‘A Lilliputian Miscellany’ now open to the public June – August 2017.

‘A Lilliputian Miscellany’ now open to the public June – August 2017.

Level 1, Philip Robinson Library, Newcastle University

Curated by Brian Alderson, ‘A Lilliputian Miscellany’ celebrates the gift of the Alderson Collection to Newcastle University and Seven Stories. Read more about the children’s book collection in the Vital North Partnership blog. It shows some of the less usual children’s books and manuscripts in his Collection and relate many of them to Brian’s career as writer, translator, and editor. What a commingling will be seen as the Brothers Grimm rub shoulders with Charles Kingsley, or a tribute is paid to those Northumbrian figures of Thomas Bewick illustrating Mother Goose’s Melody and Joseph Ritson with his Gammer Gurton’s Garland.

Brian Alderson is one of the pioneers of children’s literature studies in Britain and a distinguished author, reviewer, translator and collector. In 2016, Brian Alderson was awarded an honorary degree by Newcastle University, recognising his work on the history of children’s books. Find out more about Brian and his work on the Brian Alderson website, or view the items from Brian’s collection that have already been catalogued on Newcastle University’s Library Search.

Brian Alderson has written the text himself and some of the highlights from the exhibition are shown below, but there are many more wonders to see in the exhibition in the Philip Robinson Library. An accompanying exhibition catalogue is also available, which provides more detail about the items.

Boreman and Newbery

For well over a hundred years the eighteenth century bookseller John Newbery in St Paul’s Church-Yard has been the cynosure of the collecting fraternity. It was he who established a steady output of children’s books sufficient to prove to the trade that this could be a new and profitable line of business.

