Newcastle University Library Special Collections and Archive hold the Thomas Sopwith Diaries covering the period 1828-1879.

Thomas Sopwith (1803-1879), as well as being a successful engineer who contributed extensively to the Victorian railway and mining industries, Thomas Sopwith was the author of a set of diaries that now live in the Special Collections archives.

Born in Newcastle in 1803, Sopwith discovered his love of writing as a teenager, and from the age of 18 kept a careful account of his every move in a series of pocket-sized hardback diaries. With only a few breaks, at times when he was really busy, he continued to write for the next 58 years, creating 168 volumes in total.

Sopwith was passionate about his work, and his dairies are a fastidious account of his meetings, projects and professional engagements. From 1845 to 1871 he was the chief agent of Allenheads lead mines in Durham and felt it would be imprudent to discuss the finer points of his role, reserving his diaries for more personal news.

Before his move to Allenheads, however, he worked as a kind of engineer-about-town, surveying railways, giving evidence in mining enquiries and touring the country with his renowned 3D models of the Forest of Dean coalfields. And documenting it all in often absurd levels of detail in his diaries.

One of the most striking things about the diaries is the sheer number of prominent Victorian figures who make an appearance. Sopwith was good friends with William Armstrong and George and Robert Stephenson and must have known nearly all the major names in science and engineering at the time. One week he might be staying with the Brunel family, the next he’d be dining with the King of Belgium, before travelling round the Norwegian fjords with Robert Stephenson. Sopwith was full of praise for almost everyone he knew and was a man who really valued his friendships.

