An archive recently gifted to Special Collections from the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology offers a unique insight into this pioneering, sub polar expedition through transcripts of the radio communications between the ground team and the US Air Force. Among its participants was Hal Lister; a Geography lecturer at Newcastle University who served as a Glaciologist here and later on the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1955 – 1958), led by Vivian Fuch and supported by Sir Edmund Hilary.

The archive is nationally significant and documents the first large-scale British expedition and scientific exploration of the Greenland Ice Sheet. The archive captures significant events, achievements (e.g. the crossing of the ice sheet), and logistical challenges of undertaking such a large-scale expedition at a time when polar logistics were inherently difficult and dangerous. It represents a unique day-to-day’ record of a large-scale, but little-documented, Cold-War era British scientific exploration.

The purpose of this expedition, led by Commander James Simpson, was primarily scientific studies in glaciology, meteorology, geology and physiology, but also so the armed services could gain experience working in polar conditions.

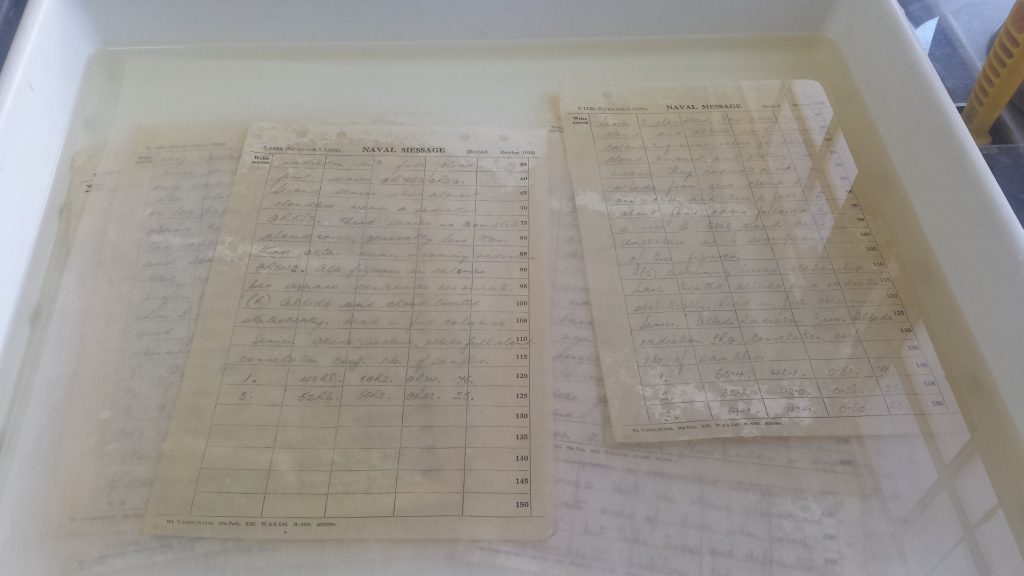

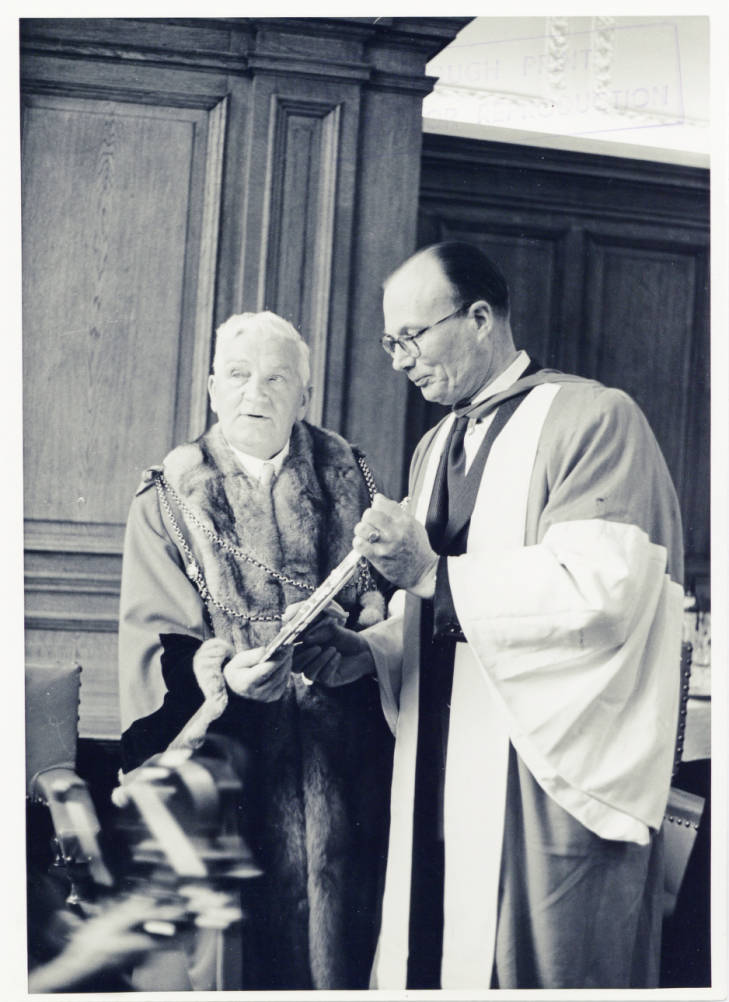

