Scientific Researches! – New Discoveries in Pneumaticks! – or – an Experimental Lecture on the Powers of Air, 1851 (Gillray Prints, JG/2/11R)

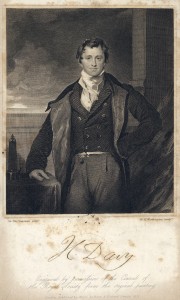

Engraving of Sir Humphry Davy from The life of Sir Humphry Davy, 1831 (19th Century Collection, 19th C. Coll. 530.9 PAR)

In one of his more robust parodies, this print from our collections by satirist James Gillray (1757 – 1815) is aimed at the spectacle and frivolity of scientific discovery in Georgian culture. The depiction of a public experiment is aimed at the Royal Institution (chartered two years before in 1800), which attempted to render complex scientific ideas comprehensible, but also provide an element of theatre. The accusation is that the latter often took precedence, devaluing breakthroughs at best and providing merely infantile parlour tricks at worst.

Amongst the recognisable figures, at the centre brandishing a pair of bellows is a young Sir Humphrey Davy (1778 – 1829) – chemist and inventor. Davy’s public experiments with nitrous oxide, or laughing gas, at the Pneumatic Institution in Bristol (hence the print’s title), led him to a post at the Royal Institution in 1801. Davy famously failed to grasp the significance of the gas as an anaesthetic except for minor surgery, treating it instead as a curio and conversation piece. Indeed, his often public experiments on himself led to a personal addiction and a reputation latched onto by commentators like Gillray.

Luckily, Davy’s legacy was much more significant. He was perhaps the first professional man of science and helped pave the way for many more like him, but this was not without further scrutiny and controversy. This included the eponymous Davy lamp, invented 200 years ago this month. By 1815, Davy had been knighted for his services to chemistry, including ‘discovering’ and naming potassium and iodine. By that point a scientist of international renown, he was called upon to solve a problem with a strong local connection.

In 1812, Felling Colliery was the site of an explosion caused by pockets of flammable gas referred to as ‘firedamp’ being ignited by the open flames of the miners’ lamps. Although not an isolated incident, this loss of 92 lives was a crystallised the need for greater safety precautions. Davy was personally asked by the Revd Robert Gray of Bishopwearmouth to investigate. As well as proving firedamp was in fact methane, Davy worked feverishly with his assistant and future pioneer Michael Faraday from October to December 1815 to produce a basic lamp with a wire gauze chimney to enclose naked flames. The holes let light pass through, but the metal of the gauze absorbed the heat and prevented the methane burning inside the lamp.

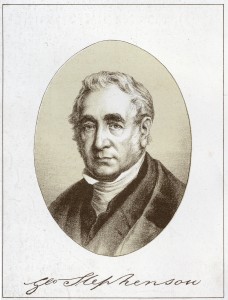

Engraving of George Stephenson from George Stephenson : the locomotive and the railway, 1881 (19th Century Collection, 19th C. Coll. 620.92 STE-1)

Following successful tests at Hebburn Colliery in early 1916, the lamp went into production. It proved to be Davy’s decisive triumph. He was awarded the Royal Society’s Rumford medal, and in 1820 became the President of that society, elevating his scientific field in the process.

However, the uniqueness of his invention was disputed. Davy refused to patent his lamp, and in doing so exposed himself to rival claimants, chiefly the then unknown engineer George Stephenson. Stephenson had been working on his own similar design at the nearby Killingworth Colliery north of Newcastle at around the same time through an arguably more scientific ‘trial and error’ approach. What followed was a public war of words with Davy rejecting Stephenson’s claims and winning out largely by virtue of his reputation.