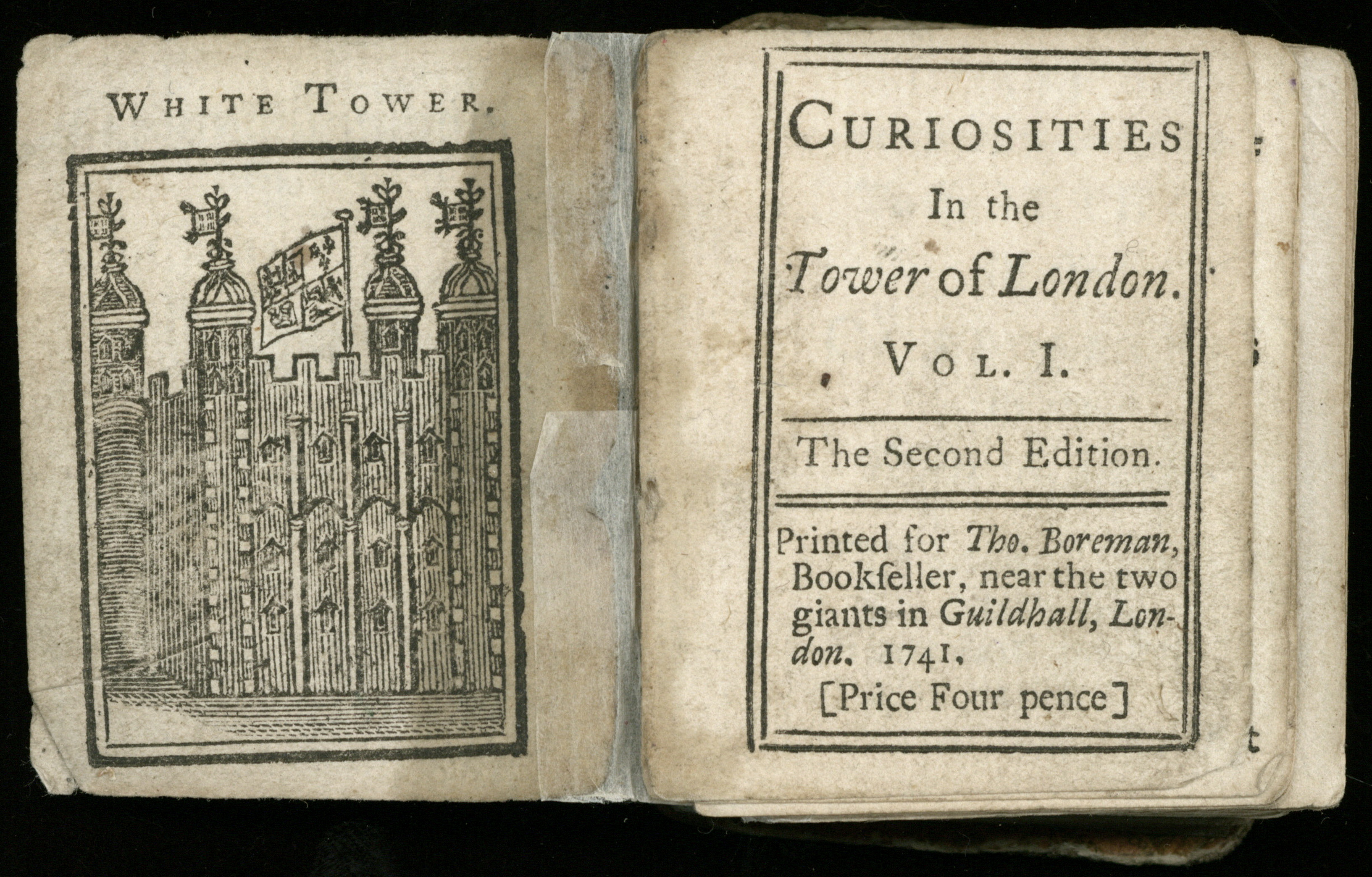

While Newbery’s most famous books are rare they are probably less so than his important predecessor, Thomas Boreman, who’s Gigantick Histories began to come out a year or two before any of Newbery’s books. I had never thought to own one of these tiny volumes which stand at the true beginnings of the regular children’s book trade, but Thomas Boreman’s Curiosities of the Tower of London, came to me through an extraordinarily lucky purchase from a bookseller’s catalogue at a price whose modesty I found unbelievable.

THOMAS BOREMAN

Curiosities of the Tower of London

1741

The prelims include Boreman’s celebrated rhymed puff on the theme that ‘Tom Thumb shall now be thrown away’ in favour of ‘something to please and form the mind’ which is followed by a 14-page list of ‘Subscribers to this Work’, reprinted from the first edition of the same year. The illustrations, barring one of the defeat of the Spanish Armada, are extremely attractive cuts of some of the animals housed in the Tower of London’s menagerie.

Anon

The Story of Goody Two Shoes

1940

One of the many series of miniature coloured booklets that were issued early in the Second World War for reading in air-raid shelters etc.

Nursery Rhymes

I first met Peter Opie round about 1967 when we were forming what was to become the Children’s Books History Society. Subsequently we went several times as a family to Westerfield House (now Mells House) when book treasures were revealed to me while the children enjoyed the historic toys that were demonstrated in the room that Peter and Iona Opie called ‘the Museum’.

With an Opie-inspired interest in the history of nursery-rhyme publishing, it led me to the following interesting editions appearing in the collection.

