(London: George Newnes, 1937)

Held in Laura Gillott’s personal collection

An exhibition curated by Laura Gillott

Introduction

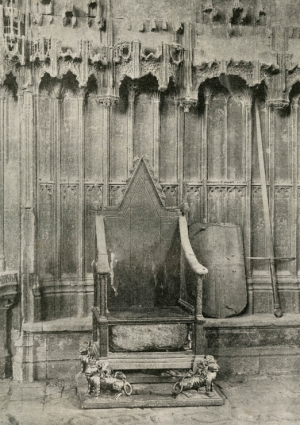

King Edward’s Chair, or, The Coronation Chair, is the throne on which the British monarch sits during their coronation. It was commissioned in 1296 by King Edward I to contain the coronation stone of Scotland, the Stone of Scone, which he had captured from the Scots. The chair was named after Edward the Confessor and was kept in his chapel at Westminster Abbey. Since 1308, with only a few exceptions, anointed sovereigns of England have been seated in this chair at the moment of their coronation. It is the coveted ‘throne’: fought for, and sought by, so many claimants over the years. To sit upon it was to be made monarch.

Throughout history there have been a huge number of claimants to the English throne. Some have posed more serious threats than others and some have even successfully usurped reigning monarchs. Thus, over the centuries, those in power have kept a close eye on their rivals and potential heirs to the throne.

Female claimants, whilst rarely considered as posing as significant a threat as their male counterparts, have arisen over the years. Queen Elizabeth I was herself accused of trying to overthrow Queen Mary I in 1554 and, when Elizabeth was Queen, she was so fearful that Mary, Queen of Scots planned to usurp her, that she eventually had her executed in 1587.

Women have been watched especially with regard to their choice of husband in fear that a wisely-chosen matrimonial union could have strengthened their claims to the throne. Although some claimants never showed any desire to become Queens, their very existence was considered threatening.

This exhibition looks at five women throughout history who came close to the English throne but whom, through war, death, imprisonment or bad luck, never became crowned as Queen. Had any of these women ascended to the throne English history could have been quite different and the modern royal family unrecognisable …

Empress Matilda (1102-1167)

Matilda of England was born in 1102. Matilda and her younger brother were the only children of King Henry I and Matilda of Scotland to survive to adulthood. The death of her brother, in 1120, made Matilda the last heir from the paternal line of her grandfather, William the Conqueror.

At twelve years old, Matilda was married to Henry V, the Holy Roman Emperor. After his death she returned to England and, in 1128, married Geoffrey of Anjou with whom she had three sons. Before Matilda’s father died in 1135 there were several contenders for the throne: Robert of Gloucester (the illegitimate son of Henry I); Stephen of Blois (Matilda’s cousin); Stephen’s older brother, Theobald; and Matilda (Henry’s only surviving legitimate child). Henry named Matilda as his heir and made the barons of England swear allegiance to her. Stephen was the first to do so but, when Henry died, he seized the throne, claiming that Henry had changed his mind on his deathbed. Stephen gained the support of the majority of the nobles as well as that of the Pope and his early reign was peaceful. Matilda then began military campaigns to re-claim her birthright.

(Rare Books, RB942.81 RAI)

Matilda’s half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, campaigned for her in England and she invaded in 1139. In 1141, her forces defeated and captured Stephen at the Battle of Lincoln. He was effectively deposed and she briefly ruled. Matilda went by the title ‘Lady of the English’ and planned to become Queen. She lost support when she refused to reduce taxes and the citizens of London re-started the civil war.

Stephen was freed in exchange for the captured Robert of Gloucester and, a year later, the tables were turned when Matilda was besieged at Oxford. She escaped by fleeing across the snow in a white cape and crossing the frozen River Thames. She also later escaped Devizes in a similar manner, by disguising herself as a corpse and being carried out.

[White (Robert) Collection, W942 HEN]

By 1148, after many failed attempts, Matilda accepted that she would never be Queen. Her eldest son, Henry, took up her cause and repeatedly invaded England. This led to the Treaty of Wallingford in 1153, in which Stephen agreed to name Henry as his heir. Matilda died in 1167 and is buried in Rouen Cathedral, where her grave is marked by the epitaph below:

The Ladies Catherine (1540-1568) and Mary Grey (1545-1578)

When King Edward VII lay dying, he nominated his cousin, Lady Jane Grey, as his successor to prevent his catholic sister, Mary, becoming queen. Jane ruled for nine days in July 1553 before Queen Mary I seized the throne that was rightfully hers according to Henry VIII’s will. Jane was imprisoned in the Tower of London and executed, along with her father and husband in 1554. The ladies Catherine and Mary Grey were the younger sisters of Lady Jane Grey and cousins to Queen Elizabeth I. After Jane’s execution they both had claims to the throne as granddaughters of Mary Tudor, the younger sister of King Henry VIII. (Their parents were Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk and Lady Frances Brandon.) Neither Catherine nor Mary were as religious as the fervently Protestant Jane and this probably saved them from becoming the focus of Protestant plots whilst Mary I was on the throne.

