This piece was originally written for Policies for Equitable Access to Health, an Italian-based site that now offers a valuable ‘weekly snapshot of public health challenges’. It is reposted here with their kind permission.

Much of my academic work over the past 20-plus years has focussed on the processes of globalisation and what they mean for population health. One of the early (2007) major products of that work, co-written with long-time colleague Ronald Labonté, came out of analysis done for the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of health. It took the form of a three-part series in the journal Globalization and Health, discussing in turn historical context and methodological background; the role of the global marketplace; and prospects for promoting health equity in global governance. (The later work on globalisation that informed the WHO Commission appeared in book form in 2009.) In view of the cataclysmic world events of the last 30 months (at this writing) and my pending retirement from salaried academic life, I thought it useful to look back on some of our analysis to see what it got right, what it neglected, and how future research should learn from such reflections.

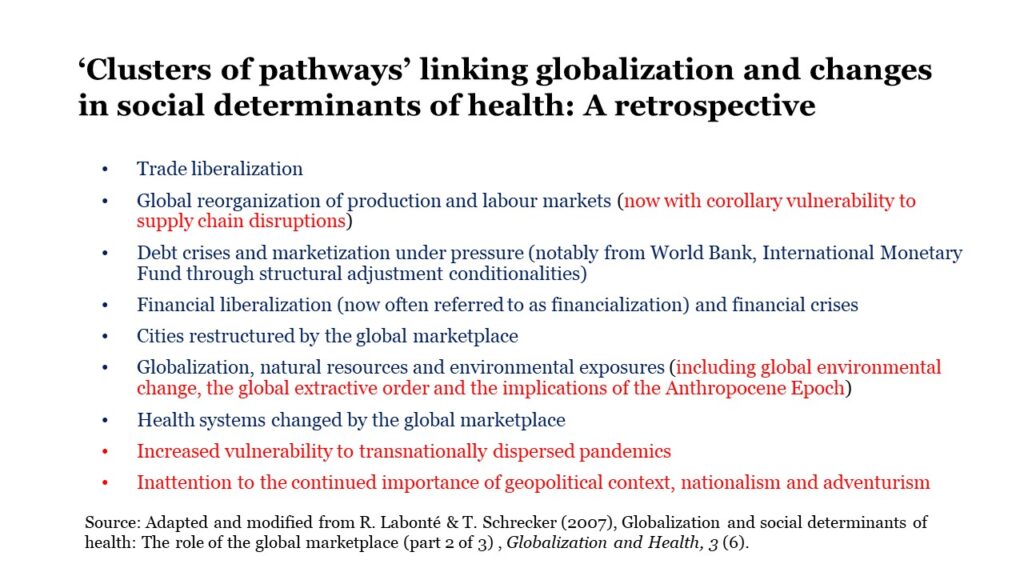

The work focussed, quite rightly in my view, on how the emergence of a global marketplace and the associated worldwide spread of neoliberal economic ideas and institutions transformed opportunities to lead a healthy life and the options for public policy to reduce health inequalities. Indeed, we perhaps did not focus intensively enough on neoliberalisation and its transformative impact, about which I have written elsewhere. The figure below shows (in blue) the seven interacting ‘clusters of pathways’ that we identified in Globalization and Health, and (in red) how I think this analysis needs to be modified and added to in light of recent events. The rest of this post concentrates on three areas, obviously in insufficient detail.