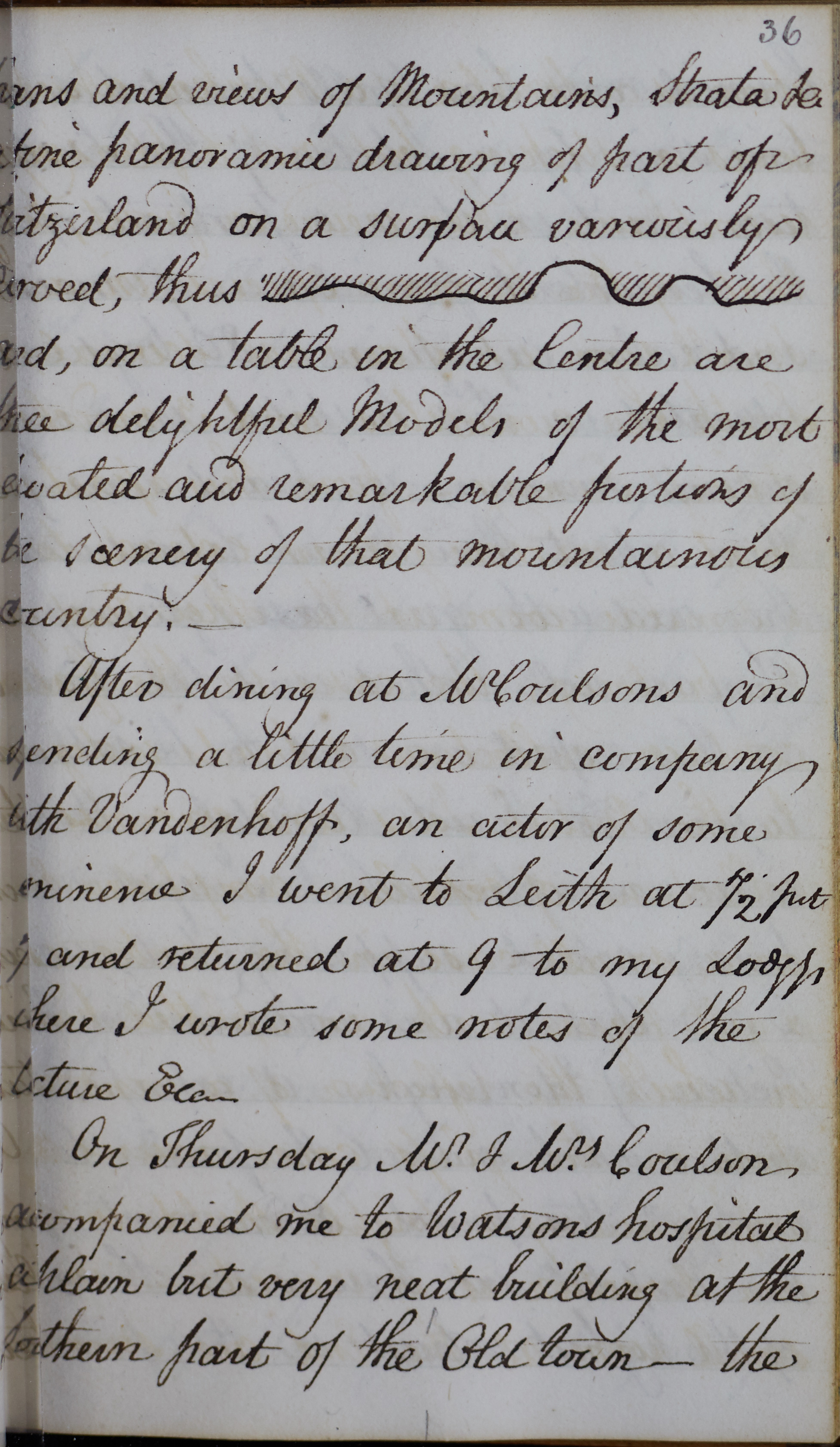

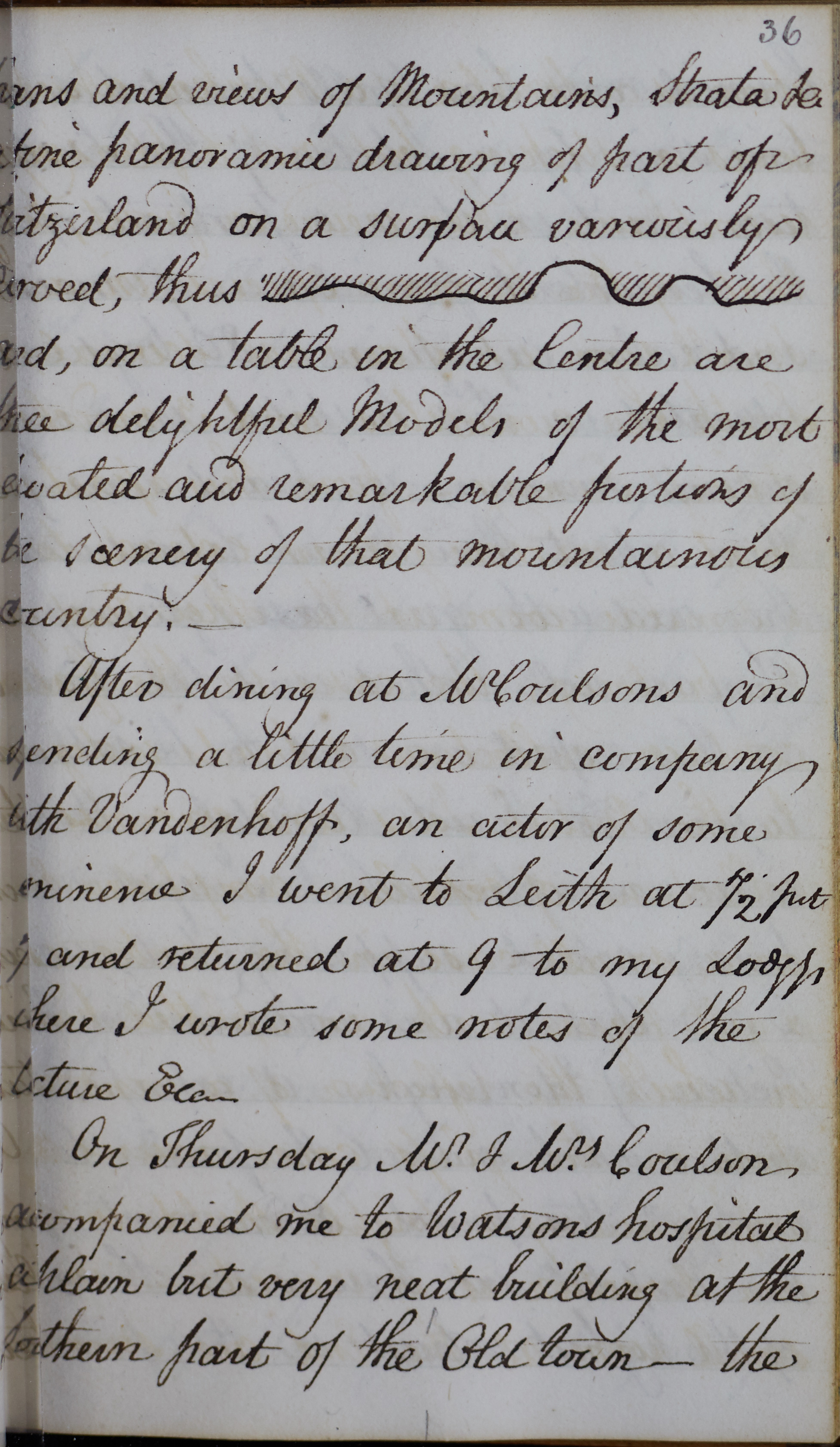

Page from Sopwith’s diary dated April 1828 (Thomas Sopwith Diaries, TS/1/1)

When he wasn’t hobnobbing with the great and the good, Sopwith spent time at home with his large family. Married three times and widowed twice, Sopwith had eight children (two died in infancy) and doted on them all. His wayward eldest son Jacob caused him a great deal of worry and – spoiler alert – the diaries contain a fair few deaths, often prompting pages of reflection by Sopwith on religion and fate.

Many of his descendants went on to prominent careers themselves; one daughter married an MP, one grandson became the Archdeacon of Canterbury and another was an aircraft designer whose son was a racing car driver.

The diaries are littered with pencil and watercolour sketches and Sopwith often pasted in newspaper cuttings or even a menu from a banquet he attended in Belgium. The handwriting is immaculate and Sopwith’s use of symbols for days of the week, abbreviations and explanatory diagrams shows his love of efficiency.

Page from diary dated 24th April 1828, depicting a watercolour sketch of Abbotsford (Thomas Sopwith Diaries, TS/1/1)

Sopwith’s diaries also give a charming account of middle-class life in Victorian Newcastle. Sopwith was a frequent guest at Mr Donkin’s dinner parties in Jesmond and in the 1840s lived in a house he had had built on St Mary’s Place, nowadays part of Lloyds Bank. He maintained an interest in his family’s furniture-making business and was most indignant to discover that a railway viaduct was to be built right next to his workshop on Painter Heugh, blocking the natural light – a rare case of opposition to the railways.