Lady Catherine Grey was born in 1540. She was married to Henry Herbert, in 1553 (on the same day her sister Jane married Guilford Dudley). When Elizabeth I came to the throne, in November 1558, Catherine’s availability as a possible heir came to the fore. At one point the Queen seemed to be warming to Catherine and it was rumoured that she was considering adopting her. As Catherine was a possible heir to the throne, Elizabeth had to consider a suitable marriage for her. The best match would have been one that would not threaten her reign, but could bring some political advantages to England if Catherine were indeed to succeed her. A union between Catherine and the Earl of Arran (a young nobleman with a strong claim to the Scottish throne) was envisaged.

In December 1560, Catherine secretly married Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford. Not having the Queen’s official permission to wed proved disastrous. Elizabeth had decided to send Edward on an educational tour of Europe. Catherine, who had fallen pregnant before Edward left, managed to conceal the marriage from everyone. However, in her eighth month of pregnancy she knew she would have to ask someone to plead for her with the Queen. She first confided in Bess of Hardwick, who was frightened about the consequences of knowing such a secret and refused to listen. Catherine then secretly visited Lord Robert Dudley, in his bedroom in the middle of the night and told him her story, but the next day he reported everything to Elizabeth. Elizabeth was furious that her cousin had married without her permission and thus thwarted plans for her to marry the Earl of Arran.

Used with kind permission of the Duke of Northumberland.

The unmarried Elizabeth feared that Catherine would give birth to a son and start a rebellion. Thus Catherine was imprisoned in the Tower of London, where Edward joined her on his return to England. The Lieutenant of the Tower permitted husband and wife to secretly visit one another and, as a result, they had two sons: Edward Seymour, Lord Beauchamp, born in 1561 and Thomas Seymour, born in 1563. In 1562 their marriage was declared invalid and their sons illegitimate. After the birth of their second child, the Queen ordered their permanent separation. Catherine was moved from one location to another under house arrest, eventually ending up at Cockfield Hall in Yoxford, Suffolk. There, she died in 1568, at the age of twenty seven, from consumption.

Lady Mary Grey was born in 1545. She was reportedly slightly deformed and was described by her contemporaries as the smallest person at court. Like her sister Catherine, Mary angered Queen Elizabeth I by marrying without royal consent. Her marriage to Thomas Keyes, the Sergeant Porter, in 1563 resulted, two years later, in her imprisonment in the Tower of London. (The marriage had surprised many since Keyes was an unusually large man whose height contrasted with that of the tiny Mary.) It is possible Mary thought that by marrying someone of such lowly rank, Elizabeth would see her as no threat.

When Catherine died, Mary was brought to prominence as the last surviving grandchild of Mary Tudor. Since Catherine’s children were considered to be illegitimate, some people regarded Mary as heiress presumptive to the English throne. She remained under house arrest until 1572 and was permitted to attend Court occasionally. In spite of the intrigue surrounding her, it does not appear that Mary ever made a serious claim to the throne. Rather, it seems her life was ruined by her royal blood. She died childless and in some poverty, in 1578, at the age of thirty three.

Lady Arbella Stuart (1575-1615)

Lady Arbella Stuart (sometimes spelled Arabella) was born in 1575 and was considered a possible successor to Queen Elizabeth I. The only child of Charles Stuart, 1st Earl of Lennox, and Elizabeth Cavendish, Arbella was a direct descendant of King Henry VII. Through the paternal line, she was the great-granddaughter of Henry VIII’s sister. Both Arbella’s parents died before she was seven and she was raised by her grandmother, Bess of Hardwick.

