Thank you to Universities at War volunteer (and retired member of Library staff!) Alan Callender for this blog piece and for all of the hours of painstaking research behind it.

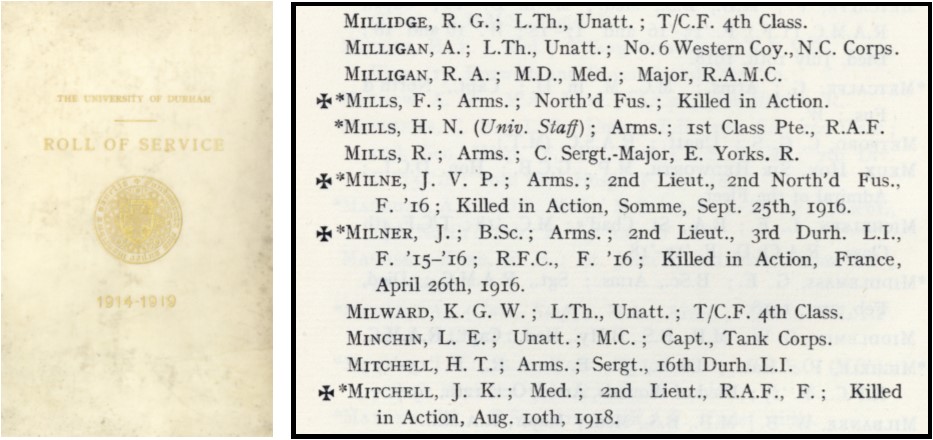

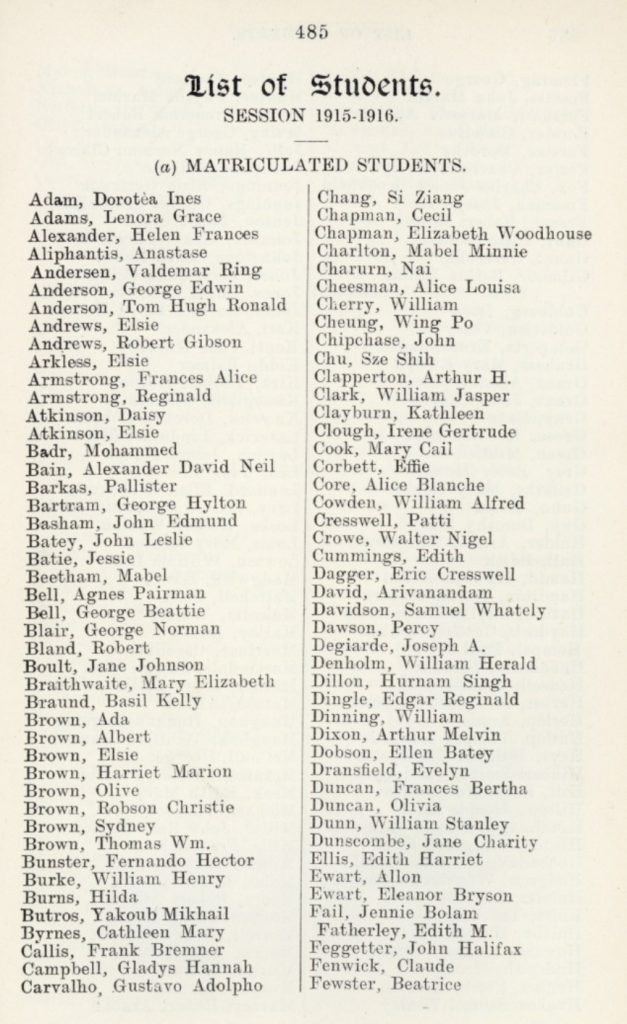

The University of Durham Roll of Service, produced in 1920, lists 2,464 staff and students who had served in World War One from the various Colleges that made up Durham University at that time. These include men and women from Armstrong College and the College of Medicine at Newcastle upon Tyne, predecessors to Newcastle University.

Only four of our female graduates appear in this book, but this hides the fact that many of our female staff and students, particularly our medical graduates, did serve in military units. These women, usually categorised as serving under “unofficial” women-only military units, were denied the criteria for the Roll of Service which required them to belong to a unit which appeared in the “official lists of the Navy Army or Air Force”. This article is intended to honour the women whose wartime stories deserve recognition.

Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service

The Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Services (SWH) was founded in 1914. The SWH was spearheaded Dr Elsie Inglis, as part of a wider suffrage effort from the Scottish Federation of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, and funded by private donations, fundraising of local societies and the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, and the American Red Cross. As voluntary all-women units, the Scottish Women’s Hospitals offered opportunities for medical women who were prohibited from entry into the Royal Army Medical Corps. By the end of the War 14 medical units had been outfitted and sent to serve in Corsica, France, Malta, Romania, Russia, Salonika and Serbia. Over 1,000 women from many different backgrounds and many different countries served with the SWH.

We have found six graduates from the College of Medicine who served under the SWH:

Dr Ruth Nicholson (M.B., B.S. 1911) served as Surgeon and Second in Command at the Royaumont (France) Unit from 1914-1919.

Dr Lilian Mary Chesney (D.P.H. 1908) served as a doctor in the Kragujevac (Serbia) Unit 1914-1915 and the London (Russia and Serbia) Unit from 1916-1917. Thanks to the research of John Lines whose great aunt, Margaret Box, also served with the SWH, we have evidence that by October 1918 Dr Chesney appears to be running the hospital in Skopje (Serbia) for the SWH. Margaret refers to Dr Chesney in several of her wartime letters and calls her “our chief”.

Dr Sophie Bangham Jackson (M.B., B.S. 1904 and M.D. 1906) served as a doctor in the Ajaccio (Corsica) Unit 1916-1917.