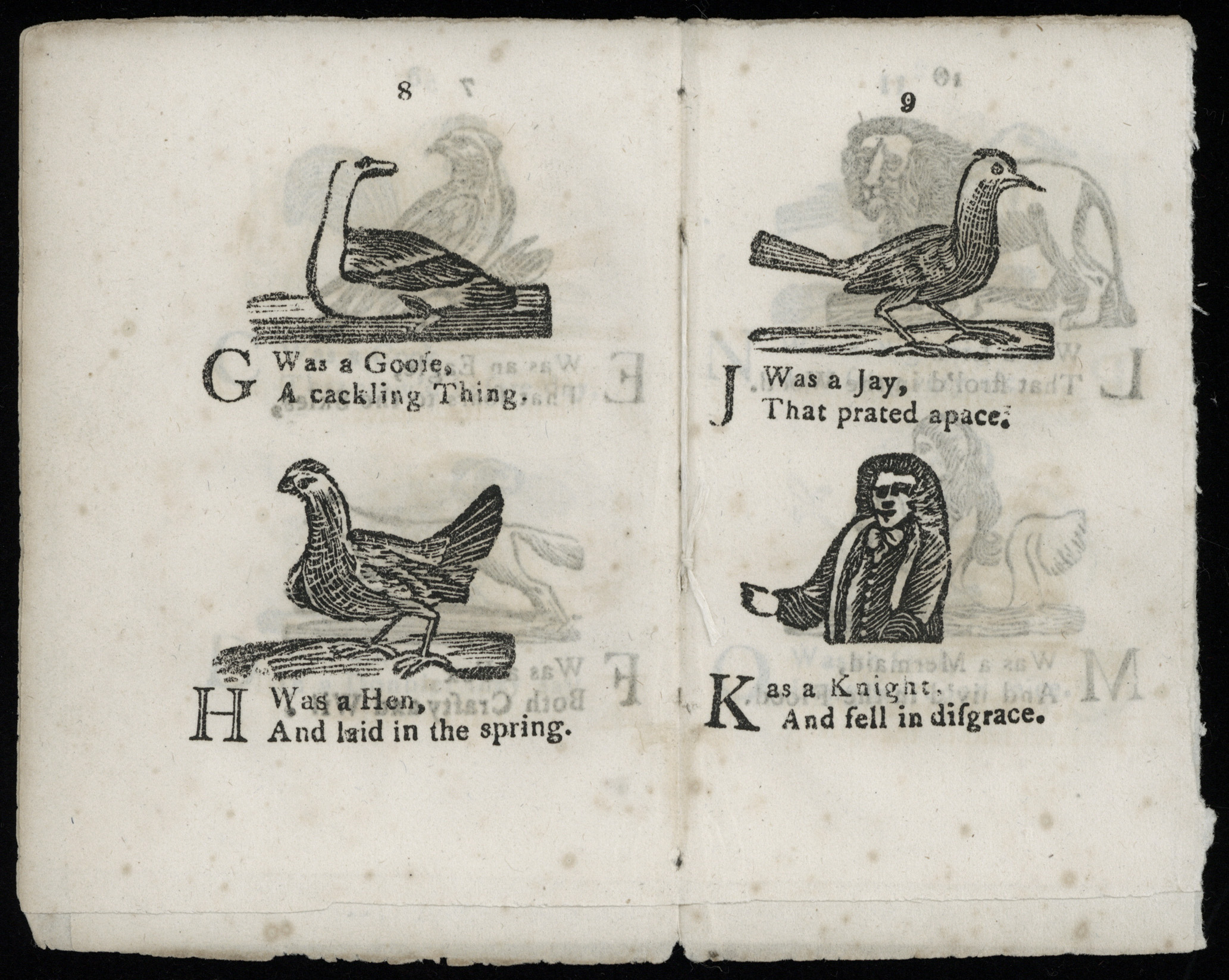

Tom Thumb’s Play-Thing, being a new and pleasant method to allure little ones into the first principles of learning; with cuts well adapted to each letter in the alphabet. As brought into easy verse for the instruction and amusement of children.

No date [ca. 1810]

The prodigious title belies the extreme simplicity of the two chapbooks, the first consisting simply of the two alphabets ‘A was an Archer’ and ‘A was an Ape’, the second a series of six couplets (‘The Sun shines bright, / The Moon gives light.’ etc.) followed, alas, by a 5-page catechism and a story on the rewards of learning to read which commends: ‘Robinson Crusoe and Goody Two Shoes which are sold, with many others, as well instructive as entertaining, in gold covers, embellished with a variety of pictures, at the same place as this…’ Although not including any rhymes from Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song-Book Volume II these chapbooks may well draw upon the contents of the lost first volume.