(Durham: George Andrews, 1852)

[Rare Books, RB942.81 RAI]

Queen Elizabeth I came to the throne in 1558. As a woman, a Protestant, and having been declared a bastard after the execution of her mother, Anne Boleyn, in 1536, there were many who felt her claim to the throne was weak and as a result she always felt insecure and at risk from rebellions. Although Arbella’s claim to the throne was even weaker, Elizabeth feared her as she did all potential rivals, and kept a close eye on her throughout her life. It is likely that she preferred the idea of Arbella succeeding her rather than being succeeded by her Catholic cousin Mary, Queen of Scots. However, towards the end of her reign her close advisor, William Cecil, convinced her that Mary’s son, James VI of Scotland, who had been raised as a Protestant, should be her successor. There is no evidence that Arbella ever challenged this.

Towards the end of Elizabeth’s reign, there were reports that Arbella intended to secretly marry Edward Seymour. Arbella denied having any intention of marrying without the Queen’s permission. She was interviewed about her plans in the Long Gallery of Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire, in 1603.

Reference: 67944. ©NTPL/Andreas von Einsiedel.

Used with kind permission of Nikita Hooper, Picture Researcher, the National Trust Photo Library

– Room view of the whole of the Long Gallery at Hardwick Hall with the Gideon tapestries on the left. It measures to 162 feet long and 26 feet high. The Hardwick gallery is the largest of surviving Elizabethan long galleries.

Arbella found herself in trouble again when King James VI of Scotland ascended to the English throne and a plot was devised to overthrow him and replace him with Arbella. The main plot was devised by Arbella’s cousin, Lord Cobham, and Sir Walter Raleigh was among those involved. However, when Arbella was invited to participate by agreeing to it in writing, she reported the plan to James, thus escaping possible imprisonment herself.

In 1610, Arbella secretly married William Seymour, Lord Beauchamp, who later succeeded as 2nd Duke of Somerset. William Seymour also had royal blood as the grandson of Lady Catherine Grey. For marrying without royal permission, King James imprisoned them: Arbella in the custody of Sir Thomas Perry and Seymour in the Tower of London. The couple had some liberty within their prisons and were able to plan their escape.

In June 1611, Arbella dressed as a man and escaped to Kent. A proclamation issued on King James’ behalf stated that they had committed “great and heinous offences” and called upon all persons not to “receive, harbour or assist them in their passage” but to try and apprehend them and hold them in custody. However, it also stated that their intent was to “transport themselves into foreigne parts“. Thus, James must have known that Arbella posed no real threat to his throne and simply wished to escape to be with her husband. William did not arrive at the meeting place and so Arbella set sail for France without him. He had, however, escaped and was on the next ship to Flanders. By this time the alarm had been raised and ships sent after them. Arbella’s boat was within sight of Calais when she insisted upon stopping and waiting for William. This fatal pause allowed her captors to catch up to her and she was forced to surrender whilst, unbeknownst to her, William escaped. Arbella was returned to England and imprisoned in the Tower of London.

When Arbella fell ill in the tower in 1614, it was suspected she was faking illness either in order to escape or to gain sympathy. However, she refused both food and medical attention and was said by some to be delusional towards the end, believing William was coming to rescue her. When she eventually died in 1615 a post-mortem had to be carried out to rule out poisoning. It found that she had died slowly of starvation caused by her own negligence. It has been suggested that Arbella had porphyria, the disease George III and Mary, Queen of Scots are believed to have suffered from. This would explain both her physical and mental symptoms: porphyria can cause abdominal pain, vomiting, seizures and paranoia. She never saw her husband again and is buried in Westminster Abbey.

Princess Charlotte (1796-1817)

Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales was born in 1796. She was the only child of George, Prince of Wales (later King George IV) and Caroline of Brunswick. As the only legitimate grandchild of George III, she would have become Queen if she hadn’t died in childbirth in 1817, at the age of twenty one.

Charlotte’s parents disliked each other and separated soon after Charlotte’s birth. Prince George left Charlotte’s care to governesses and allowed her only limited contact with her mother. As Charlotte grew to adulthood, her father pressured her to marry William, Hereditary Prince of Orange, but after initially accepting him, Charlotte soon broke off the match. This caused much upset between her and her father, including him placing her under house arrest for several months. He finally permitted her to marry Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld.

The wedding took place in 1816 and huge crowds attended. It is believed that Charlotte suffered two miscarriages in quick succession after the wedding but, by early 1817, she was pregnant again and it seemed to be progressing well. Her pregnancy was the subject of much public interest, with people placing bets on the sex of the child. Charlotte’s contractions began on 3rd November, but the labour lasted for two days and she eventually gave birth to a stillborn boy on 5th November. Charlotte took the news calmly, stating it was the will of God. She seemed to be recovering but not long after the birth she began bleeding heavily and died soon afterwards.

