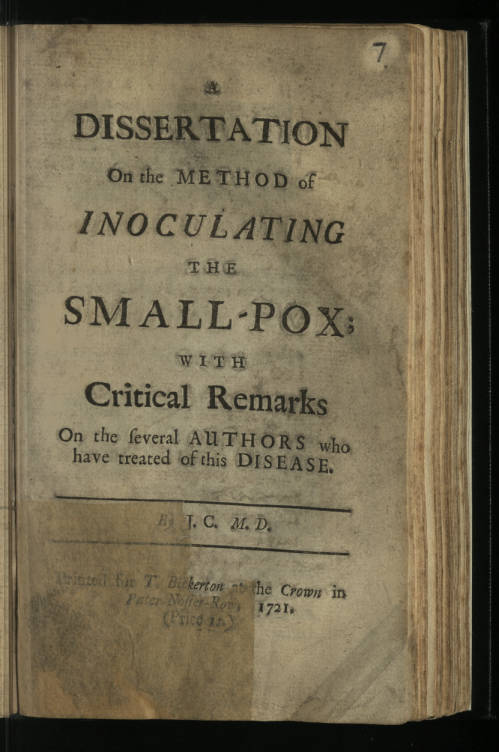

While we are all familiar with vaccination, its predecessor variolation is less well known. The goal is the same – to use a medical procedure to induce immunity to a disease. Before the invention of vaccination, variolation was the only preventative against smallpox available. This pamphlet, from our Medical Tracts Collection, is one of many English publications on the subject from 300 years ago in 1721. A translation of a Portuguese pamphlet by Jacob de Castro Sarmento, it outlines the variolation process ‘as it is practised in Thessaly, Constantinople and Venice’. The process is relatively simple – warm pus from someone suffering with smallpox is applied to a freshly made incision on the variolation patient. This triggers an immune response in the patient, which renders them less susceptible to future infection.

1721 was a key year in the history of variolation in England. While the practice had been taking place in Asia and Africa for some time, in the early 18th Century its adoption in England was cause of much debate. Since the 1710s the Royal Society of London had explored and discussed its use, but the high level of risk involved had prevented it from being introduced to English society. Arguments for and against the process continued to be published. Then in 1721, several events took place which contributed to its greater acceptance in England.

In April of that year, a smallpox epidemic led Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, an aristocrat and writer, to have her daughter Mary “engrafted”. Montagu had first encountered the procedure while in Turkey some years earlier. She had written about it to friends and had her son undergo the process whilst there. Back in England, Mary’s inoculation was observed by three members of the Royal College of Physicians, becoming the first documented inoculation in England. After the successful inoculation of her daughter, interest in variolation rose sharply amongst her aristocratic friends (which Montagu strongly encouraged. It came to the attention of Caroline of Ansbach, then Princess of Wales, who wished to inoculate her three children.

It was felt that more evidence of the safety and effectiveness of the procedure was required before risking the health of the heirs to the British throne, and so in July, the royal physicians finalised arrangements to conduct variolation trials on inmates at Newgate prison in London. Seven inmates were offered the choice of participating in exchange for their sentence of transportation to the Americas being remitted. Those who accepted (which was all of them) underwent “engrafting” on the 9th of August 1721. The initial procedure was heavily attended by observers and the participants’ progress was discussed in newspapers and pamphlets.

The Newgate trial was deemed a success, with all the participants recovering well and displaying immunity. One of the participants, Elizabeth Harrison (originally sentenced to death for the theft of 62 guineas), was taken to a school which was suffering a smallpox outbreak to demonstrate her immunity. The royal children were eventually inoculated, but not until April 1722 after further trials on orphan children had taken place. While debate continued around the safety and effectiveness of variolation, these events contributed to its increased acceptance and by the 1740s, charitable inoculation hospitals were being established. It became common practice to use variolation to reduce the impact of smallpox outbreaks in rural areas. Variolation continued to be used in England until the invention and introduction of the safer vaccination process eventually led to the Vaccination Act of 1840. This entitled everyone in England to smallpox vaccination free of charge and banned the use of its riskier predecessor.

Read the whole pamphlet on CollectionsCaptured.