If you’re a Master’s student, then this time of year is less about walking on sunshine and more about working to deadlines. But, if you’re busy wrangling that dissertation, worry not, for the WDC is on hand with these super helpful resources!

- Read All About It

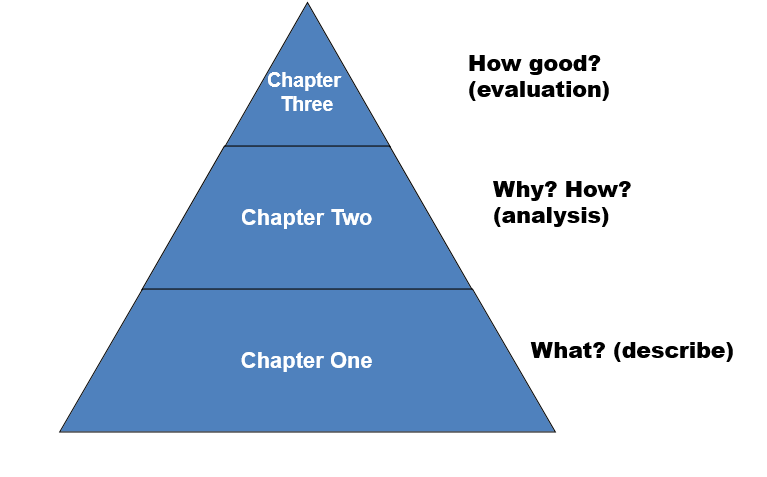

Doing a dissertation involves so. Much. Reading!! Often, you’ll need to read things more than once to develop your ideas and understanding. Here at the WDC, our modest assessment of our Three Domains of Critical Reading is that it is completely and utterly brilliant, and can really help you get the most out of your reading.

2. Making Sense of It All

Once you’ve done the reading, you then need to pull it all together. What are the common themes and patterns? Where are the gaps? What does it all mean?! Our – again, we’re being modest and objective here – absolutely splendid Mapping the Literature resource can be a great way of making sense of all your reading. Perfect if you’re working on that literature review!

3. Let’s Talk it Over

Speaking of literature reviews … here we are, quite literally, speaking of literature reviews! Now, this Q&A discussion, led by WDC tutors Helen and Caroline, was filmed for a lovely group of PhD students in the SAgE faculty. However, it does contain lots of top tips that can be applied to literature reviews at Master’s level, too, such as advice on structuring and writing critically. The video is handily timestamped, too, so you don’t have to watch the whole thing. Unless you really want to …

4. It’s All Under Control

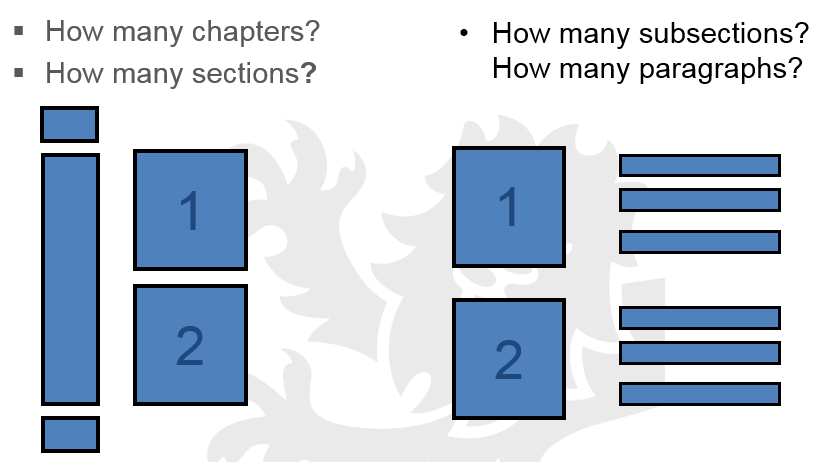

Odds-on, the dissertation is the longest piece of writing you’ve ever produced. The longer a piece of writing is, the harder it gets to stay in control of your material. Hence, trying to structure your dissertation and ensure everything makes sense might not be the most fun you’ve ever had. Luckily, the WDC is on hand with some top tips on getting everything to hang together.

5. Never Out of Style

Once you’ve got all those ideas down on paper, it’s all about polishing up your writing for your reader and presenting that academic persona that they’re looking to see. Once again, the WDC has you covered with our handy tips on academic writing style.

6. Proof it!

The last thing anybody wants to do when they’ve just finished writing a long, complex piece of work is go through it with a fine toothcomb looking for all the things they might have got wrong, Unfortunately, this really *is* the last thing we have to do, But, yes, you’ve guessed it! The WDC has a brilliant Study Guide positively brimming with handy proofreading hints!

7. Words, words, words

Student at the very start of their dissertation: I will never be able to write that many words EVER.

Student towards the end of their dissertation: How have I managed to write 2000 words more than I was supposed to?!

Is this you?! Then read this.

8. When the going gets tough

We’ve all be there: we really need to write but we can think of 2,908 things we’d rather do instead. Sounds familiar? Check out the WDC’s top tips on staying motivated and productive this summer.

9. When the going gets tougher …

Working on a Master’s dissertation isn’t easy at the best of times and, let’s face it, the summer of 2020 is *not* the best of times. We put together some time management tips for troubled times back in spring. If, quite understandably, you’re finding it difficult to focus on your work this summer, check out our advice on how to be kind to yourself and boost your productivity.

And remember, if you’d like to discuss an aspect of your work with one of our WDC tutors, they’re still here for you over the summer and are offering appointments via Zoom.