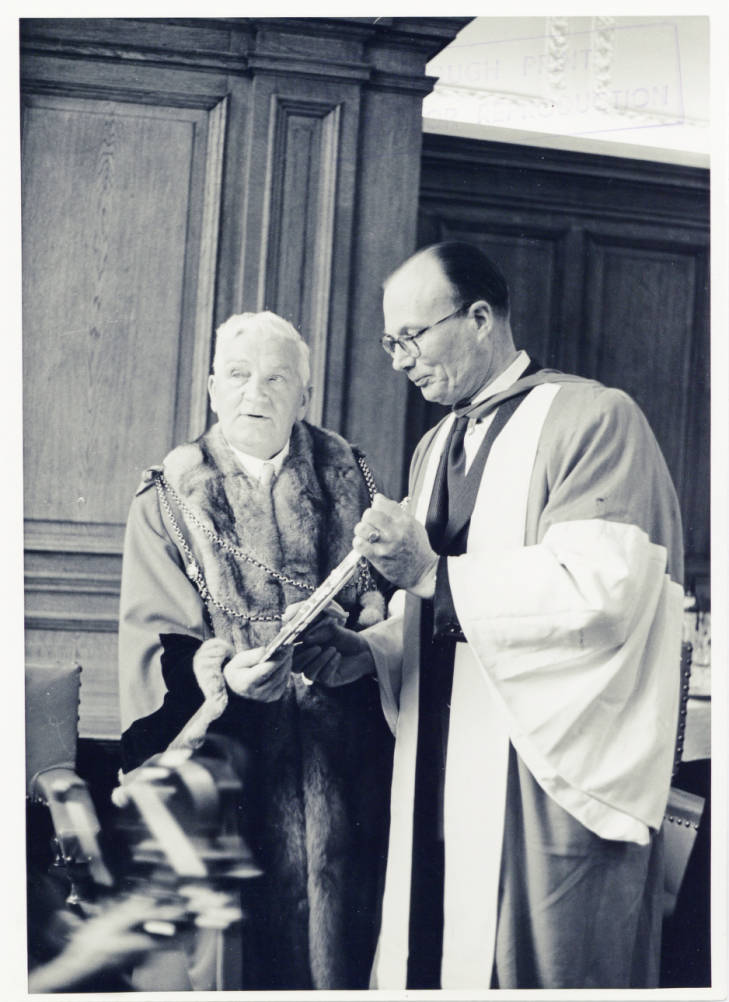

Esteemed surgeon and Emeritus Professor Frederick Charles Pybus (1883-1975), is perhaps best known to Newcastle University as a collector, donating his internationally significant library of some 2000 books on the history of medicine to the library in 1965. This remains one of Special Collections’ most impressive and prestigious resources of rare and unique published material, dating from the 15th Century with particular reference to anatomy, surgery and medical illustration and including influential works by luminaries such as William Harvey and Andreas Vesalius.

But Pybus himself is also remembered as a giant of the medical community and an influential figure both locally and nationally. A graduate of the Newcastle College of Medicine gaining his MS (Masters in Surgery) in 1910, Pybus’ long and varied career and lifelong associations with the Royal Victoria Infirmary and Newcastle University meant he is remembered as an authoritative voice on cancer research, surgical education and paediatrics. What is perhaps more surprising, and a story which has almost passed into folklore, is his hand in the creation of a household name; the energy drink Lucozade.