Mother Goose’s Melody; or, sonnets for the cradle. Containing the most celebrated songs and lullabies of the old British nurses. Embellished with many beautiful pictures.

No date (Watermarks 1809 and 1810)

It has been suggested that this important collection of 51 rhymes was first planned by John Newbery just before his death in 1767 but the first edition, perhaps from his papers, did not appear until 1780, published by his successor, Thomas Carnan, who added sixteen poems by ‘that sweet Songster… Master William Shakespeare’. The earliest surviving copy, a facsimile of which is exhibited alongside this book, was published soon after Carnan’s death in 1788 by his brief successor, Francis Power. He revised the production process, dropping Shakespeare and aligning the book to the new fashion for hand-coloured picture books in a square format.

Folk Tales

It was an interest in ballads, dating back to undergraduate days that encouraged my attention to the oral qualities in children’s literature and especially in the transmission of folk tales, which have no definitive text but are rooted in the told story. It seemed to me of primary importance to judge the printed forms of these old familiar narratives, either those native to an English, Scottish or Irish tradition or, especially, those translated from their original sources by the degree of their adherence to natural speech.

A fundamental influence on both theory and practice came when, in 1968, I was sent The English Fairy Tales edited by Joseph Jacobs.

ANDREW LANG, Brian Alderson illustrated by John Lawrence

The Blue Fairy Book

Joseph Jacobs was the inspiration for the editorial work that I undertook in ‘refurbishing’ this famous collection; I think too that he would have shared my misgivings as to its first editing which was largely the work of Mrs Lang and assorted friendly ladies. With Patrick Hardy’s (editor at Kestrel Books) encouragement, I attempted a wholesale revision (fully explained in my Preface and notes) in an attempt to bring the volume more closely towards the folk tradition at the root of ‘fairy tales’. At the same time, a decision was made to replace the (often very strong) illustrations by H. J. Ford with a contemporary illustrator and John Lawrence, who undertook the task, was asked to look at Ford’s work and attempt to replicate its notable position in ‘the black-and-white’ tradition (this occurred very successfully with later illustrators too).

Hans Christian Anderson

Where Hans Christian Andersen is concerned an entirely different critical regime is required for the (often unrecognised) reason that his canon of 156 stories is that of an independent author whose texts do not share the multivalency of those from folk tales. They are crafted works of literature (which all too often suffer from abridgment or adaptation) and – importantly – many of them draw directly upon Andersen’s own voice as storyteller.

The items give merely a glimpse of the challenge and enjoyment of the chase of collecting Hans Christian Andersen’s stories.

HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSON [SIC]

Wonderful Stories for Children

1846

Published for Christmas 1845, this first English translation of the Eventir advertises ten stories on the contents page. Thus, right at the beginning, we find liberties taken with poor old Andersen’s texts. Leaving aside the misspelling of his name on the title-page, we also find a story called ‘A Night in the Kitchen’, which proves to be a passage excerpted from ‘The Flying Trunk’, one of Andersen’s funniest stories. At least it is taken from the Danish, unlike most of its immediate successors and it is perhaps understandable that, being the first to attempt the job, Howitt has not the ear to catch the fluency of the author’s unusual conversational lightness.

(18) G[EORGE] N[ICOL]

The Ugly Duck of Hans Christian Andersen

1851

A little book with a complex parentage. Its author was the brother of its publisher (who was Bookseller to the Queen) and in 1837 he published a versification of Southey’s The Three Bears. In 1840 that was jokingly joined by a versification of the Grimms’ Wolf and the Seven Little Kids (probably based direct on the German version) and in 1841 the two stories were joined with a third on ‘The Vizier and the Woodman’. We do not know why it took George so long to catch up with Hans Christian Anderson, for The Ugly Duckling was among the favourites of the 1846 tranche of translations.