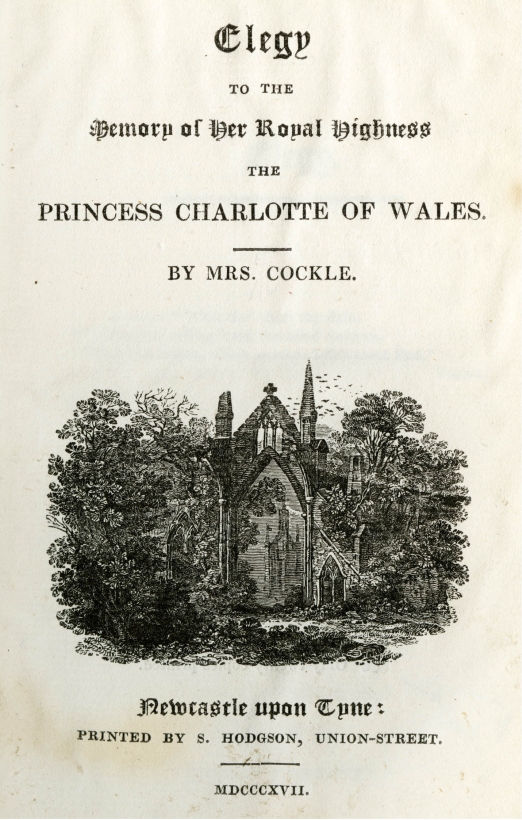

After Charlotte’s death, there was a huge outpouring of public grief and the whole country went into deep mourning. Linen-drapers reportedly ran out of black cloth and the country shut down almost entirely for two weeks, including the banks and courts. With the loss of his only heir, Prince George was inconsolable and unable to attend Charlotte’s funeral and Princess Caroline fainted in shock when she heard the news. However, it was Charlotte’s husband of just over a year who felt the greatest loss – he was said to be utterly devastated at the deaths of both his wife and son. Many elegies and poems were written about Charlotte, lamenting the loss of the heir to the throne and hope for the future.

[Clarke (Edwin) Local Collection, Clarke 1508(1)]

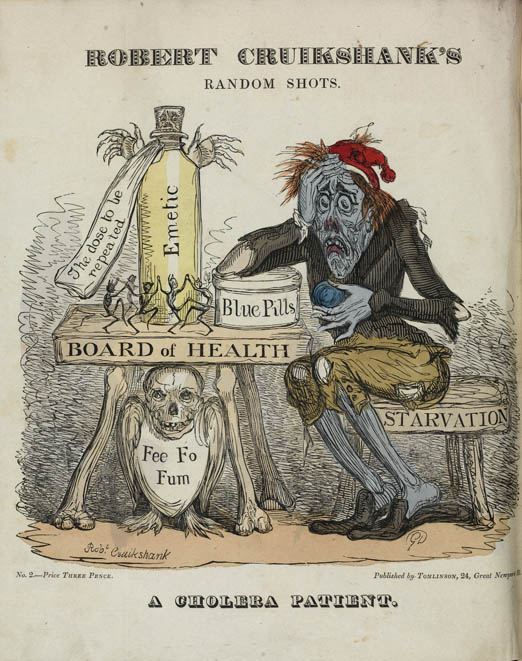

It wasn’t long before people looked for someone to blame for the tragedy. Although the post-mortem was inconclusive, many blamed Charlotte’s physician, Sir Richard Croft, and three months after her death, he killed himself. This led to significant changes in obstetric practice, with intervention in long labour becoming more commonplace and acceptable.

Princess Charlotte was buried, with her son at her feet, in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, on 19th November 1817. A monument was erected, by public subscription, at her tomb. People lined the streets along the funeral route from Claremont to Windsor to pay their respects to her. The mass public mourning is comparable with the outpouring of grief witnessed when Princess Diana died in 1997. With a mad king on the throne and an unpopular Prince of Wales, many had looked forward to Charlotte’s ascension to the throne and the new uncertainty about the succession accentuated the sense of grief felt by the British public.

What if they had been Queen?

Empress Matilda

As her son, Henry, acceded to the throne after Stephen, Matilda’s being Queen wouldn’t have changed the succession. However, if she, as a woman, had become a reigning monarch in the Twelfth Century, then it is possible that we may have seen another queen before Mary I in 1553. Also, if Matilda had been a successful queen then perhaps future kings, such as Henry VIII, would have been less concerned with the need to provide a male heir to the throne.

