Strange things are happening in the world of education. To the benefit of absolutely no-one, STEM subjects are frequently held up as the only ones worth studying, while technological advances (and misadventures) demonstrate the need, time and time again, for a nuanced understanding of human beings, how they think, and how they move through the world. In short, we all need more of the arts and humanities.

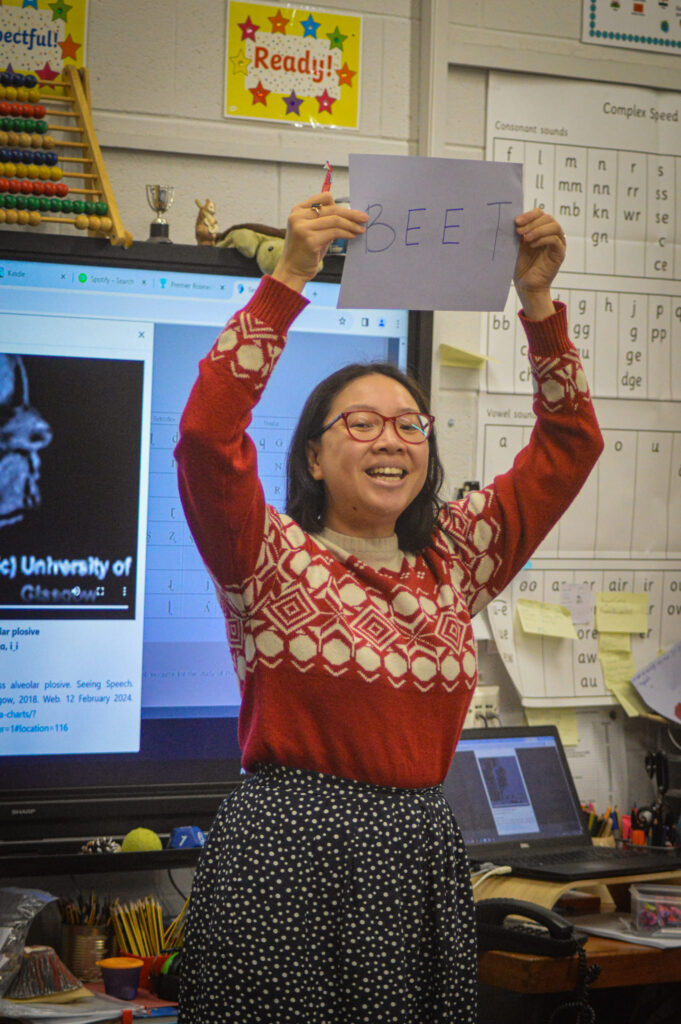

As a discipline that straddles both STEM and arts and humanities, we have a unique opportunity in linguistics to disrupt the current binary discourse (STEM or bust) and muddy the waters wherever possible. Linguists frequently apply the scientific method to that most human of behaviours, language, but just recently, my fabulous colleague Dr Emma Nguyen and I had the chance to squeeze some awareness of being human into a science space.

The scene: STEAM week at a very lovely local primary school. The brief: chatting to year 3 (ages 8-9) about muscles. The topic? Well, as linguists, we were duty bound to present the group of muscles that gave our field its name* – the tongue. The tongue is crucial for spoken language, but what did our 8 year olds already know about how it shapes language sounds?

By year 3, children in English schools have had a few years of instruction in phonics – a system that teaches the most common associations between sounds (phones) and letters (graphs) to help children ‘decode’ written words. The principle is that by sounding out a word’s constituent graphs and blending the corresponding phones, children can break into written English without needing to rely (too heavily) on memorising full word forms.

However, the phonics schemes we’ve come across as parents or in conversation with schools spend very little time on explicitly describing how, where and with what body parts sounds are made. Some schemes even include mascots that make speech sounds despite having no lips or teeth. Teachers say that the sounds made at the very front of the mouth like /p,b,m/ might elicit some discussion about the lips, and sounds like /f,v/ are talked about in terms of lips and teeth. But sounds at the back of the mouth like /k,g,ŋ/? No-one is sure how to talk about how these sounds come into being.

So the tongue and the back of the mouth are as foreign to our year 3s as the Moon. But unlike the Moon, we don’t need a rocket to find out more about them. Instead, we used a little trick sometimes employed in first year university phonetics classes (that would also buy us a bit of notoriety – more on that later).

That’s how the tongue makes sounds? Sweet!

We ran a little experiment, turning Willy Wonka by handing out lollipops** (or lollipop sticks to anyone who didn’t fancy a sweet). We instructed the children to put the lollipop toward the back of their tongue, then we all read together words with different vowel sounds in them.

Lolly stick demo from me…

Photo credit: Hotspur Primary School

Emma directs the sweet chorus

Photo credit: Hotspur Primary School

This helped demonstrate how open front vowels like /a/, where the lolly (and tongue!) move down and forward in the mouth, differ from closed back vowels like /i/, where the highest point of the tongue is right close to the back part of the hard palate (resulting in a few lollipops stuck to the roofs of mouths).

