This blog post is part reminisce, part information about children’s earliest language experience, and part reflection on an event I ran in November 2023 as part of the Being Human festival. If any of this sounds interesting to you, please read on…

My eldest’s first poem was composed shortly before he turned three.

Now, proud parent I may be, but let’s be clear – I’m not claiming that he pulled his mini IKEA chair up to a tiny bureau, called for his quill, and committed his thoughts to parchment with an inky flourish (in fact, now five years of age, Smidge is still largely a pen-refuser).

Rather, he had discovered the pleasure of pairing words like “dog” and “cot” as part of a developing awareness of assonance – vowels that are shared across words, even if their consonants differ.

From there, he started to exclaim over his breakfast – “Mummy! “Spoon” and “moon” rhyme!” We were then just a hop, skip and a jump from his first couplet, gleefully stitched together and bellowed as we puddle-jumped our way to the bus one autumn morning –

Cosy wosey,

Rosy nosy!

A very cheerful rendition of autumn from a fledgling poet wrapped up in fleece and mittens.

Smidge’s increasingly conscious play with vowels also reminded me of one of my odder teaching moments. I was in my fourth year teaching Child Language Acquisition at the University of Huddersfield. It was always one of my favourite courses to teach, with a different group each year of enthusiastic, thoughtful, funny final year students.

I started from the beginning, presenting some pretty incredible work showing how children in utero can perceive some vowel sounds and tell them apart about 10 weeks before they are due to be born.

The class started looking at me a little strangely. One or two even giggled.

Of course. I was standing (well, perching) in front of them, about 30 weeks pregnant. As I was passing on degree-level knowledge to my students, I was simultaneously passing on foundational knowledge about English intonation and vowels to Smidge there on the inside, invisible and yet very much present on the room with us. Largely silent, but very much listening in.

Smidge at about 32 weeks gestation, still listening.

Jump now to late 2023. Inspired by my academic knowledge and my experiences as a parent, I’m standing in front of a room full of preschoolers and their parents, at an event called I’ve designed with two colleagues, a linguist (the superb Dr Emma Nguyen) and a poet (the horribly talented Harry Man).

The audience includes nursery friends of Smidge. I ask the children when they learned their first sound. Quick as a flash, Friend-of-Smidge calls out, “Alphablocks!” A gorgeously guileless answer from someone becoming much more consciously aware of the world of sounds around him as he becomes immersed in primary school phonics schemes (on which more another time…)

Photo credit: Luke Waddington

I near blow Friend-of-Smidge’s mind when I tell him that he learned his first sounds from inside his mum’s tummy. But this is mostly just set up: for the rest of the hour with the preschoolers, my colleagues and I play on the children’s earliest linguistic experiences – distinguishing vowels – to create poetry with them. 1960s experimental French poetry, no less.

Univocalisms are poems written using just one of the five (orthographic) vowels – A, E, I, O or U. Of course, each of these letters can represent a range of different phonemes (tall, pan, saga, agar)*, and sometimes different orthographic vowels can represent the same phoneme (feet, mini)**. We also played very fast and loose (for linguists) by allowing Y in all cases. But we only had an hour to work with here, so we felt justified!

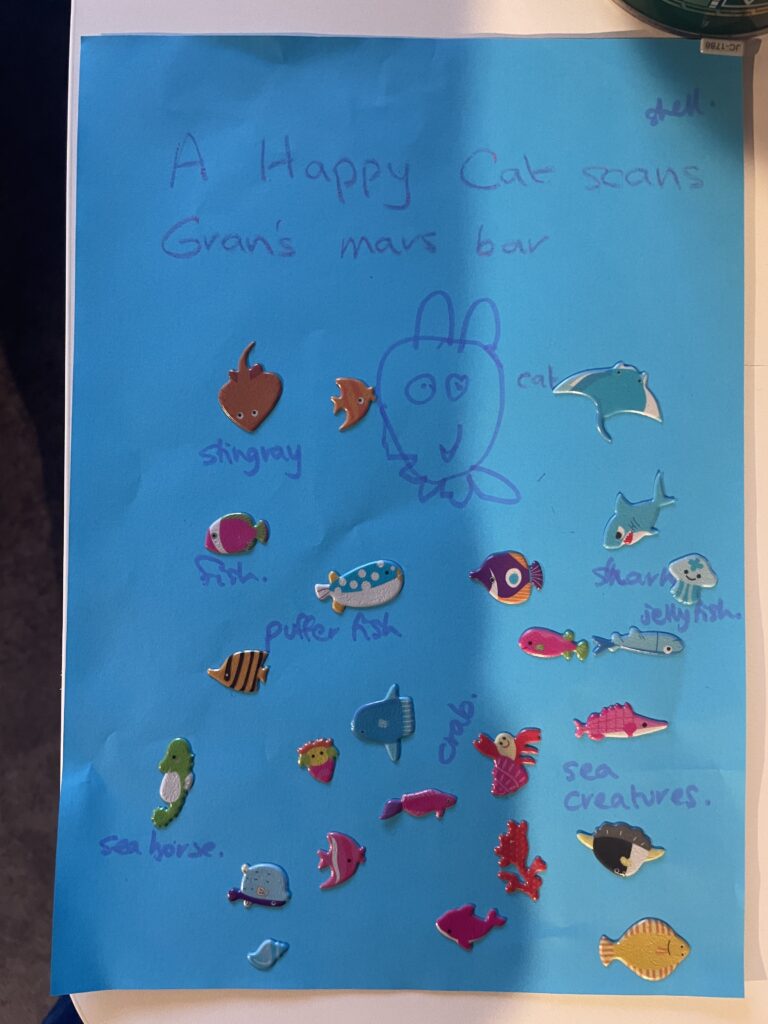

We provided some worksheets and some envelopes of words for each vowel and encouraged the children to come up with sentences consisting of two noun phrases (containing an adjective and a noun), linked by a verb – so introducing a little extra linguistic vocabulary along the way. The only other instruction was to go as crazy as possible – we wanted as many fancy prawns to scan Granny’s pants as possible!

And they did an amazing job! Our fantastic student assistant Lainie created a zine of their best efforts, which we sent around to all the participating families and you can view here (spot also my own effort, as well as poems by Emma, Harry and Lainie). Huge thanks to the AHRC and the Being Human Festival for funding our event. We now hope to take it around primary schools in the area to encourage slightly older children, around 5-7 years old, to keep playing with their languages and to sneak a bit of early linguistics into their consciousness too.

What did we learn from the event? That there’s a lot of mileage in just getting children to make funny sounds (even more so if funny faces are involved), that there are few things funnier than the idea of an eggy bee stretching smelly jelly (I mean, genius) and that we have so, so much more to learn about what children know, implicitly and explicitly, about language in the preschool years.

*t[ɔː]ll, p[æ]n, sag[ə], [eɪ]gar

**f[iː]t, min[i] – give or take a bit of lengthening of the vowel, indicated by “ː”