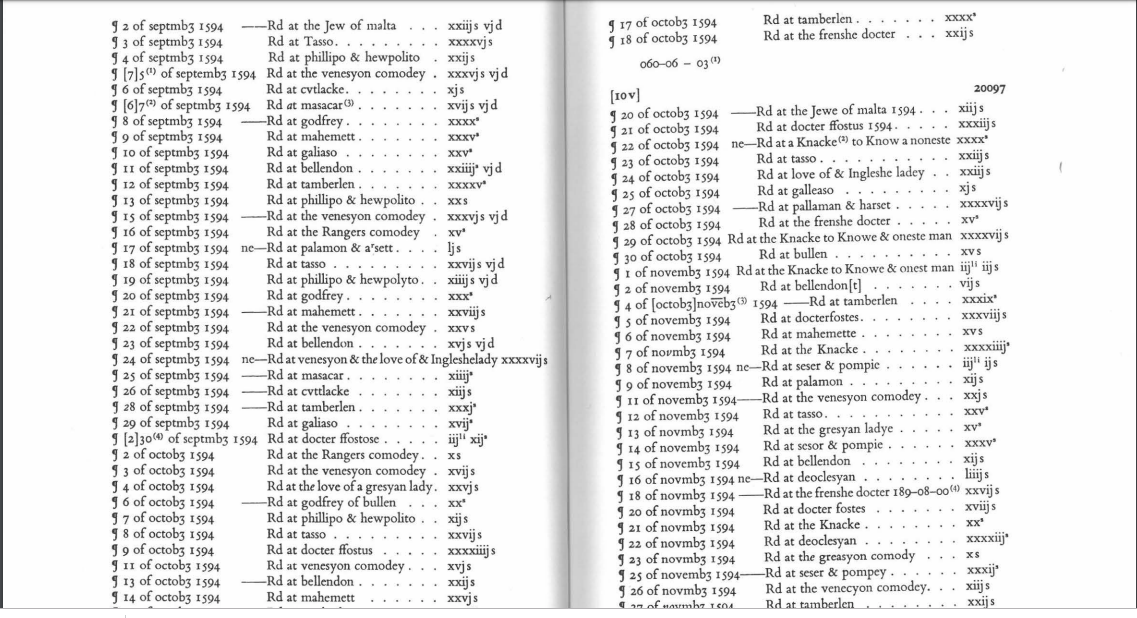

In regards to Shakespeare’s collaboration there are two key strands which can be focused on. Firstly is Shakespeare’s immediate and direct collaborator, The Chamberlain’s Men acting company which consists of 8-12 senior members and beneath these 2-4 apprentice boys. Not only does the acting troupe possess a financial hold over performances through shares but their role itself, by interpreting Shakespeare’s written word in their performances is open to be viewed as collaborative.

Beyond this though is the social network of playwrights and authors writing both at the same time as Shakespeare but also in the past. Some of Shakespeare’s main competitors and potentially collaborators included Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson and John Lyly.

Clare references how “Shakespeare’s plays are not separable from other plays in circulation” (Clare, 18), going on to suggest that writings should be viewed “on a circularity rather than linearity” spectrum as they can influence and affect one another at any point in time (18). Not only is this a concept supported by Seneca’s bee theory, which suggests within our works people should “sift whatever we have gathered from a varied course of reading” and apply it but can also be seen through both Shakespeare’s works and his competitors alike (Seneca 277, 278, 279).

There is a distinction between intertextuality and influence here though as Shakespeare responds with intertextuality while the example of his competitor is influenced.

Shakespeare, for example, responds to John Lyly’s Galatea by adopting its formula of a “non-naturalistic comed[y], with […] mythological and human characters” within A Midsummer Nights Dream (123). From their shared woodland setting to their inclusion of Gods within their plots there are clear parallels which can be drawn between the two texts, demonstrating one text’s shaping by another. Alternatively though texts can instead influence one another, with Shakespeare in this different instance acting as a source of inspiration for writers as John Webster includes Shakespeare in his preface to The White Devil 1612 printed by Nicholas Okes for Thomas Archer. Webster regards that “lastly (without wrong last to be named) the right happy and copious industry of M. Shake-speare, M. Decker,& M. Heywood, wishing what I write may be read by their light:” (Webster, Folger Shakespeare Library), demonstrating Shakespeare’s influence and his role as a source of inspiration but not his work being used intertextually. That is not to suggest that these are the only examples of this though as influence and intertextuality in a broad range of instances.

It appears that the key writers featured in Clare’s essays were potentially more prone to specialising in a specific genre – Marlowe focused a lot on tragedy, whilst Lyly and Jonson wrote mostly comedy.

Reference

Clare, Janet. Shakespeare’s Stage Traffic: Imitation, Borrowing and Competition in Renaissance Theatre (CUP, 2014) pp. 18

Seneca the younger, Epistles vol 2, transl. Gummere (Loeb: 1920) pp. 277-279

Webster, John. “The White Devil: John Webster refers to Shakespeare by name in his dedication (1612).” Folger Shakespeare Library, Shakespeare Documented, May 25th 2017, https://shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/exhibition/document/white-devil-john-webster-refers-shakespeare-name-his-dedication. Accessed 15 Oct. 2019

Abi Dickson, Ellie Simmonite, Soso Ayika, Sophie Hamilton, Raveena Mehta, Leanne Francis

Lords and Ladies, warlocks of this age of technological wonder, please take a moment from your busy lives and buzzing devices to consider the past. Once shrouded by the time manipulation legislation, the no deal Galaxy E-exit (Earth Exit) has allowed us to take control of our own spacetime. For the small price of £1bn we are allowing you the opportunity to travel back in time to renaissance England:

Lords and Ladies, warlocks of this age of technological wonder, please take a moment from your busy lives and buzzing devices to consider the past. Once shrouded by the time manipulation legislation, the no deal Galaxy E-exit (Earth Exit) has allowed us to take control of our own spacetime. For the small price of £1bn we are allowing you the opportunity to travel back in time to renaissance England: