I was tempted to begin this blog post with a witty anagram of BERA and BELMAS, the two conferences I attended this summer but it is with some degree of embarrassment that I have given up with nothing to show for my efforts.

BERA stands for the British Educational Research Association. According to their website (www.bera.ac.uk), it is a ‘membership association and learned society committed to working for the public good by sustaining a strong and high quality educational research community, dedicated to advancing knowledge of education’. BELMAS is also concerned with the field of education but this society focuses on aspects of and issues concerning leadership, management and administration.

I have been trying for some time to identify ways of applying the methodological and analytical approaches, which I used in my doctoral work, to contexts of educational leadership in line with my roles and responsibilities within the North Leadership Centre. My doctoral work was a study of teachers’ developing understanding of enquiry based learning. It primarily concerned concepts of identity and agency in relation to curriculum innovation and formative assessment. My current position within the North Leadership Centre allows me to work with serving school leaders on aspects of their personal and professional development including identity and agency.

I was delighted, therefore, that my first solo abstracts for both BELMAS in July 2016 and BERA in September 2016 were accepted and included in the conference proceedings. The abstracts presented the rationale and outlines for two different workshops:

How can Bernstein’s (1996) concepts of ‘classification’ and ‘framing’ be used to explore the development of programmes for school leaders in the North East of England?

This workshop addressed the theme of the 2016 BELMAS conference by challenging a shift in government oversight of education from compliance to performance (Ball, 2000) with a more ‘humanist’ approach to professional leadership development. It offered tasks aimed at identifying underlying issues which enable or discourage leadership curriculum innovation. The discussion considered whether incorporating the development of ‘weak’ social structures in new leadership development programmes can help to address key priorities in improving the leadership and management of schools in the current Education sector.

Our dialogical selves: developing an analytical framework for exploring practitioner identity and agency.

This workshop introduced the concept of the ‘dialogical self’ (Hermans, 2001a; Hermans, 2001b) and invited participants to engage with a developing analytical framework for exploring themes of identity and agency. It offered practical tasks aimed at uncovering underlying issues which enable or discourage practitioners to ‘act’ within their particular contexts. The discussion considered whether the analytical framework I employed as part of my doctoral work can help to address key priorities in developing practice in the current Education sector.

Both workshops were designed to foster dialogue and encourage critical reflection in order to seek out whether my ideas for future work would stand up to the rigour and expectations of the academic community. For the first time at these conferences, I felt like I was beginning to find my feet as an academic, capable of holding my own in discussions with others for whom I have a very high regard. That other academics were prepared to share their experiences and expertise with me was a huge boost to my confidence. That they encouraged me to continue with my approaches will be the motivating factor moving forwards.

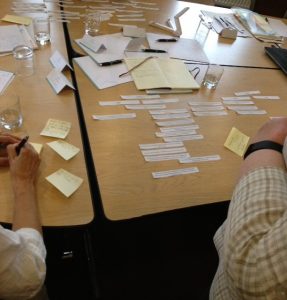

Image: Outcomes from the BELMAS 2016 workshop

Moving forwards, then, I have committed to preparing and submitting an article for a special issue of ‘Management in Education’ later this year. When I reflect upon my experiences at both BELMAS and BERA, I now realise that I engaged in the conferences as a personal and professional learning opportunities, where, by providing stimuli for discussion, the responses of academic colleagues helped me to move forwards with my own my thinking and doing. Ironically, I feel I am undergoing a shift in identity myself, which is compelling me to engage further and with greater self-belief.

Dr Anna Reid is a Lecturer in Educational Leadership, Deputy Director of the North Leadership Centre and Programme Director for the North East Teaching Schools Partnership (NETSP) within the School of Education, Communication and Language Sciences at Newcastle University.

Twitter: @AjrReid

References

Bernstein, B. (1996) Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity. Maryland: Rowman and Little Publishers, Inc.

Hermans, H,. (2001a) ‘The dialogical self: Toward a theory of personal and cultural positioning’, Culture & Psychology, 7(3), pp.243-281.

Hermans, H. (2001b) ‘The construction of a Personal Position Repertoire: Method and practice’, Culture & Psychology, 7(3), pp.323-365.

Reid, A. (2016) ‘Aspiring leaders understanding their ‘selves’ and/in social contexts’ [Online] Available at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog/aspiring-leaders-understanding-their-selves-andin-social-contexts. Accessed on 16 August 2016.

Reid, A. (2015) ‘An opportunity for change‘ [Online]. Available at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog/an-opportunity-for-change. Accessed on 16 August 2016.