As part of the Special for Everyone project to address equality, diversity and inclusion in Special Collections & Archives, Finding their Voices is an exhibition celebrating the many diverse voices present within our collections.

Many of the voices within Special Collection & Archives have long been visible and heard, yet those from marginalised groups in society have often been obscured. Our Special for Everyone project is actively working to diversify the voices included in our collections and to illuminate the hidden or lesser-heard voices they contain. We are doing this by taking a fresh look at the sources and, where necessary, reading between the lines to uncover those which are harder to find.

Finding their Voices is a celebration of some of the people we have encountered through this work. It features people who found and made their own voices heard despite their often-marginalised position, and those whose voices have been more difficult to hear. We are amplifying them here to enable a new generation of researchers to discover them.

The exhibition contains items from across Special Collections & Archives. Below are some of the exhibition highlights:

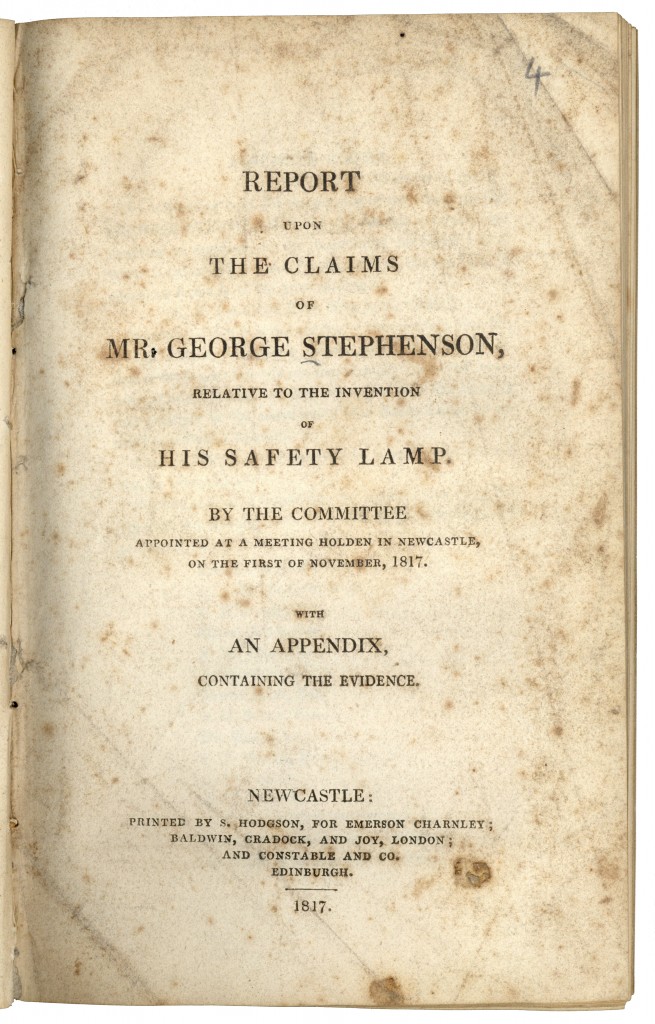

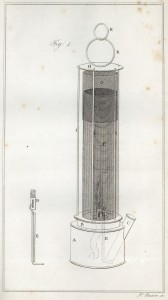

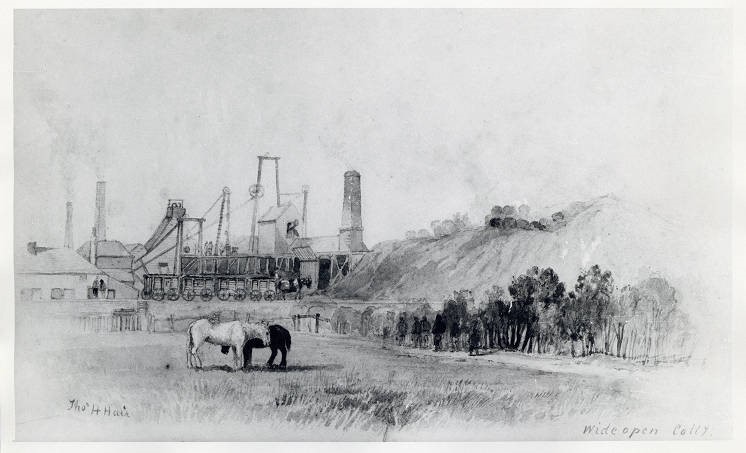

Working-Class Mining Communities

The lives of people from working-class communities in the past can often be difficult to discern within the official record. However, closer examination and interrogation of sources can help to uncover their history and voices.

