In a recent issue of Nature the discovery of a new family of proteins that store copper ions inside bacterial cells was reported. This work was carried out by Prof. Chris Dennison’s lab (ICaMB) in collaboration with Dr. Kevin Waldron (ICaMB), Dr. Arnaud Baslé (ICaMB), Dr. Neil Paterson (Diamond Light Source) and Prof. Colin Murrell (UEA). Here, Kevin tells us about this discovery and what its implications could be for the biotechnological exploitation of methane.

Methane, the main component of natural gas, is produced by both geological and anthropogenic processes on Earth, and can be released into the atmosphere. The biosphere’s primary mechanism for limiting the amount of methane (a powerful ‘greenhouse gas’) that escapes into the atmosphere is through its consumption by methane-oxidising bacteria, or methanotrophs (literally ‘methane-eating’), who utilise methane as both a carbon and energy source.

Transmission electron micrograph of a M. trichosporium OB3b cell showing the intracytoplasmic membranes that house the copper-dependent enzyme pMMO.

The key enzyme that methanotrophs use to oxidise methane to produce methanol is called methane monooxygenase (MMO). Almost all methanotrophs possess a membrane-bound form of MMO that requires copper (Cu) for activity, called pMMO (some strains also possess an iron-requiring alternative soluble enzyme, called sMMO). Therefore, these bacteria have an unusually high demand for copper, a metal that is essential for most organisms but is used rather sparingly, mainly because it can also be extremely toxic.

Previous studies of methanotrophs have revealed that they utilise unusual mechanisms for acquiring the copper they need for pMMO. For example, they produce and secrete a small, modified peptide called methanobactin that is involved in high affinity copper uptake, analogous to the more familiar siderophore iron uptake systems.

The model methanotroph, Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b, was analysed in the hope of uncovering novel copper proteins. Soluble extracts were resolved by two-dimensional liquid chromatography, with the copper content of resulting fractions monitored. The most abundant copper pool was found to contain a small, cysteine-rich protein that had not been studied previously and Chris Dennison (PI) and I (Co-I) obtained a BBSRC grant to investigate this and related proteins.