Verses

It could be argued that if nobody had ever written poetry to be read primarily by children the children would not be very much the poorer. The mass of anonymous popular versifying enjoyed by everyone, which would include nursery rhymes, makes a foundation for the child’s love of rhythmic speech and, as many an anthology will prove, there is a mass of poetry written primarily for adults which can be equally enjoyed by the young. A Blake, a Lear, a Stevenson, and others can justify the genre and this section points up some of its rarer or less usual manifestations.

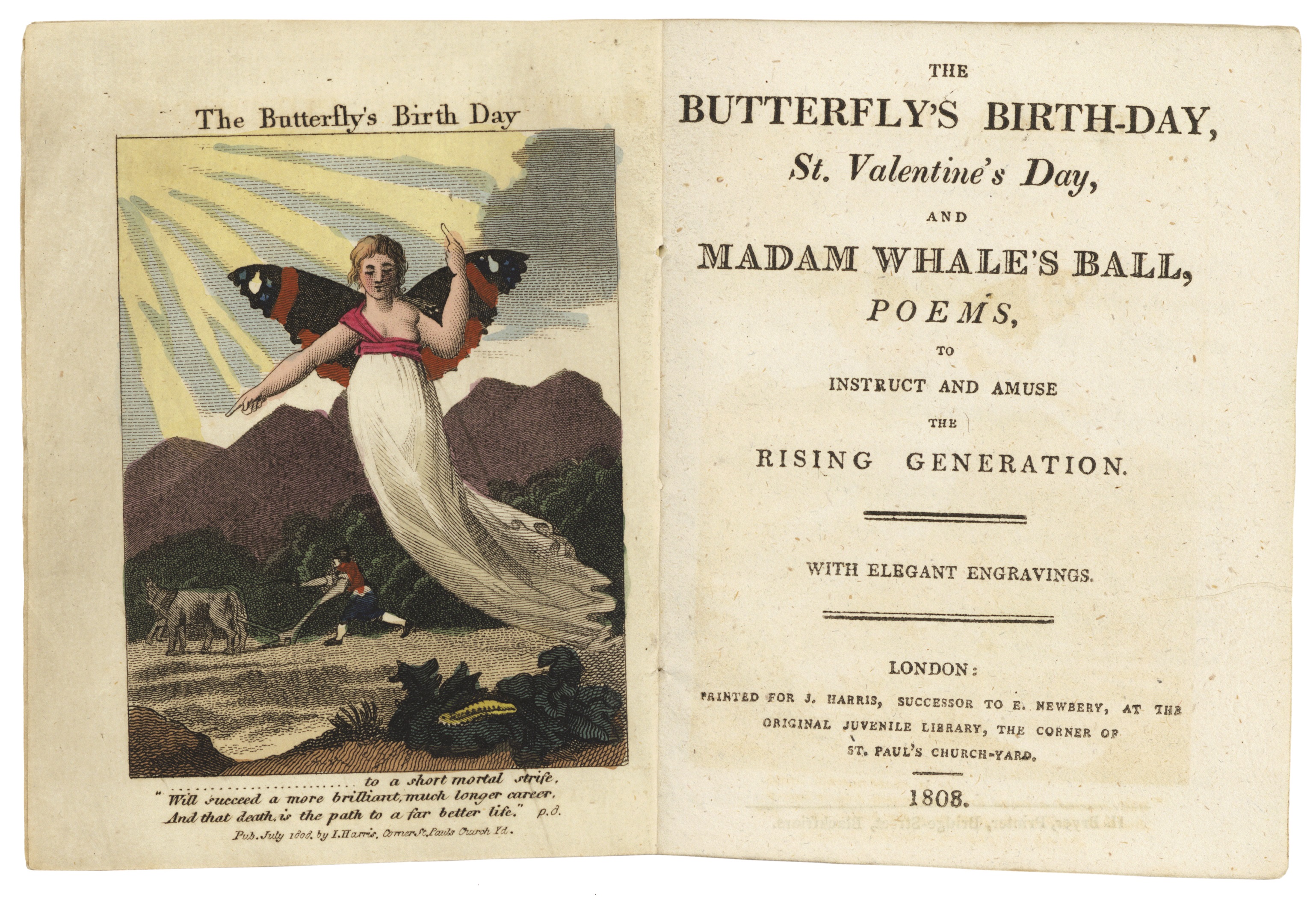

The Butterfly’s Birth-Day, St. Valentine’s Day. And Madam Whale’s Ball, poems to amuse and instruct the rising generation.

1808

Three sets of verses, the first signed ‘A. D. M.’, preoccupied, as with the founding party-poem, with crews of animals attending first the butterfly’s birth, bursting out of its chrysalis, second pairs of creatures on a Valentine’s parade and third various sea creatures aiming to emulate the (earlier published) ‘elephant’s rout’. Mechanical stuff, although it is good to know that some little fellows got to the birthday:

From Chester and Stilton, by waggons and stages,

Trav’ling snug in old cheeses, by land and by sea,

Congregations of Jumpers and Mites of all ages,

Fast arrived at the spot the new marvel to see.

Title page from ‘The Butterfly’s Birth-Day, St. Valentine’s Day. And Madam Whale’s Ball, poems to amuse and instruct the rising generation’

EDWARD LEAR

A Book of Nonsense

1862

I have loved Lear from childhood on (as who could not?). This third edition seems to be rarer than one might expect (the collector William B. Osgood Field only knew it through owning Lear’s proof copy!) and it is important as including 46 hitherto unpublished limericks and being illustrated with wood engravings rather than the previously hand-drawn lithographs.