Dr Margaret Joyce (M.B., B.S. 1898) served as a doctor in the Royaumont (France) unit in 1915.

Dr Elizabeth Niel (M.B., B.S. 1907, M.D. 1909, D.P.H. 1910) served as a doctor in the Sallanches (France) Unit 1918-1919.

Dr Grace Winifred Pailthorpe (M.B., B.S. 1914 M.D. 1925) served as a doctor in the America (Serbia) Unit 1916.

Women’s Hospital Corps

Under the leadership of militant suffragists Dr Flora Murray and Dr Louisa Garrett Anderson, the Women’s Hospital Corps (WHC) ran a military hospital at the Claridge Hotel in Paris and then at Wimereux, for the French government (their proposals having been rejected by the British authorities). In 1915 however the War Office asked the WHC to set up a military hospital in London entirely staffed by women. It became known as the Endell Street Military Hospital. Open from May 1915 to December 1919, its doctors treated 26,000 patients and performed over 7000 major operations.

Co-founder and Surgeon Dr Flora Murray undertook her medical training at the London School of Medicine for Women and was a registered student at the College of Medicine in Newcastle 1900-1902 from where she graduated M.B., B.S. in April 1903 and M.D. in April 1905.

Dr Florence Barrie Lambert (M.B., B.S. 1906) served as Chief Medical Officer for the WHC until 1916 and was then appointed by the R.A.M.C. as Inspector of the Electrical and Massage Departments for the British convalescent camps.

Voluntary Aid Detachment (V.A.D.) Hospitals

Although not “official” military hospitals, in reality V.A.D. Hospitals often became auxiliary hospitals to larger military hospitals.

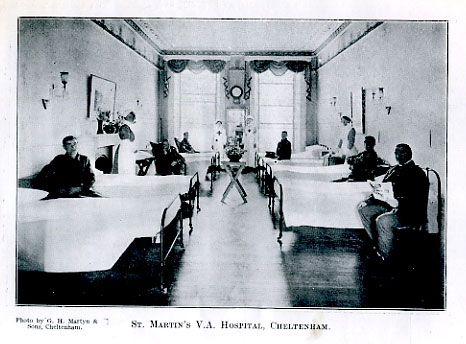

Dr Grace Harwood Stewart Billings (M.B., B.S. 1898) served as Medical Officer of the St Martin’s V.A.D. Hospital in Cheltenham. This is from the final report of the Red Cross Gloucestershire, 1914-19: “St. Martin’s Hospital was opened in June 1915 at Eversleigh, Bayshill, with accommodation for 40 patients. It was entirely staffed by former pupils of the Ladies’ College, Cheltenham. At first it was only intended to be a convalescent hospital, but in a very short time this was altered and patients came direct from the front the same as to all the other hospitals in the town.” The Chief Officers are listed in this report as:

Commandant: Miss Donald

Medical Officer: Dr Grace S Billings

Superintendent: Miss Wintle A.R.R.C.

Royal Army Medical Corps Units and the British Army

In fact some female medical graduates did serve as doctors within the British Army during the War, despite the British authorities’ official stance.

The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), re-named in 1918 the Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Army Corps (QMAAC), was set up in 1917 as a voluntary unit under the British Army. It eventually employed 57,000 women in a range of occupations. For female qualified doctors there were opportunities here to serve alongside their male counterparts, although they were never allowed to serve officially under the Royal Army Medical Corps.

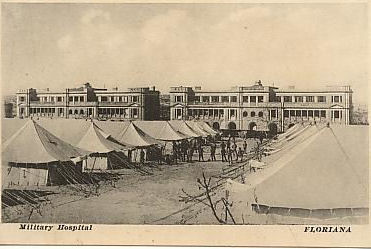

A second route came in 1916 when an acute shortage of male doctors led to a change in policy. To fill the gap the War Office decided to hire a number of women doctors as ‘civilian surgeons’ who were to be attached to RAMC units serving in Malta, the main hospital base for the Mediterranean Theatre of War. In total 85 women doctors were hired.

We have found three medical graduates who served in the British Army via these routes:

Dr Stephanie Patricia Laline Hunte Taylor Daniel (M.B. 1917, B.S. 1918) served as Medical Official in the QMAAC, stationed at Catterick Camp, from 1917-1919.

Dr Ethne Haigh (M.B., B.S. 1913) served as a Civilian Surgeon under the RAMC, and was stationed at Floriana Military Hospital (Malta) 1916-1917 and No. 65 General Hospital in Salonika 1917.

Dr Ida Emelie Fox (M.B., B.S. 1902) served as a Civilian Surgeon under the RAMC and was stationed at No. 65 General Hospital in Salonika, 1916-1918.

Nurses for the British Army

Two of the women who appear in the Roll of Service were graduates or students of Armstrong College who during the War served as nurses for hospital or ambulance services registered under the British Army, thus meeting the criteria of the Roll of Service.

Janet C. Brown (Armstrong College) served as a nurse for two military hospitals during WWI, 1st Southern General Hospital (Birmingham) 1916-1917 and 1st Northern General Hospital (Newcastle upon Tyne) 1917-1919.

Clementine Mary Hawthorn (Armstrong College A.Sc. 1903, B.Sc. 1904) served as a nurse in the 1st Northumberland Field Ambulance 1914-15.

The Wounded Allies Relief Committee

Dr Olivia Nyna Walker (M.B., B.S. 1911) served as Assistant Surgeon at the Hospital Anglais, Lycée de St-Rambert, L’Ile Barbe, Lyon, France. This was a temporary French military hospital which operated 1914-1916 under the direction of the Wounded Allies Relief Committee.

Interested in viewing more stories from WWI uncovered by our researchers? You can do so by finding out more information on the Universities at War project. You can also view The University of Durham Roll of Service online.