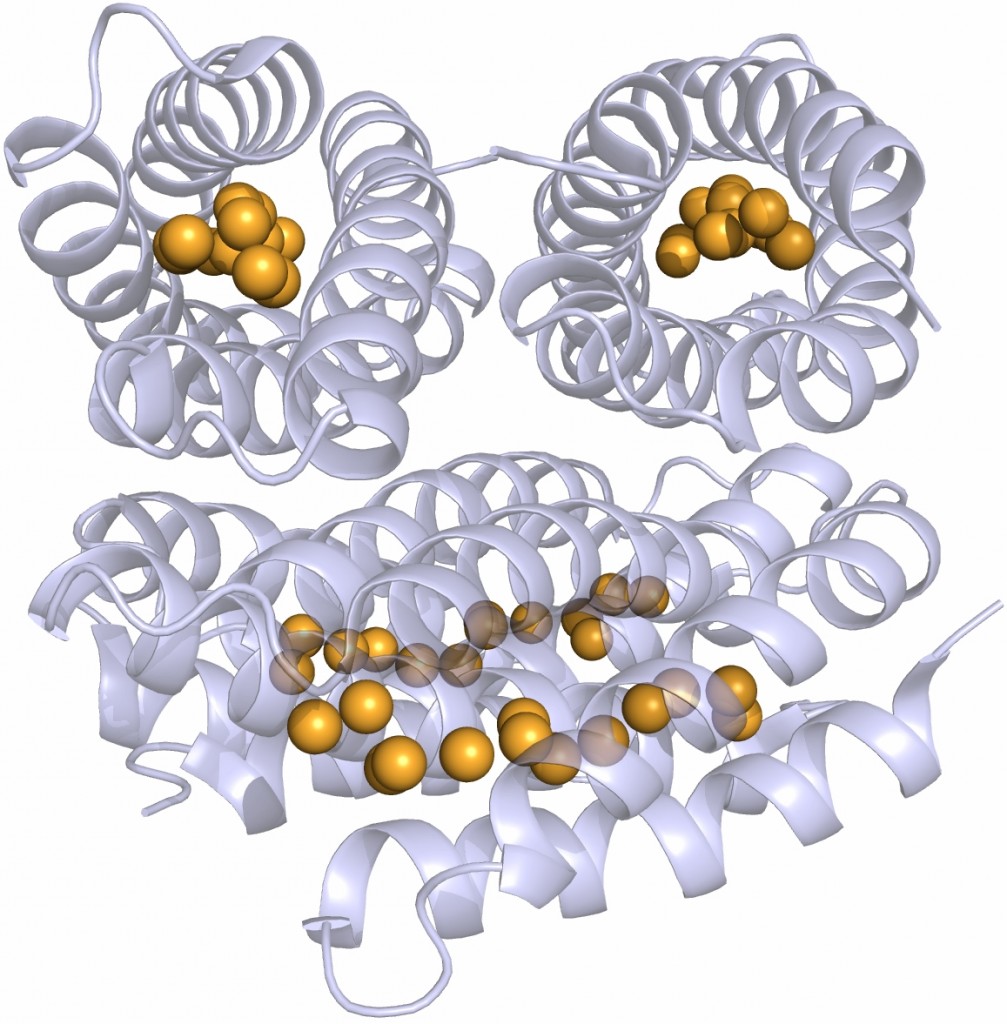

The presence of 13 cysteine residues in a mature protein (after cleavage of its signal peptide) with only 122 amino acids was immediately significant, as its thiol sidechain is often found in copper-binding sites. The recombinant protein was extensively studied using a suite of biochemical and biophysical methods to determine its in vitro properties This novel tetrameric protein is capable of binding up to 52 Cu(I) ions with high affinity, consistent with a potential role in the storage of this essential metal and was therefore named Csp1 (copper storage protein 1). A mutant strain of M. trichosporium OB3b that lacks this Csp1 protein (as well as a closely-related protein, Csp2) shows a phenotype consistent with a copper storage role of these proteins in vivo.

The crystal structure shows that the apo-monomer adopts a well-characterised four-helix bundle motif with all 13 cysteine sidechains pointing into the core of the bundle. The protein structure is essentially unchanged in the presence of copper, except that the core of each monomer has filled with 13 Cu(I) ions, bound by the cysteine sidechains. This is an unprecedented structure for metal storage.

The structure of the Cu(I)-Csp1 tetramer, with the 13 Cu(I) ions bound within the core of each four-helix bundle shown as orange spheres.

The implications of this discovery could be of wide impact. There is a great deal of interest in using methanotrophs and MMOs in industrial biotechnology. Available methane is on the increase due to ‘fracking’, but importantly methane can also be produced from sustainable sources such as through the degradation of biomatter (biogas). Methanotrophs and the MMOs could in future be exploited using synthetic biology approaches for gas-to-liquid conversion, for the production of liquid fuels as well as bulk and fine chemicals from renewable methane.

Any such biotechnological applications require an understanding of how the production of pMMO is regulated and how this complex enzyme is assembled, including the cellular delivery and insertion of the essential copper cofactor. The work published in Nature shows that Csps are an important piece in that assembly jigsaw.

Furthermore, bioinformatics has shown that cytosolic members of the Csp family are also encoded in other bacterial genomes. Most bacteria are thought not to require copper in their cytoplasm, so the presence of cytosolic Csp homologues in their genomes could re-write our basic understanding of their use and homeostasis of copper.

Links:

Nature article: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v525/n7567/full/nature14854.html

News & Views: http://www.nature.com/nchembio/journal/v11/n10/full/nchembio.1918.html

BBSRC website: http://www.bbsrc.ac.uk/news/fundamental-bioscience/2015/150827-pr-bacteria-that-could-protect-our-environment/

ACS Chemical & Engineering news: http://cen.acs.org/articles/93/web/2015/08/Protein-Stores-Copper-Methane-Digesting.html

Press release: http://www.ncl.ac.uk/press.office/press.release/item/could-bacteria-help-protect-our-environment