The first of these relates to the consequences of global environmental change, now observable in daily headlines about such climate-related phenomena as shrinking polar ice cover, heat waves, megadroughts and wildfires. As conspicuous as these impacts are, the reflect only one dimension of what is now widely described as the Anthropocene Epoch – a new era of geologic time marked by the scale and extent of human-induced changes in the natural environment, exemplified by (for example) the prospect of the transformation of the Amazon rainforest into savannah as a result of continuing deforestation. A key concept in the Anthropocene literature is the Great Acceleration, a multidimensional speeding up of economic activity and the associated biophysical transformations beginning, on many reckonings, around 1950 with the post-World War II period of economic growth. Until recently, that growth was concentrated in the (mostly high-income) OECD group of countries. Formidable questions of global justice are raised by the implausibility of sustainable growth within planetary boundaries if the rest of the world were to continue pursuing anything like the standard of living taken for granted within the OECD. Anthropologist Jason Hickel has been one of the most vocal and articulate proponents of ‘degrowth’ in this context; whether intentional degrowth is feasible under any kind of democratic political arrangements is a question yet to be resolved.

The second area of neglect relates to the continued, indeed enhanced danger of transnationally dispersed pandemics. With 20-20 hindsight, there was little reason for this. Journalist Laurie Garrett had been warning of the prospect since 1994, and in 2019 – just a few months before the start of the Covid-19 pandemic – published a prescient article warning that: ‘The world knows an apocalyptic pandemic is coming … But nobody is interested in doing anything about it’. This problem does not appear at first directly connected with the global marketplace, but in fact it is. Public health infrastructure is one of the key prerequisites of societal survival that the so-called free market cannot and will not provide; it is one of the few truly public goods for health. The neoliberal turn in public policy is thus implicated in the neglect of public health infrastructure to the extent that Matthew Sparke and Owain Williams recently (and correctly in my view) identified Covid-19 as a ‘neoliberal disease’. Incredibly, if predictably given the current UK government’s tenuous hold on reality, it has not learnt from the pandemic: in April 2022 the government announced staff reductions of 40 percent at the Health Security Agency, responsible for pandemic planning and response, at the finance ministry’s insistence. In the same month, again predictably, a scientifically illiterate US Congress refused to continue Agency for International Development funding for vaccine delivery in low-income countries.

Third and finally, researchers like myself took too seriously and literally the idea of a ‘Borderless World’ put forward by Japanese economist Kenichi Ohmae. The book in question, originally published in 1990, remains an iconic paean to a world in which governments have become largely irrelevant; ‘if a corporation does not like its government, it can move its headquarters to other, more hospitable places’; and the future resembles nothing so much as a global duty-free shop. Many elements of this vision, notably its focus on the footloose corporation and its tacit acceptance of rising inequality, remain accurate if dispiriting descriptions of the world economy. At the same time, nationalism and geopolitics continue to render the world anything but borderless, and political institutions anything but irrelevant, in many respects. In 2016, UK voters narrowly supported leaving the European Union and its single market, an act of economic self-harm that will have consequences for decades, most of them magnifying existing inequalities and their destructive effects on health. And several European countries, Germany most particularly, appear to have believed that the world really was borderless for purposes of energy policy. This catastrophic inattention to geopolitics led directly to today’s vulnerabilities associated with reliance on Russian natural gas supplies and may yet pave the way to deep recession, widespread social unrest, and domestic political pressure to accept Ukraine’s dismemberment. Much of this could have been avoided through careful attention to a long list of books drawing attention to Russia’s internal political transformation, going back at least to the late Anna Politkovskaya’s 2004 Putin’s Russia. (She was murdered shortly after its publication.)

Much more can and should be said on all these matters, and others. For example, global health researchers have not yet come to grips with the implications of a widespread retreat from democracy and drift into autocracy in which, according to the respected Varieties of Democracy Institute, ‘the last 30 years of democratic advances following the end of the Cold War have been eradicated’. As historical sociologist Margaret Somers points out in the US context, this trend is not unrelated to the hegemony of neoliberalism, although the connections are likely to vary among country cases. Faced with such complexity, many researchers will be tempted to retreat into the familiar territory of health systems design and what might be called global medicine. This tendency should be resisted, not least because – as Martin McKee notes in an important recent article – ‘politics is at the heart of public health’. This is even more true in the global frame of reference than at the national level about which he was writing.