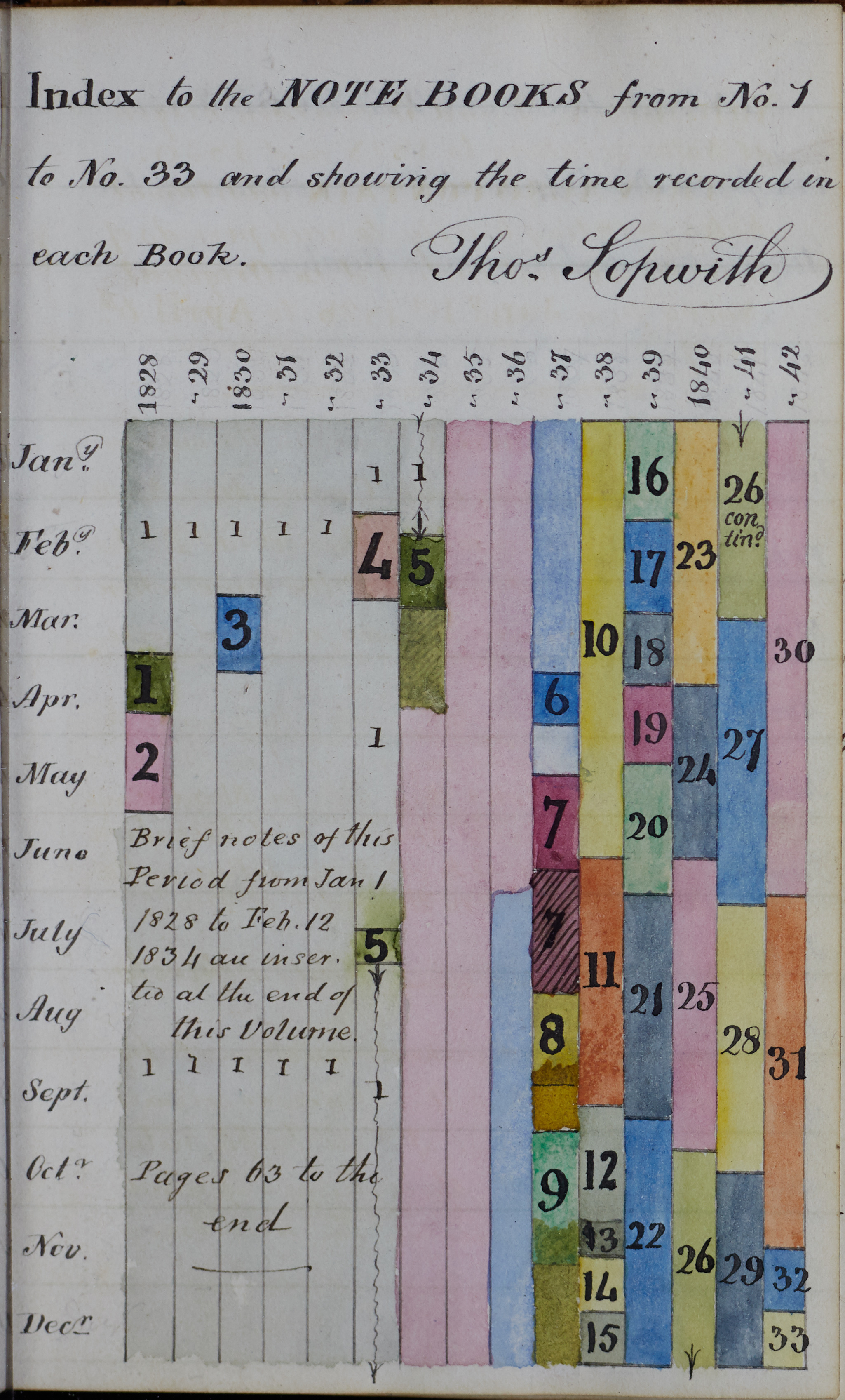

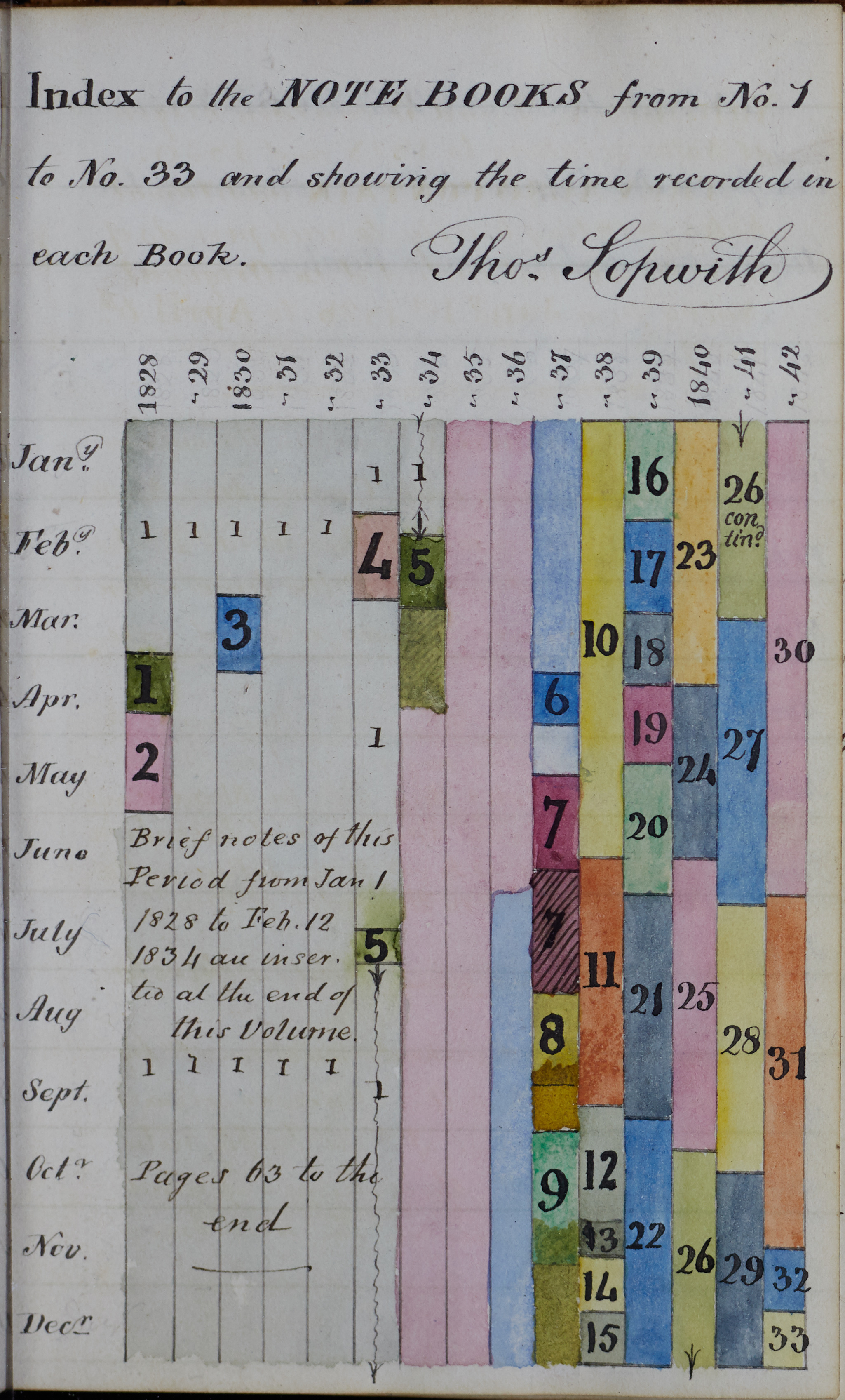

Pedantic to the extreme, Sopwith’s exacting nature seeps through the pages of his diary in a surprisingly charming manner. From the intricate contents pages and indexes of the volumes themselves to his use of a telescope to make sure the children at Allenheads school turned up on time, Sopwith was nothing if not meticulous.

Index to the notebooks from no.1-no.33, 1829-1842 (Thomas Sopwith Diaries, TS/1/1)

Why did Sopwith keep such detailed diaries? He seems to have really enjoyed the process of recording and reflecting on his daily activities, and frequently mentions his joy in re-reading old passages and remembering old friends.

The diaries are so detailed that it’s hard not to get sucked in to the soap opera of Sopwith’s life. The sometimes dry accounts of his engineering work and academic interests – one diary includes a 13 page report from a lecture on fattening cattle – is always balanced with anecdotes from his family life or his fussy musings on the state of modern society.

Reading the whole set of diaries might be a tall order, but dipping into a volume or two opens up a window onto one of Victorian Newcastle’s most notable figures.

Written by special guest, Mark Sleightholm