The collection holds most of the later nineteenth century editions and many twentieth-century ones whose re-illustration, with the exception of the work of Edward Gorey and John Vernon Lord, are deplorable.

Humphrey Milford, OUP and The Water Babies

On the day that I bought H.R.Millar’s The Dreamland Express it was borne in upon me that more was going on at the London office of Oxford University Press (OUP) than I had bargained for. I began to look out more regularly for books with the Henry Frowde or Humphrey Milford imprints, conjoined usually with Oxford University Press, in catalogues and at book fairs.

The Little Old Woman of X

No date [?1916]

Humphrey Milford (later Sir Humphrey) took over from Henry Frowde at the London office of Oxford University Press in 1916 and I suspect that string-bound volumes, sometimes in little slip-cases, may have been in production before that time.

Another interest of mine is in Charles Kingsley’s famous but barmy story, which led me to collect variant editions of The Water Babies which now number about sixty. My mother read it to me as a child and I held in my memory recollections of Samber’s illustrations from the most frequently reprinted edition of the story and my aim in forming the collection was (and still is) a desire to compile a critical account of the failure of almost every illustrator to cope with the demands of Kingsley’s text.

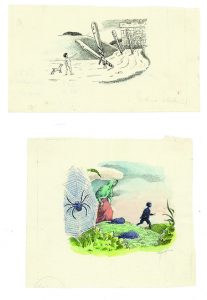

CHARLES KINGSLEY

The Water-Babies; a fairy tale for a land-baby

1863

Below are 2 holograph fine line drawings by Harold Jones for pages 33 and 107 of the edition edited by Kathleen Lines (1961). The first drawing coloured by Harold Jones for a selling exhibition, where I bought them. The quality of Jones’s drawing is ruined by both the printing and the paper of the published edition.

WALT DISNEY

The Water Babies [2-colour vignette]

No date [ca. 1936]

An (expensive) catastrophe, being not only one of the ugliest books in my collection but one which has nothing to do with Charles Kingsley and his story. Still – it looks nowadays to be quite a scarce volume.