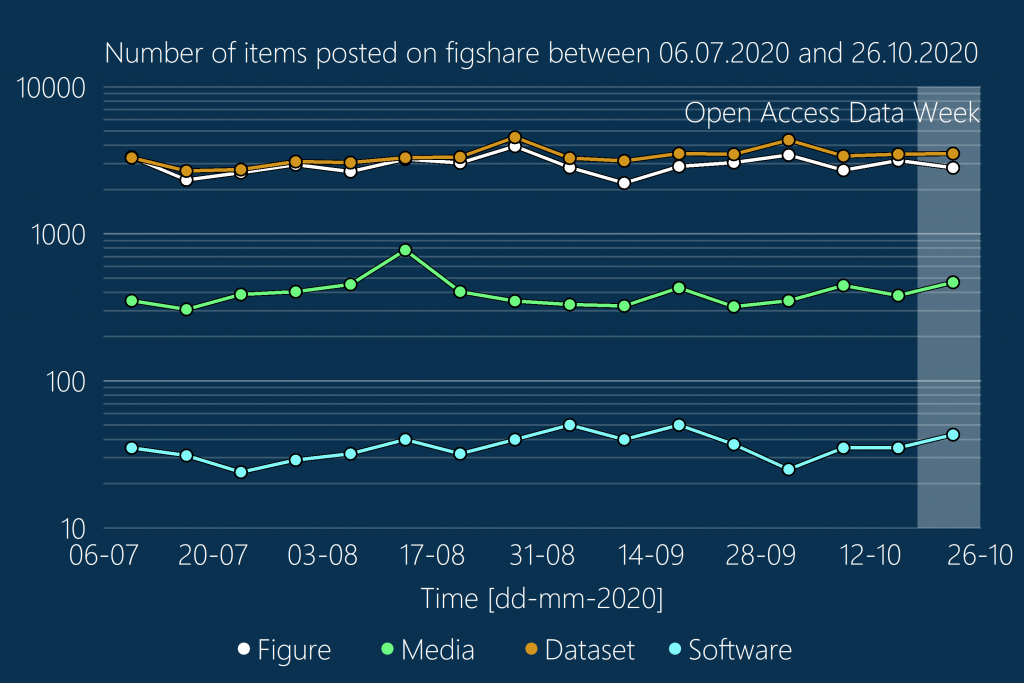

To researchers’ credit across the globe the amount of data being shared is growing and this will only increase over time as open research becomes ubiquitous. There are significant benefits to data sharing including increased rigour, transparency, and visibility.

But this post isn’t going to get blogged down in the benefits of data sharing as it is a path well-trodden. Instead, let’s consider that as researchers have been archiving and sharing data in archives and repositories there is a rich source of material that can be accessed, reworked, reanalysed and compared to recent data collections.

This secondary data analysis is a growing area of interest to researchers and funders, with the latter having calls focusing solely on reanalysis of data (e.g. UKRI). Accessing historic data also allows for research to be undertaken where costs are prohibitive, data is impossible or difficult to collect, and, possibly, reduce the burden on over researched populations. With the continuing challenges with collecting primary data during the pandemic there might not be a better time to consider what data is already out there.

And it is not only research that can benefit but also teaching and learning. Archived data sources can be accessed to introduce students to a fantastic range of existing data and code. Using secondary data can free students of data collection allowing them to focus on developing skills of research questions and analysis.

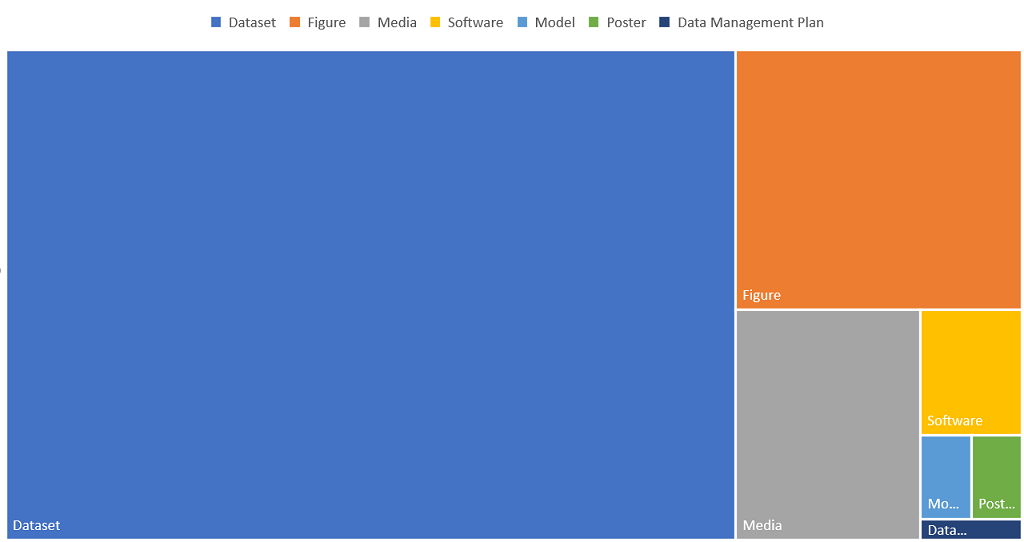

Based on data from re3data.org as of April 2021 there are over 2600 data repositories available for researchers to archive data, up from 1000 in November 2013. This isn’t a completely exhaustive list but is close enough to give an idea of the scale. Amongst these is our own data.ncl that now houses over 1200 datasets shared by university colleagues from across all disciplines and collected using a variety of methods and techniques.

However, finding the right dataset for your latest research project or teaching idea isn’t always straightforward. To help with that I have created guidance on how to find, reuse and cite data on the RDM webpages.

I would also be very keen to hear from users of secondary data to create case studies to inspire colleagues on this approach. If you would be interested in sharing your approach and experience, then please do get in touch.

Image Credit: Franki Chamaki on Unsplash