Students often feel their concentration should be focused on how to manage their work, how to meet deadlines, how to navigate their ways through massive amounts of reading… However, it is also important to think carefully about the question ‘how do I manage rest?’ At the WDC we frequently hear from students who find it hard to take breaks because they feel guilty if they do – the statement ‘I should be working’ is uttered very frequently. But the truth is taking a break is not a bad thing and can actually enhance your overall productivity.

Why is it important to take breaks? There are many reasons, all of them generally answered by the comment ‘because they enhance your learning’. Some explanations are as follows:

- This one is very important – NO-ONE can physically study all the time. EVERYONE needs to battle exhaustion at some point, to recharge their battery, so that they are fit to continue their work productively.

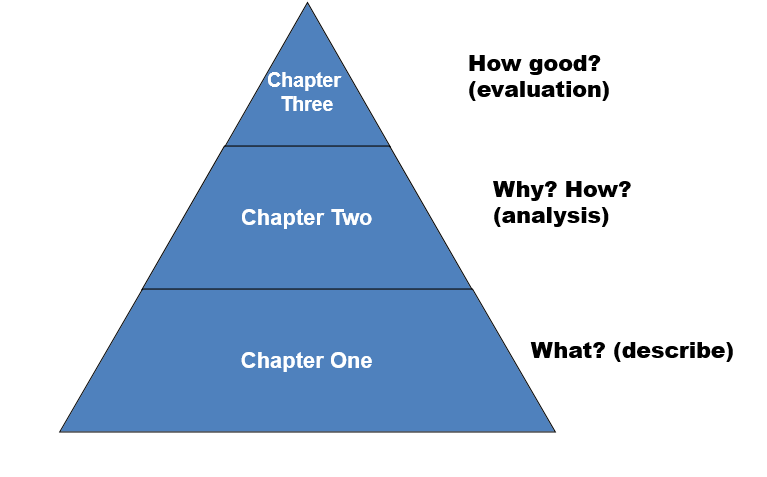

- Many students come to the WDC because they can no longer really see what they are trying to say; they have lost sight of their focus and feel out of control of their material/reading. They no longer have their own academic voice and are allowing others to speak for them. They can’t, as the saying goes, see the wood for the trees. It is at this point that a break could really help to refresh sight of the work, to allow a view of the topic from a different angle, to encourage approaching the same material in a different way, so that, ultimately, clarification of ‘what is my overall point anyway?!’ can be achieved.

- This one is also important – when charged with a task to do, we often focus on the writing part (well, obviously…) but what we often forget is that whatever words are on a page must also, eventually, be read. This therefore means that we should at least give some time to think about how a reader might look at, indeed interpret, our work. A break allows us to change shoes, to step into those of the reader and approach the text as them. This can sometimes be a real eye-opener, and lead you spot things you wouldn’t have otherwise noticed.

- Lastly, just as a little aside, breaks allow us to enjoy eating (and see food as more than just a necessity of the day!) and to get some exercise, even if that just constitutes a little walk round the library floor. A healthy body is a healthy mind and all that….

So here are some reasons as to why stops in study are good. But how do you kick guilt to the curb and set in place a breakin’ routine? Here are some strategies you could try:

- Schedule a break and stick to it. That means break at the time you intended to break AND return to work at the intended end time. Breaks do work better if you neither skip nor lengthen them….

- Here we must reference Monty Python: ‘And now for something completely different’. Plan something to do in your break that makes you think about something else. Something that allows creativity, movement, relaxation, a change of scenery, maybe…. For me, a dance class was great for this – you have to stop thinking about your work to make sure you put your feet in the right place to avoid falling on your face. Dance doesn’t work for everyone, but the idea is that a break should be a real shift for you, taking you away from the work to allow you to come back refreshed. What would do that for you?

- If you are really worried about how a break might affect your work, there are a number of ways to manage your concerns. For example, you could identify where to pick up from in your work before you take a break, so that you know exactly where you are coming back to. You could even try taking a break mid-way through a sentence, so that the transition back into your work is easier – you will have to finish that sentence!

There is no set length for a break time and there is no prescription as to what you should do in one – it’s up to you to think about how break might work best for you. The important thing is to try and take them and, ultimately, give yourself a break for breaking…

posted by Heather