I wrote in my last post about the mining explosion of 1757 that killed 16 men at the Ravensworth Ann Pit, which formerly occupied the site where The Angel of the North now stands. All 16 of the men were buried in the churchyard of St Andrews’ Church in Lamesley on 12 June 1757, and this weekend I walked to the village to see if there was any surviving trace of the burials.

The Angel of the North is in the parish of Lamesley and its silhouette was clearly visible behind the church, as I looked across from Lamesley Pastures. The Pastures are an area of farmland that has remained undisturbed by mining and that is now being managed by the Durham Wildlife Trust as a winter water meadow, using medieval methods of flooding the fields in winter to provide a habitat for wading birds such as curlew, lapwing, redshank, and snipe. Exmoor ponies grazed in the surrounding fields, which helps wildflowers to thrive.

The village also houses the ruins of Ravensworth Castle, former seat of the Liddell family. Barons of Newcastle, the Liddells occupied the estate for over 300 years, much of their fortune coming from coal mining on the land. Walking round the churchyard, I found tombs and gravestones dedicated to various members of the Liddell family. Although not buried in Lamesley, Alice Liddell, the model for Alice in Wonderland, was a relative of the Liddells of Ravensworth and the village pub, The Ravensworth Arms, is where Lewis Carroll is reputed to have written parts of the book.

Although I searched carefully among the graves, I could find no memorial to the mining accident of 1757, and neither did I see any individual graves for the men listed on the Durham Mining Museum website. It could be that, unlike the Liddells, the miners’ families could not afford to mark the burial site, or the stones might either have disappeared over the years or weathered to make the writing illegible. There was one communal grave in the cemetery, now planted with wildflowers, which marked an outbreak of cholera in 1848-9 that claimed the lives of 120 people in the neighbouring village of Wrekenton. In his paper, ‘On the Mode of Communication of Cholera’ (1855), Dr John Snow reported that the disease was particularly virulent among the mining communities. He wrote as follows:

The mining population of Great Britain have suffered more from cholera than persons in any other occupation; a circumstance which I believe can only be explained by the mode of communication of the malady. Pitmen are differently situated from every other class of workmen in many important particulars. There are no privies in the coal pits, or as I believe in other mines, the workmen stay so long in the mines that they are obliged to take a supply of food with them, which they eat invariably with unwashed hands and without a knife and fork.

Snow also reported that, once contracted, cholera spread among the mining community faster than in any other occupation, due to the working conditions underground.

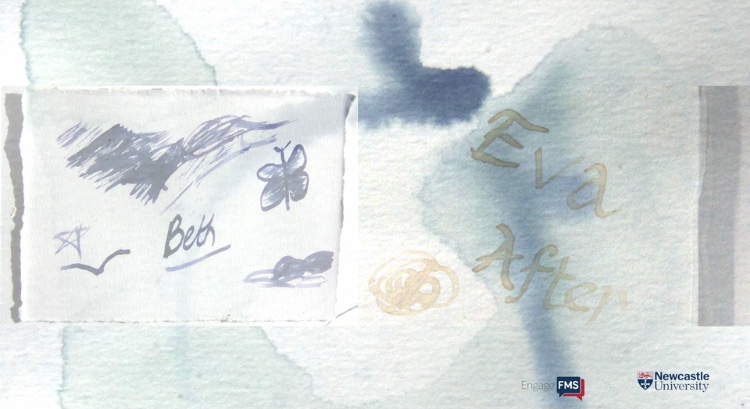

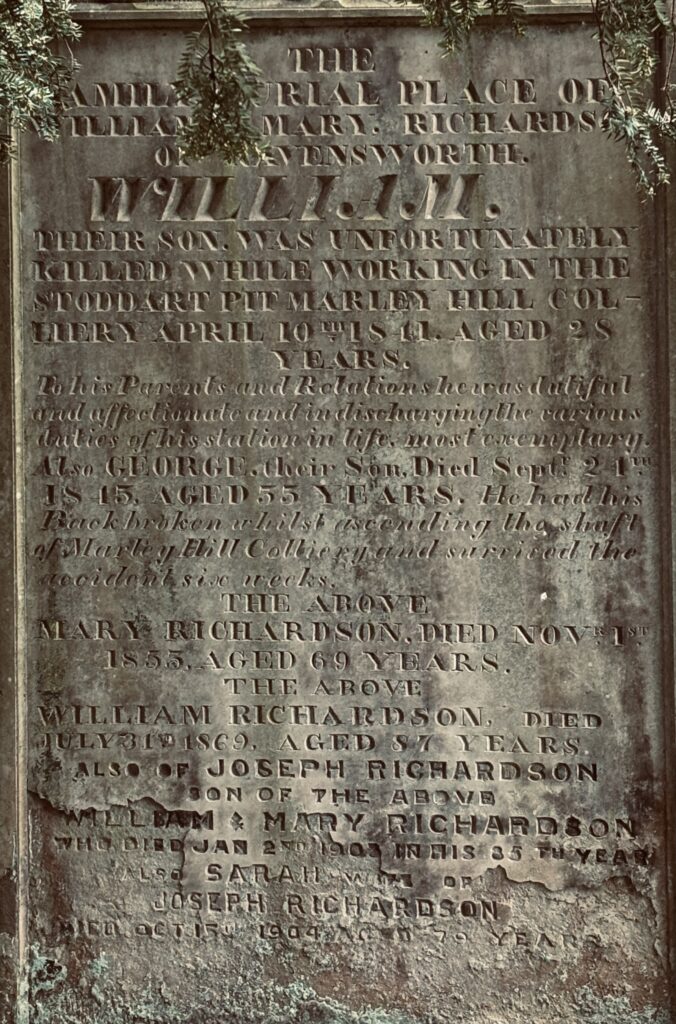

Even though I could find no trace of the miners killed in the explosion, other headstones in the churchyard commemorated individual miners whose lives were lost in the surrounding collieries. William and Mary Richards of Ravensworth lost one son, William, aged 28, in 1841, when he was working at the Stoddart Pit of Marley Hill Colliery. A second son, George, died in 1845 after an accident in the same colliery that broke his back when he was coming up the shaft. Although George survived the initial impact, he died six weeks after the injury.

A second headstone also commemorates two lives lost from the same family, although the exact relation between the men is not clear. George Steel died at Newbottle Colliery in 1821, aged 28, and Charles Steel died at Springwell Colliery in 1840, aged 55.

Walking through the graveyard in Lamesley gave me a different perspective on The Angel. Not only was I seeing the sculpture itself from an unaccustomed viewpoint, but reading it in relation to the gravestones in the cemetery offered a new sense of it as a memorial to the coal industry. Coal mining employed many men across the region, and it also generated substantial profits. The Liddells as landowners had mined coal on their estate since the early seventeenth century, and their profits enabled them to demolish the original castle in 1808 and to commission the foremost architect of the day, John Nash, to build a grand house for them in the Gothic Revival style. How do the ruins of Ravensworth Castle relate to The Angel that now rises on the hill above them? How, too, do we position The Angel in relation to the largely agricultural landscape of Lamesley? Lamesley Pastures reminded me that farming also takes place in the shadow of The Angel, and that it is important to consider the diversity of employment in the surrounding area, both historically and in the present. Does The Angel risk projecting a monolithic history of the North, based in the decline of heavy industry, and occluding alternative stories and identities?

References

Northumberland Archives, ‘The 1848-9 Cholera Visitation’, 16 May 2017, https://www.northumberlandarchives.com/2017/05/16/the-1848-9-cholera-visitation