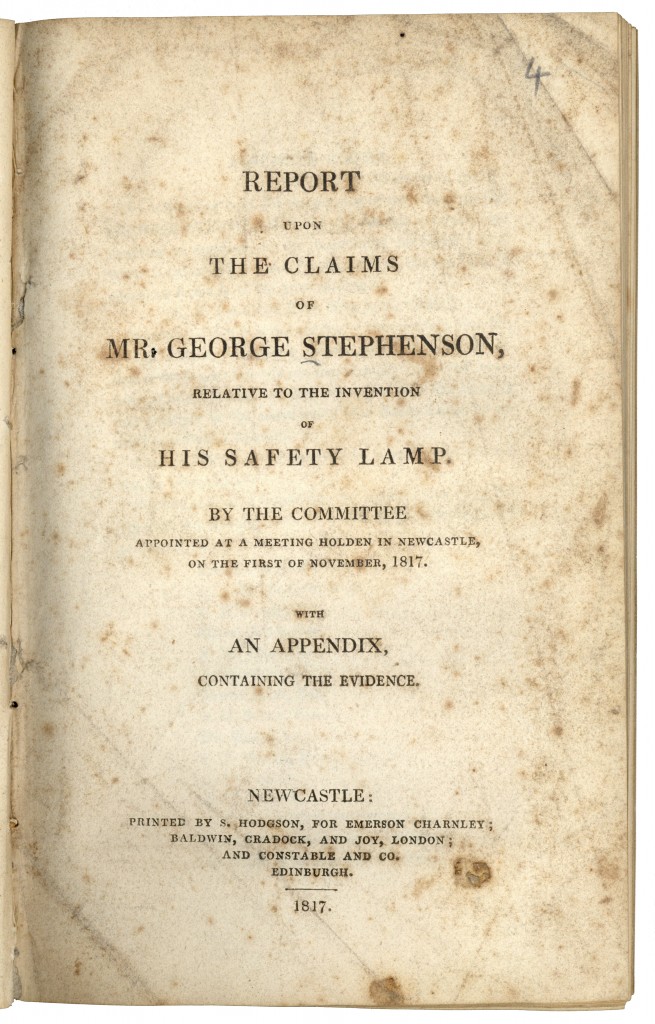

Despite this, on 1st November 1917, Stephenson presented evidence to a committee of his peers in Newcastle, claiming his invention was at least contemporary to Davy’s. In this report, available in our Rare Books Collection (image shown below), both miners and members of the Literary and Philosophical Society give testimonies on witnessing the other lamp being developed and tested as early as August 1915. One Robert Summerside, an Overman in Killingworth Colliery, went as far as saying ‘Stephenson’s light produces a much better light than Sir Humphrey Davy’s’.

Title Page from Report upon the claims of Mr. George Stephenson, relative to the invention of his safety lamp, 1817 (Rare Books, RB622.47 REP-1)

At the meeting, it was decided that Stephenson was entitled to a public reward, but perhaps more importantly, his name was cleared in scientific and entrepreneurial circles. This allowed him to become one of the most important figures to the Industrial Revolution as Father of the Railways. It is also thought by some that his lamp, termed the Geordie Lamp after him by those that used it in the North Eastern coal fields, was the source of the term ‘Geordie’, as a shorthand for the people of Newcastle.

The committee concluded as follows:

Under the influence of these impressions the friends of Mr Stephenson will no longer dwell upon those intemperate and uncandid insinuations, respecting the clandestine acquirement of the principle in question, which have so lately been given to the world in the name and apparently under the authority of Sir Humphrey Davy, but which they are thoroughly convinced can never have obtained the deliberate concurrence of that enlightened philosopher.

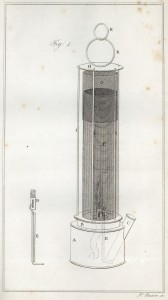

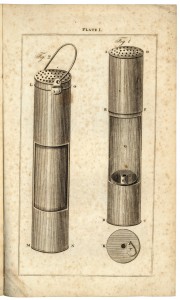

Below are 2 plates depicting the rival lamps; Davy’s on the right and Stephenson’s on the left.

Illustration of Sir Humphrey Davy’s safety lamp from Practical hints on the application of wire-gauze to lamps : for preventing explosions in coal mines, 1816 (Rare Books, RB942.8 TYN(VI)2)

Engraving of George Stephenson’s safety lamp from Report upon the claims of Mr. George Stephenson, relative to the invention of his safety lamp, 1817 (Rare Books, RB622.47 REP)