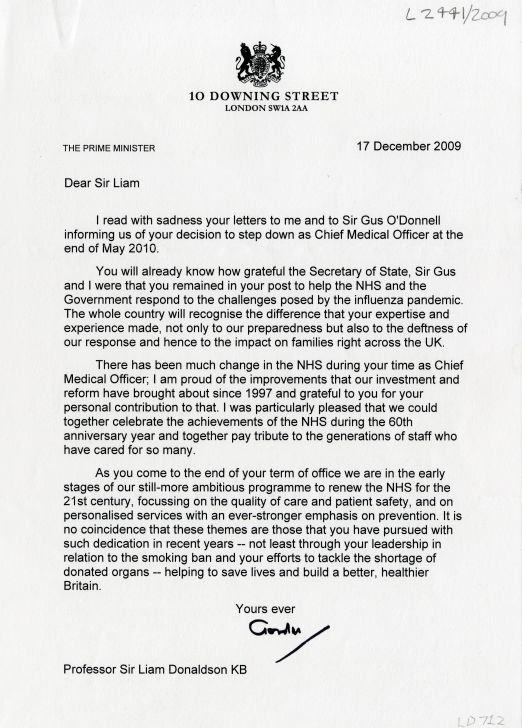

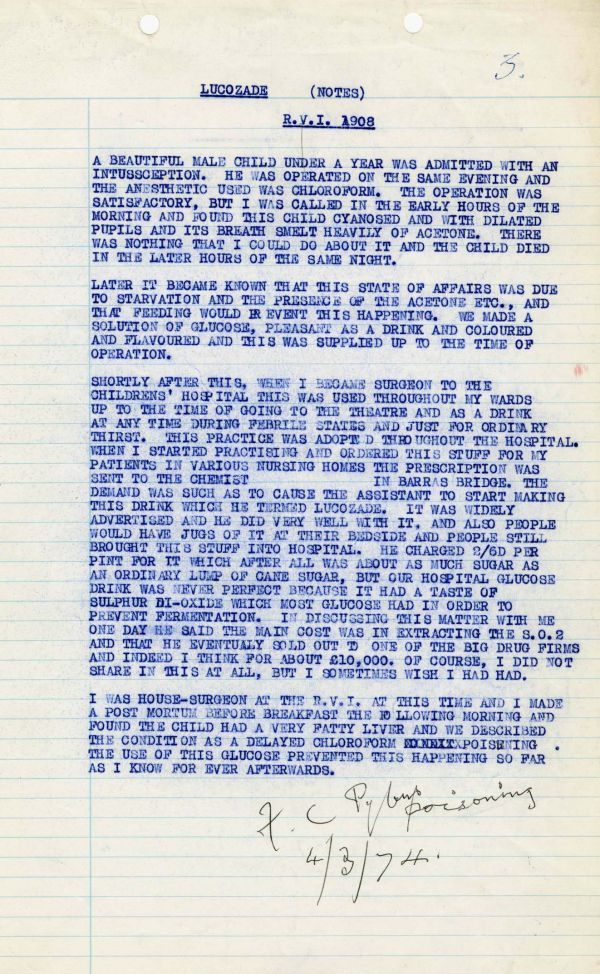

Pybus himself explains this story in this note present in his papers, which were donated shortly after his books. He describes how, during his student days working as a House-Surgeon at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in 1908, he lost a young patient following a seemingly successful operation. It was felt that this was because the child was starved, leading to them not being able to break down the chloroform used as an anaesthetic and resulting in a slow poisoning of the liver. This tragic event clearly affected the young Pybus and when he became surgeon at the Fleming Memorial Hospital for Sick Children following his graduation, he made sure patients drank a glucose drink he devised prior to surgery and when they had a fever to stop this happening again.

An enterprising chemist in Barras Bridge called William Owen provided the ingredients as a prescription, but noticing its popularity started making it himself and indeed perfected the recipe, with Pybus admitting his had “a taste of sulphur bi-oxide which most glucose had in order to prevent fermentation”.

Owen called this drink Glucozade, but, in 1938, Beecham pharmaceutical company realised the commercial potential and bought the formulae for the then princely sum of “about £10,000”, and Lucozade was born. Pybus admits in this note that although he had no share in this “I sometimes wish I had”. However, it was clearly a comfort that, in respect of the child that died, Pybus felt on his wards the Lucozade prototype “prevented this happening so far as I know for ever afterwards”.