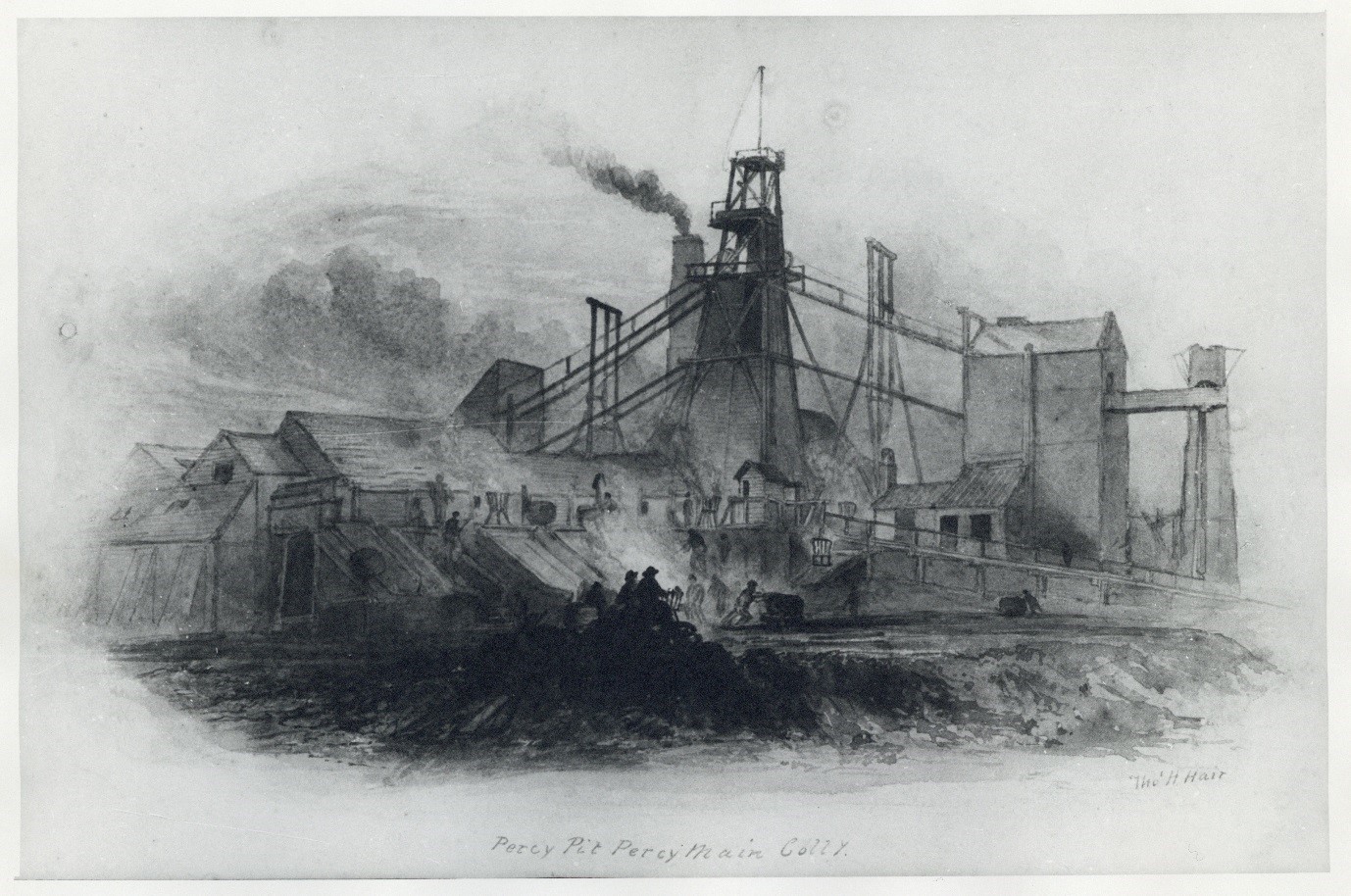

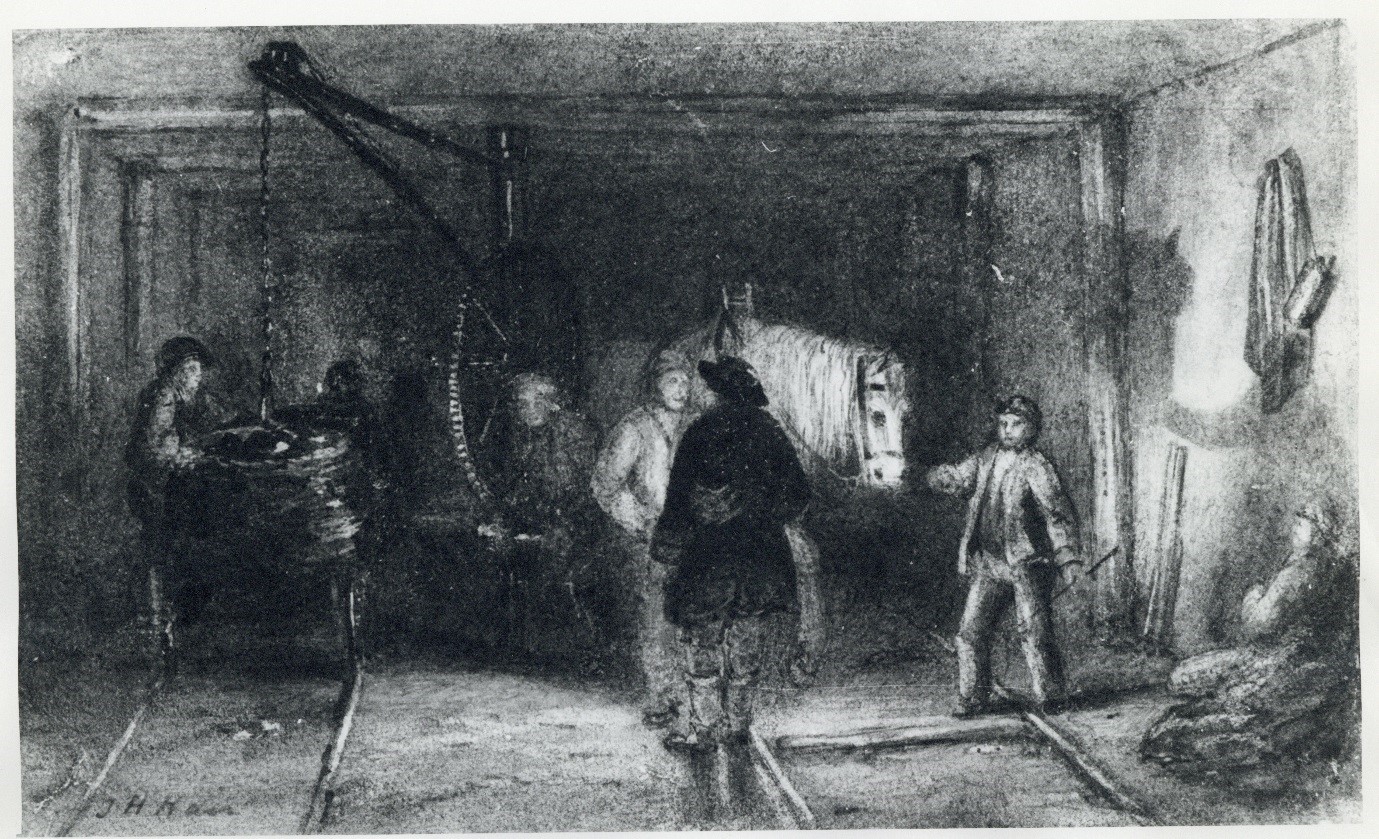

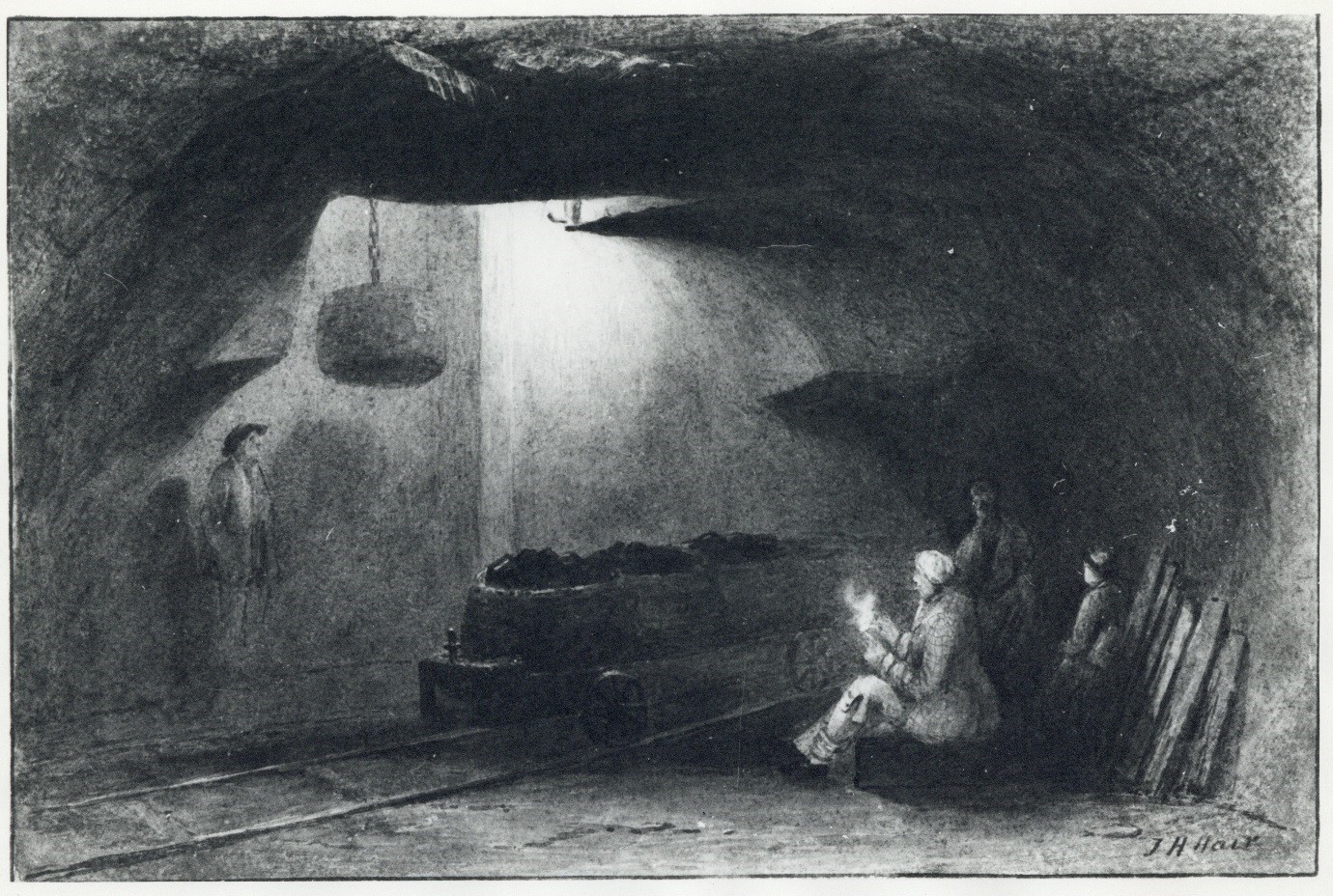

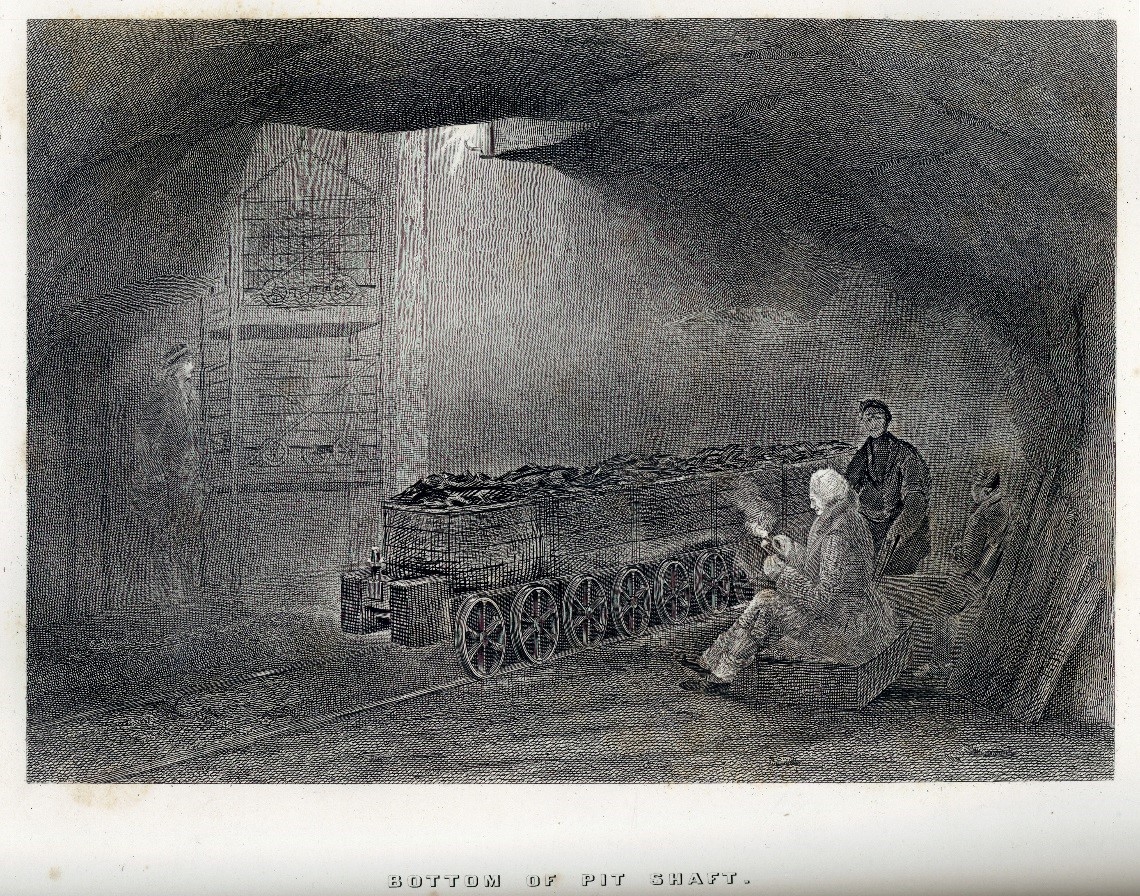

Thomas Hair (c.1810-1875) was a local artist whose illustrations depict the North East’s coal mining industry in the 19th century. His work captures the everyday workings of the industry, with many of the illustrations focussing on collieries, machinery, and river trade. Hair’s work provides visual evidence of the coal mining landscape and reveals the industry’s impact on the built environment. These images can tell us much about the lived experience of miners in this period, giving a ‘voice’ to their lives and the hard-working conditions they faced.

