Posted by Andy Pike, 3 June 2013

Growing recognition of the role of institutions in academic and policy circles has invigorated discussion about what they are, how they work and what they might bring and detract from effective local and regional development. Simplistic arguments that institutions are necessarily bureaucratic hindrances to the free and fair operation of the market economy have been questioned. Similarly, the case for institutions as a kind of ‘magic dust’ capable delivering successful economic development in any circumstances has been challenged.

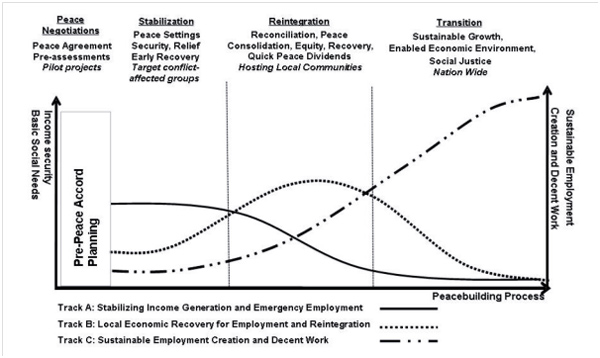

In defining institutions, many studies fall back upon Douglas North’s idea of institutions as the ‘rules of the game’ within a society that shape how actors – public, private and civic – relate and behave. Making this a bit more concrete, we can identify two main types of institutions – formal and informal (Figure 1). Formal institutions are ‘hard’ or codified, typically written down and documented. They include things like charters, constitutions, laws, regulations, rules and requirements. They are manifest in contracts, legal statutes and property rights. Informal institutions are ‘soft’ or tacit, often existing in the minds and practices of the actors involved rather than being formalised and codified. They include things like conventions, habits, norms, routines, traditions and values. We see them manifest in phenomenon like trust, social capital and networks.

Figure 1: Types of institutions

|

Formal ‘Hard’ – Codified

Charters, Constitutions, Laws, Regulations, Rules, Requirements

e.g. Contracts, Legal statutes, Property rights

|

Informal ‘Soft’ – Tacit

Conventions, Habits, Norms, Routines, Traditions, Values

e.g. Trust, Social capital, Social networks

|

Defining institutions and distinguishing their different kinds only brings us so far. Integral to the debate has been the question of their role and contribution to development regionally and locally. As countries across the world wrestle with the challenges of economic development, particularly in the wake of the global financial crisis and in some countries state austerity, questions of institutional design, purpose and contribution have come to the fore.

In theory, institutions can play a positive role in providing public goods, addressing ‘market failures’, reducing uncertainty, reducing transactions costs, promoting efficiency and tailoring policy to regional and local contexts. These potential roles are manifest in a range of things institutions actually do on the ground:

- diagnosing and interpreting regional and local economic growth issues

- leading and decision-making

- formulating strategy and priorities to articulate courses of action and paths of development

- providing voice for regions and localities in multi-level and multi-actor systems of government and governance

- co-ordinating, integrating and mobilising actors to facilitate dialogue and negotiation

- fostering linkages between public, private and civic sectors

- generating, pooling and directing resources

- setting the framework and incentives that shape the individual and collective choices and behaviours of economic actors.

But the role of institutions is not always and everywhere positive. There are a number of potentially negative contributions institutions make that can inhibit local and regional development. These include: unfunded mandates when they are given or accept responsibility without resources; bureaucracy, lock-in and sclerosis hampering flexibility and responsiveness; duplication and fragmentation stimulating competition for resources; capture by elite actors and rent-seeking by particular interest groups; and, corruption. Indeed, recent work by the OECD on Promoting Growth in All Regions identified a number of ‘institutional bottlenecks’ that can trap regions and localities in low growth trajectories:

- poor mobilisation of stakeholders

- lack of continuity and coherence in the implementation of policies by institutions

- institutional instability

- lack of a common and strategic vision

- lack of capacity

- gaps in multi-level governance frameworks.

Central to shaping institutions for local and regional development, then, is a sharper understanding of what they can and can’t do as well as moulding their features to work effectively within particular regional and local contexts.