Sweets in, tongues out

Photo credit: Hotspur Primary School

Surprising level of patience and resisting of temptation…

Photo credit: Hotspur Primary School

The kids were amazed at how mobile their tongues were, while we were amazed at how disciplined they were at not chomping the lollipops at the first opportunity. NB: the sweets were not a gratuitous choice! They stick beautifully to your tongue to allow you to focus on how your tongue moves without actually inhibiting it from doing so normally. Until it gets stuck to your palate after a close sound, of course, which will happen if you’re (a) eight years old or (b) narrow-of-mouth, like me.

The experiment demonstrated how place of articulation, or the point at which the tongue, teeth, or lips close or come close together, is a really useful way of distinguishing between sounds, and helps us differentiate words like tap and cap. Tap’s initial /t/ sound is made by the tip of the tongue closing up against the alveolar ridge, just behind the teeth. In contrast, cap’s initial /k/ is made by pushing the back of the tongue right up against the velum, or soft palate. It is the position of the tongue alone*** that prevents misunderstandings about wearing bathroom furniture as a hat.

We also showed the kids some MRI videos from the fabulous website Seeing Speech. These give a fantastic insight into the flexibility and precision of the tongue from a side-on view (pretty hard to achieve any other way), with the added gross-out value of demonstrating just how enormous your tongue actually is.

What other muscles affect how sounds are made?

Some children noticed, though, that place of articulation is not the only thing that differentiates sounds. This led to discussion of another set of muscles and tissues that help us produce speech – the vocal folds. We placed our hands on our throats and made the sounds /s/ and /z/ on repeat. The buzzy feeling of /z/ is due to vibrations in the vocal folds as air is forced between them, and this is called voicing.

Photo credit: Hotspur Primary School

To get a sense of what voicing really looks like, we played another video, this time of vocal folds in action from above, and then we got creative. Using a paper cup and elastic bands, we created our own voice boxes, using straws to blow across the elastic-band-vocal folds to cause them to vibrate, and even stretching them with our fingers to create higher pitched sounds. This activity was inspired by one described on howtosmile.org.

Photo credit: Hotspur Primary School

One of the year 3 form teachers is also the school’s music teacher, so we compared out paper cup larynxes to his guitar collection, and I also brought a kazoo along to demonstrate how voicing changes airwaves. But it was the *other* form who gave us an amazing demo of one of their favourite assembly songs to demonstrate pitch changes – a really glorious moment.

Photo credit: Hotspur Primary School

Did it all work well?

We thought so! The children took part with enthusiasm, asking great questions about how the vocal cords seemed to change shape and about how speech sounds differ across languages. We taught the sessions on two different days, so we knew we’d had an impact on the first group, as the second already knew some of what we were going to talk about (plus they were well primed for the sweets). We will happily take playground chat as evidence of successful learning!

As for the teachers, they thought that increasing awareness of tongue movements could really help some of the children with language delay. Of course, speech and language therapists employ plenty of exercises that do just this, but we reckon there’s a benefit to be had by sharing all this information with children earlier and more generally, embedding it into phonics learning.

Want to know a bit more?

As you might imagine, we couldn’t do much more than that in a 45-minute session, and we didn’t even get onto manner of articulation****, a third factor in classifying sounds. We didn’t really demonstrate the International Phonetic Alphabet as a method for representing speech sounds, and we’d have loved to hand round kazoos to all (the teachers may have been less pleased with this). If you’re interested in thinking a bit more about place, manner and voicing and how we use these to describe sounds, here are some resources that might be useful (and spoiler: we’re in the process of trying to develop some that will complement traditional phonics programmes too!).

- seeingspeech.ac.uk – the IPA chart is organised by place, manner and voice, so have a play with the videos and audio recordings

- Dr Sean Pert’s website has a wealth of information on language sounds and development from a speech and language therapy POV, along with a resource to test your ability to determine place, manner and voice

Notes

*From lingua, Latin for ‘tongue’, came the 16th century coinage ‘linguist’, meaning “master of languages” or “one who uses their tongue freely”. ‘Linguistic’, meaning “pertaining to language(s)” was an early 19th century innovation from German linguistisch, fabulously described by the OED as “hardly justifiable etymologically [… but] has arisen because lingual suggests irrelevant associations.” The term ‘linguistics’ for the field of study followed in the mid 19th century, but only really took off (and overtook its main competitor, ‘philology’) in the late 1940s. All info in this note, apart from the Google Ngram, is taken from the wonderful resource etymonline.com: linguist, linguistic, linguistics.

**Maoam Joystixx were far and away the best sweet for this experiment, with Swizzles Matlow Drumsticks as a decent runner-up as a vegetarian/halal option. No, this isn’t an #Ad. Yes, there was an extensive testing period one afternoon ;).

***Yes, OK, context helps too. But sometimes that is absent, and sometimes terrible analogies happen too.

****This is to do with how the articulators (lips, tongue, teeth, etc.) relate to each other, mostly in terms of how close they are. For example, the initial sounds in both tap and sap are unvoiced and made by placing the tip of the tongue at the alveolar ridge, but where there is complete closure of the tongue against the alveolar ridge for /t/, it’s just close to the ridge for /s/, allowing air to hiss through that small gap.