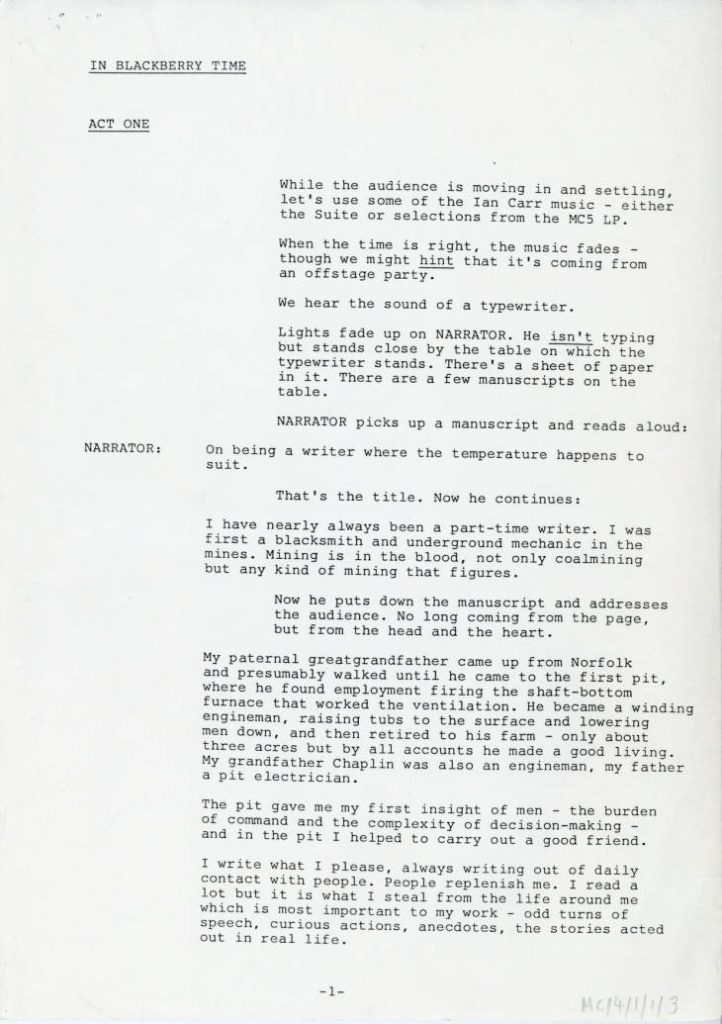

David Bateman and Shtum: the stutter poems

Poet David Bateman had a severe stutter as a child and teenager. He had successful speech therapy in 1980, aged 23. Since then, he still has a slight stutter in ordinary life but performs his poetry widely and has won many poetry slams and competitions. He writes poems, stories, scripts and articles. His book Shtum is a frank and personal account of what it is to have a stutter, the process of seeking the right help, and of finding your voice.

The poems in Shtum were mostly written between 2009 and 2015, but some have their origins in work from as early as 1980. David Bateman had never really considered writing about his stutter until he was prompted to think about how it was woven into his work when asked to participate in a radio documentary about stuttering in 2009. The project led him to return to some previously unpublished work made up of incomplete poems, unrealised ideas and prose diary entries. He felt ready to rework these early pieces and develop many new poems. The result is Shtum: the stutter poems.

The Pride Movement

The UK’s first Pride march took place in London on 1st July 1972 with around 2,000 participants. Over 50 years later, London Pride now sees over 1.5 million people marching together to celebrate LGBTQ+ rights. The Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) was established in Lancashire in 1964. Special Collections & Archives holds the archive for CHE’s Tyneside branch, including documents which illuminate the story of the Pride movement since that first march over five decades ago.

Within the Tyneside CHE Archive, it is possible to look back at Pride marches from across the past five decades. The first Pride march in 1972 took place 5 years after the Sexual Offences Act 1967 was passed, which decriminalised sex between gay men over the age of 21 in England and Wales. However, at the time of the first Pride march, the LGBTQ+ community still faced much discrimination. For example, gay marriage was not legal, and gay and bisexual people were banned from joining the armed forces. As well as campaigning, CHE also provided a social and support network for gay men and lesbians, providing a space for members of the LGBTQ+ community to make their voices heard.