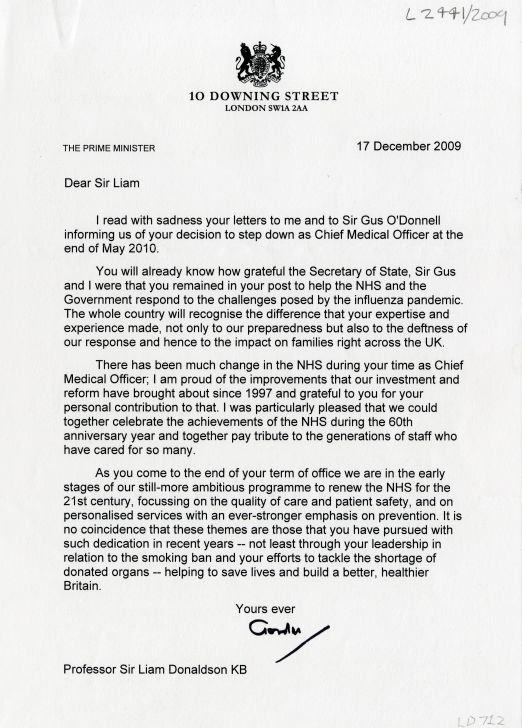

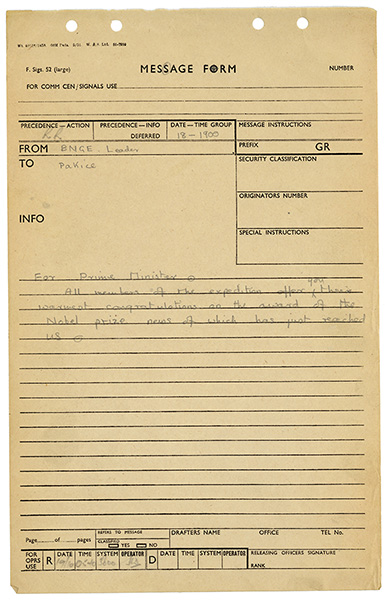

In his second spell as Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill was very proud to be Vice-Patron of the expedition and offered his best wishes to the team before their departure in July 1952 from Deptford (right). Among the pencil-written messages conveying both scientific messages, details on supplies, and jokes between the expedition and support team, is this particular message from Simpson. In it, he offers congratulations to Churchill on receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1953, where he beat writers such as Ernest Hemingway for his numerous historical accounts of both World Wars.

Greenland was a successful venture and amongst the team’s achievements included two pioneering ascents in the Barth Mountains and Dronning Louise Land. Sadly, there was one fatality, in 1953 when Captain H. A Jensen of the Danish Army fell to his death. The entire team were awarded the Polar Medal in November 1954.

Conservation at work

The documents arrived at Newcastle University Special Collections and Archives and a bundle of papers.

We then sent this archive off to Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums to work their conservation magic, to flatten and preserve the papers. Here’s the conservation in progress…