August 11th 2020 marks the 40th anniversary of the Tyne and Wear Metro. In this Lug Post, Andy Clark confesses to his enthusiasm for all things railway-related and discusses a new oral history project that NOHUC are supporting on forty years of the Metro.

Many people have a hobby or an interest that they aren’t particularly vocal about due to social perceptions. My own is almost too embarrassing to talk about publicly, as those with an interest are frequently ridiculed. But today, I feel that I have good reason to speak about my dark secret openly. On the 40th anniversary of the Tyne and Wear Metro, I feel able to say: My name is Andy Clark, and I am a train enthusiast.

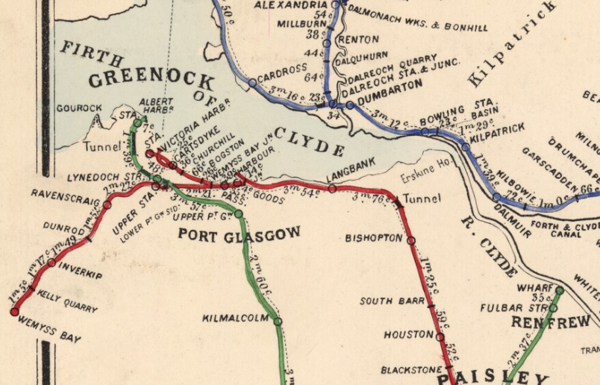

As oral historians, we are interested in how people develop hobbies and fascinations. For me, there are a few reasons, all bound up in childhood memories and upbringing. I was brought up in Greenock, a town with a disproportionate number of train stations. Between two lines, there are eight stations in a town of c.58,000 people. Add to this disused railway lines that still cut through the town, the geography of Greenock is fundamentally shaped by trains and the railway. Family is a key influence also. My granda followed a stereotypical path of the Irish migrant in Scotland by working on the railway from the time he arrived until his retirement, latterly being the station master at the famously stunning Wemyss Bay station. As weans without private transport or trips abroad, trains were synonymous with holidays away. We took the West Highland Line when camping in Oban, the West Coast Main Line to Preston before heading onwards to Blackpool, and even a day up to Glasgow began with a train journey. As we became older, a major marker of our independence was being allowed to get on the train ourselves, whether short journeys to Cappielow Park and the football, or longer trips to exotic places like Port Glasgow, Bogston, or Largs.

As I’ve got older, I’ve actively chosen to live in places with good train links and easy access to the railway network and I’ve always lived within walking distance of at least two stations. When moving to Newcastle in 2017, this opened up a whole new world of rail travel that I was almost completely unaware of previously – the Tyne and Wear Metro System. Now, in its 40th year, I am fortunate enough to be involved in a new oral history project of the Metro, 1980-present. I’m sure you can understand the sheer excitement that I have at the prospect.

‘The Metro’, as it’s known locally, is a fascinating system, demonstrative of ambitious urban planning, integrated public transport, and the possibility of reusing abandoned lines for new ventures. The network was constructed after the passing of the Tyneside Metropolitan Railway Act (1973), and officially opened on August 11th 1980, with a single route operating from Haymarket in Newcastle city centre to Tynemouth on the coast. Much of this first phase of Metro track and stations utilised infrastructure that had lay abandoned following successive cuts to railway services, and stations such as Tynemouth and Whitley Bay were repurposed as Metro stops. A series of expansions have been carried out since, with a £12m extension to Newcastle International Airport completed in 1991, and a £100m project linking Tyneside and Wearside opened in 2002. In April 2017, Nexus took direct control of the system, placing it fully in public ownership as had been envisaged when it opened. Future expansion is planned, and new rolling stock is currently being built by Swiss firm Stadler to replace the ageing fleet that has operated since Metro’s inception.

When I first moved to Newcastle, my enthusiasm for all things railway meant I gravitated towards the Metro. I was fascinated with the system, and felt more than a pang of jealousy that Glasgow – the city where I lived previously – has never expanded its subway service, never mind with the type of ambition shown by Metro. When I lived in a houseshare, my flatmates found it odd that I took a longer journey to work than was necessary. Despite there being a bus stop right outside the door that dropped me off at the University, I opted to walk 15 minutes to Chillingham Road Metro, and jump the train to Monument in the city centre, before walking another 15 minutes to the office. I immediately noticed how busy the service is, despite good bus routes; clearly many others also prefer commuting by light rail than by road.

I also quickly became aware of the centrality of the Metro to the city and the wider region. Trains filled with barcode clad Geordies are synonymous with Newcastle United matches at St James’ Park, whilst at the other end of the network Mackems pile on to head for the Stadium of Light. Both stations are decorated in the colours of the respective teams, and many other stations have some form of public art on display. On sunny days, metros heading for Whitley Bay and Tynemouth are packed with families heading for a day on the beach and, in the evenings, people heading into the city for a night out pile on with their thinly disguised carryouts to get them on their way. Culturally, the Metro has been the scene of murders for Vera Stanhope to solve, and a memorably ridiculous chase by Jimmy Nail in Spender. In only 40 years, the Metro has become integral to life on Tyne and Wear, and is a system that should be replicated across the UK (I’m looking at you again, Glasgow).

This new oral history project, in which NOHUC are supporting Remembering the Past, Northern Cultural Projects, Nexus, and TWAM, will go beyond the interests of railway enthusiasts like me to examine the multiple impacts of the Metro on the people, economy, and landscape of Tyne and Wear. There is much to learn and to analyse, and interviews with Nexus staff, local politicians, and passengers will be conducted to interrogate the influence of the Metro, and how the development of the system is remembered by those who use it most. Some areas for investigation include: the physical impacts of the Metro system on the region; the economic influence of light rail on employment and industrial location; working for the Metro and changes in employment over 40 years; the tensions between public and private ownership and integrated transport; and how Metro journeys are remembered across generations over the last four decades.

We are beginning the process of recruiting interviewees and will be conducting these over the coming months, whilst exploring a number of possibilities for interactive outputs. We will update The Lug frequently during the research process, but for now, all that remains to be said is:

Happy 40th Birthday to the Tyne and Wear Metro!

Happy B-day to Metro! How could I missing so important anniversary?