Lady Catherine and Lady Mary Grey

Although there was a good chance that either Catherine or Mary would become Queen, neither of them aspired to the throne and after the failed attempt to make their sister, Jane, Queen they could not count on a great deal of support from nobles who had no desire to lose their heads. Furthermore, neither of them was deeply Protestant, like Jane, and therefore they weren’t a viable alternative to the Catholic Mary I. As it turned out, neither of them lived long lives and it is likely that even if they had ruled, the reign would have been brief and relatively insignificant.

Arbella Stuart

It is difficult to say whether or not Arbella desired to be Queen. On one hand she never made any attempt to seize the throne but she had been raised as royalty and her romantic assignations suggest ambition. Even if she had been named as Elizabeth’s heir, James would almost certainly have tried to claim the throne himself and, as a man and King already, would have garnered considerable support. If James had died young, his son, Charles would have eventually tried to take the throne. As her claim wasn’t as strong as theirs, it would have made for a very unsettled reign for Arbella.

Princess Charlotte

Charlotte’s death left the king without any legitimate grandchildren and his other sons were urged to marry. George III’s fourth son, Prince Edward, dismissed his mistress and proposed to Leopold’s sister, Victoria. Their daughter, Princess Victoria of Kent, born in 1819, became heir and then Queen. Her uncle Leopold helped arrange her marriage to his nephew, Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. If Charlotte had not died then Victoria may never even have been born, and our current royal family would be descended from Charlotte instead.

Bibliography

Ainsworth, W.H. The Tower of London, with illustrations by George Cruikshank

(London: Richard Bentley, 1840)

An account of the interment of her Royal Highness the Princess Charlotte, inSt. George’s Chapel, Windsor, on Wednesday, Nov. 19, 1817

(Newcastle upon Tyne: Printed for J.S., 1817)

Chalmers, G. The life of Mary, Queen of Scots

(London: Printed for J. Murray, 1818)

Chibnall, M. The Empress Matilda: queen consort, queen mother, and lady ofthe English

(Oxford: Blackwell, 1991)

Cockle, Mrs. Elegy to the memory of Her Royal Highness the Princess Charlotte of Wales

(Newcastle upon Tyne: S. Hodgson, 1817)

A Complete history of England: with the lives of all the kings and queensthereof… 3 vols.

(London: Printed for B. Aylmer [etc.], 1706)

Davis, R.H.C. King Stephen, 1135-1154

(London: Longman, 1990)

De Lisle, L. The sisters who would be queen: the tragedy of Mary, Katherine and Lady Jane Grey

(London: Harper P., 2009)

Forester, T. (ed.) The chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon: comprising the historyof England, from the invasion of Julius Caesar to the accession of Henry II. Also, The acts of Stephen, King of England and Duke of Normandy

(London: H.G. Bohn, 1853)

Gardiner, J. (ed.) The history today who’s who in British History

(London: Collins & Brown; Cima Books, 2000)

Grey, Lady J. The life, death and actions of the most chast, learned, andreligious lady, the Lady Iane Gray, daughter to the Duke of Suffolke: containing foure principall discourses written with her owne hands . . .

(London: Printed by G. Eld. For John Wright, 1615) EEBO (13/05/2011)

Gristwood, S. Arbella: England’s lost queen

(London: Bantam Books, 2003)

Holmes, R.R. Queen Victoria

(London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1901)

James I, Sovereign. [Proclamation.] By the King whereas wee are giuen tovnderstand, that the Lady Arbella [sic] and William Seymour … being for diuers great and hainous offenses, committed, the one to our tower of London, and the other to a speciall guard

(Imprinted at London: By Robert Barker, Printer to the Kings most Excellent Maiestie, Anno Dom. 1611) EEBO (13/05/2011)

Leslie, S. George the Fourth

(London: Ernest Benn, 1926)

Priestley, J.B. The prince of pleasure and his regency, 1811-20

(London: Heinemann, 1969)

Raine, J. A brief historical account of the Episcopal castle, or palace, ofAuckland

(Durham: George Andrews, 1852)

Shanks, E. The coronation of their most gracious majesties King George VI and Queen Elizabeth

(London: George Newnes, 1937)

Stuart, D.M. Daughter of England

(London: Macmillan, 1952)

Woodward, G.W.O. King Henry VIII

(London: Pitkin Pictorials, 1969)