to these non-canonical questions – this means we started out interested in morphosyntax, but also prosody [intonation] and gesture [hand, face and body movements).

How did we get on? Well, come back for diary #2 to find out…

Glossary

CHILDES: Child Language Data Exchange System, available at childes.talkbank.org. A fantastic resource set up and run by Brian MacWhinney at Carnegie Mellon University containing hours and hours of transcripts, audio and video of children acquiring different languages.

Morphosyntax: a subfield of linguistics interested in the grammar of morphemes at the level of the sentence. Morphemes are units that may constitute single words or may combine with other morphemes to build words. The study of morphemes at the word (or lower) level is called morphology. From the Greek units morph- (shape, form), syn- (together) and tassein (arrange), via German Morphologie, Latin syntaxis and French syntaxe.

Multimodal: literally ‘many modes’, this means looking at language not only in terms of the words/structures used, but also prosodic features like intonation, co-speech gesture, and context.

PI: Principal Investigator. The researcher leading a study; also often the person who applied for and won the funding (if applicable).

Prosody: The study of rhythm, stress, timing, tones and tunes of language.

References

Frequency of tags in British and American Englishes: Gunnel Tottie (2009). How different are American and British English grammar? And how are they different? In Günter Rohdenberg and Julia Schlüter, eds. One Language, Two Grammars? Differences between British and American English (pp.341-363). Cambridge: CUP. Taken from p. 354.

My work on tag and biased questions: Rebecca Woods and Tom Roeper (in press). Children’s acquisition of “high” negation: a window into the logic and composition of bias in questions. To appear in Manfred Krifka et al, eds. Biased Questions: Experimental Results & Theoretical Modelling, to appear with Language Science Press. Preprint.