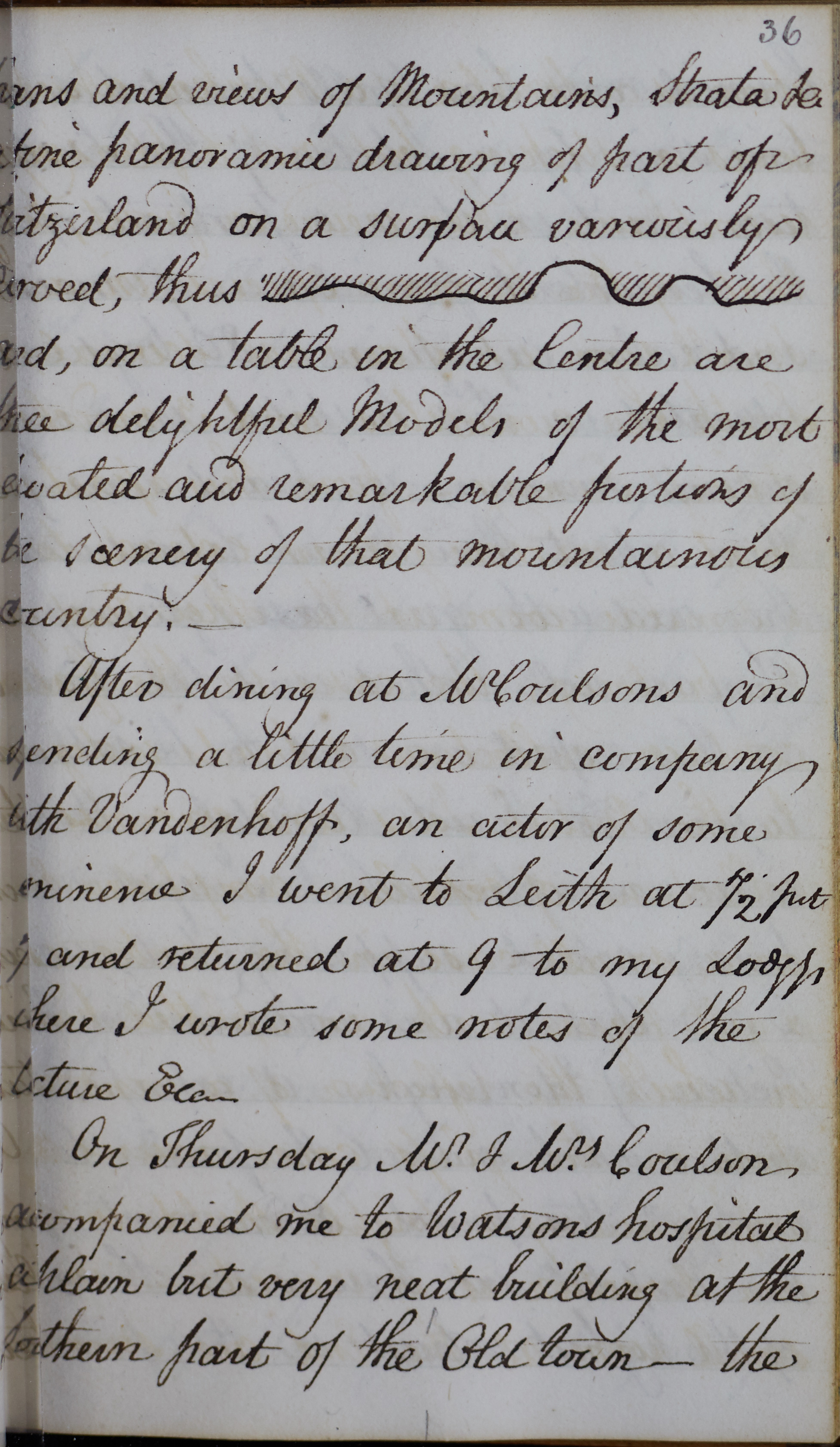

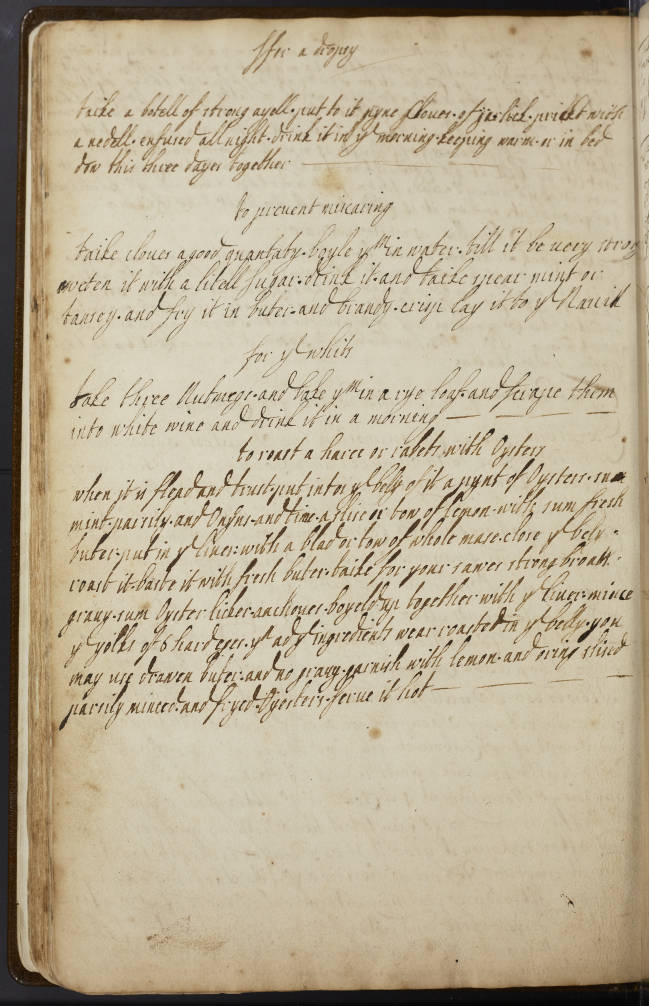

Female Friendships

The everyday lives and voices of women are often not well-documented. Through personal belongings such as books and correspondence, however, it is possible to gain glimpses into the ordinary day-to-day lives of women. We can see the importance of friendship amongst women, and the bonds and relationships they made through their social networks. In historical periods women found themselves in charge of running the household whilst their husbands were away at work. The exhibition highlights items which are testimony to the importance of companionship and mutual support between women and reflect how we can uncover their voices through what they left behind.

