Stefan McElwee George Stephenson High School

It is a widely held belief amongst professionals in a wide spectrum of professions that we continue to learn during our working lives. Learning is a continual process of development linked to professional and social context, both within and outside of the workplace environment. It might be viewed that this is a challenging assertion which stimulates further investigation within the busy school environment. Can we assume teachers learn or do we need to investigate carefully what conditions exist or can be created to facilitate authentic professional learning?

This blog summarises the thinking and feelings of a Leadership team in a secondary school in Newcastle-upon Tyne on professional learning. As an Assistant Head Teacher with a responsibility for learning in school, I wanted to probe the subject further. The rest of the team agreed and so we read. The reading process alone was wholesome as our agendas often focus on the routine or strategic management of the day to day operational material which demands much of our time. Through reading academic research findings on the subject we uncovered a stimulus, a developing need to reflect on this important, yet often neglected subject.

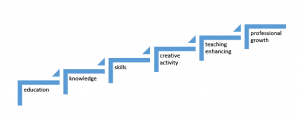

The first challenge was to establish the clear difference between the traditional didactic delivery of content which is common in CPD environments, and the potential to create alternative environments in the workplace that allow authentic professional learning to flourish. The work of Ann Webster-Wright (2009) summarises this distinction and argues for a conceptual change towards a new form of professional learning based on two decades of research across professions. This article was introduced to me through my participation in modules related to coaching and mentoring for teacher development, in the School of ECLS, at Newcastle University.

As a leadership team, our conversations quickly turned to our “performativity” agenda, and our role in ensuring professional standards, accountability of practice and the creation and monitoring of measurable outcomes. Our ownership of “knowledge” linked to standards inevitably influences what we determine to be of value and justifiable to learn for teachers and other colleagues in our school context. We feel these pressures place a huge constraint on learning – both that of teachers and our schools’ students. The uncertainty and pace of educational reform produces a high-stakes environment in which colleagues often tell us they have no time to learn. The challenge for us was fairly clear in our discussions. We want to devolve this knowledge ownership and to provide an infrastructure for teachers to take ownership of their own learning in an environment which supports authentic professional learning.

This key aim led our thinking to the consideration of the contextual factors that make our school a unique place of learning for those operating within it. We have considered the importance of context to the learning of our pupils for years but have never really reflected on it for the learning potential of our staff. How well do we create and support a learning culture in our school? We feel we are establishing an environment supportive of authentic learning as established through research findings. We strongly believe in communities of enquiry. Our staff learn together in collaborative groups where teacher talk draws on critical reflection based on experience. We are comfortable and confident in our teachers as participants and not spectators in the learning process. Much of what staff tell us reflects the notion that teacher ownership of a hunch or problem is essential to actively engage professionals in working on genuine problems. We discussed the crucial component of ensuring our teachers have time to reflect on their problem-solving to transform experience into learning.

We feel strongly that our action research cycles meet many of the criteria of authentic professional learning, but there are areas we need to probe further. Our thinking takes us towards the purpose of learning. Should it be represented in activities that are amenable to outcomes? What do we count as legitimate knowledge? Do teachers have a say in this and how do we justify our decisions in a standards-driven framework?

We have concluded that teacher ownership of learning is a key component, some needs to be negotiated yes, but authentic learning challenges leadership structures to consider the “lived experience” of our colleagues. The social complexity of their position in the workplace potentially drives their assumptions of practice and how they “feel” about their own learning. We are considering sociocultural factors very carefully. Our follow-up work will now focus on establishing how we can involve our teachers in the learning process and how we can further exploit the supportive contextual factors that have allowed the first tentative steps in authentic professional learning to occur in our school.

Reference:

Webster-Wright Anne, Reframing Professional Development Through Understanding Authentic Professional Learning. Review of Educational Research. 2009 79: 702 published 25 February 2009.

Stefan McElwee is Assistant Headteacher and George Stephenson High School which is a Teaching School with both ECLS and CfLaT (Newcastle University) as strategic partners. Stefan is currently completing the M.Ed in Practitioner Enquiry (Leadership) programme at Newcastle University.