Jane Loraine’s recipe book from the 17th century contains a recipe ‘good for conception’, one ‘to prevent miscaring [miscarrying]’ and one ‘to make teeth white’. These recipes highlight the shared experiences of women and their attempts to help one another, not only with culinary recipes but also with fertility and more general health concerns. Different handwriting styles and recipes are attributed to different women. This indicates that the manuscript had multiple female contributors. Recipes were also often passed between class boundaries, highlighting the communal and collaborative nature of domestic knowledge in the early modern period.

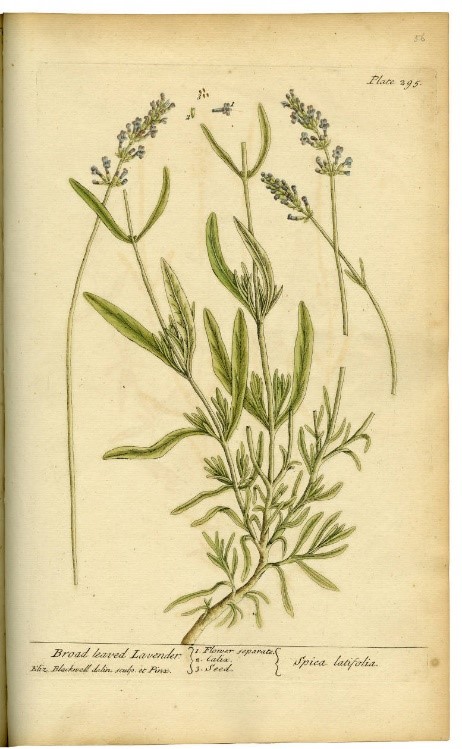

Professional Women

The classic image of women from the past is one of confinement, lack of agency, and a life of drudgery, domestic boredom or excess. In reality, whilst this might have been true for some, there have always been women who defied the expectations of their gender and exploited their talents to support themselves financially. Many gained a degree of respect in their chosen field and enjoyed popular success. Finding their Voices showcase items written and illustrated by women with talents and expertise in areas as diverse as science, art, storytelling, philosophy and pedagogy. Through their writings and illustrations their voices have a lasting impact.

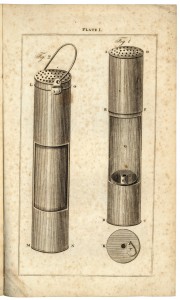

Elizabeth Blackwell (1707-1758) is one of the women highlighted within the Finding their Voices exhibition. She was the first woman known to have produced a book of botanical work in Britain. Despite having a wealthy background, she was forced to use her skill of botanical drawing to raise money to support herself and release her husband from debtor’s prison. Even more unusually, Elizabeth Blackwell undertook all stages of the illustrative process herself rather than employing specialist engravers and painters. She completed two volumes consisting of about 500 illustrations with accompanying commentary in under two years. The book was intended as a reference work for doctors who needed a thorough knowledge of medicinal plants.

Kamau Brathwaite and the Caribbean Voice

Barbadian poet, literary critic and historian Kamau Brathwaite (1930–2020) is a significant figure in the Caribbean literary canon, and one of its major voices. His work is noted for its rich and complex examination of the African and indigenous roots of Caribbean culture. He sought to create a distinctively Caribbean form of poetry which would celebrate Caribbean voices and language.

Kamau Brathwaite was born in Bridgetown, Barbados. Originally named Edward Lawson Brathwaite, he received the name Kamau from the grandmother of the Kenyan writer and academic Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, when on a fellowship at the University of Nairobi in 1971.

Kamau Brathwaite co-founded the Caribbean Artists Movement, a collaboration of artists which celebrated a new sense of shared Caribbean ‘nationhood’, in 1966. Caribbean identity and culture are central to Kamau Brathwaite’s academic writing as well as his poetry. Brathwaite felt that the traditional meter of the English iambic pentameter (where every line is composed of ten syllables and has five stresses) could not express the breadth and depth of that experience. He instead used African and Caribbean folk and jazz rhythms in his poetry. He combined that with the use of Caribbean dialect and patterns of speech to create a distinctively Caribbean form of poetry, which was written to be performed out loud and heard.

These items can be found alongside many others within the Finding their Voices exhibition on Level 2 of the Philip Robinson Library from Monday 10th April – June 2023.

Written by Daisy-Alys Vaughan, student working on the Special for Everyone project.