Suzanne Butler is a first year Sociology PhD Student at Newcastle University, researching the emotions of women in poverty throughout the life course. In this post, Suzanne calls for a new feminism for disadvantaged women.

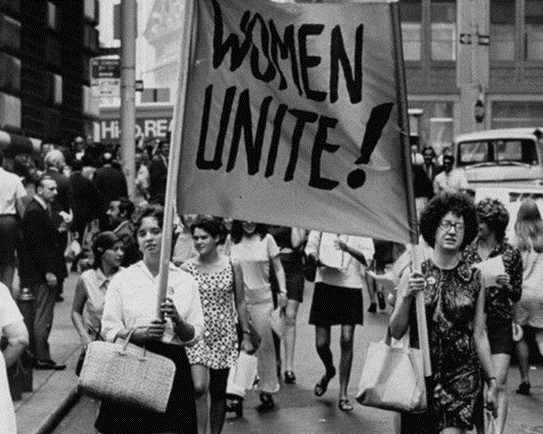

Let me ask you a question: can you think of a feminism for the disadvantaged woman? I do not mean Black feminism or Islamic feminism, which undoubtedly take into consideration the marginalised, gendered experiences of those groups, and should be applauded for doing so. I mean a broad sweep of feminism for each and every disadvantaged woman. I cannot think of one.

What of the woman who must make impossible choices under impossible constraints simply because she is a woman with precious little money? She might be single or in a couple, but she will be responsible for the welfare of the family and the caring of children (Pew Research Centre, 2015). Sometimes she has to make a bag of potatoes last several days, stretching them out over various meals and for multiple family members. The woman who hides brown envelopes under her sofa cushion because she cannot pay the bills, and she cannot bear to look at them. And the woman whose daughter hides letters from the school because she does not want to put any more strain on her mother by asking for money for school trips. The woman who has so much weight bearing down on her to keep a roof over her children’s heads and food in their stomachs that she has no remaining energy to care for herself or contemplate how she might want her life to be.

These women are caught in the crossfire. Facing entangled social challenges like a punitive welfare system, stigmatising discourses and low paid, insecure employment. At the same time, there is an expectation for her to be a shining example of motherhood, raising the future ‘good citizens’ of our society; future workers and taxpayers. Disadvantaged women are positioned as both the cause of society’s problems by being welfare dependent, and the solution, by bearing the responsibility to bring up the next generation. These women have been left behind and they are just about surviving.

Where to next for disadvantaged women’s feminism?

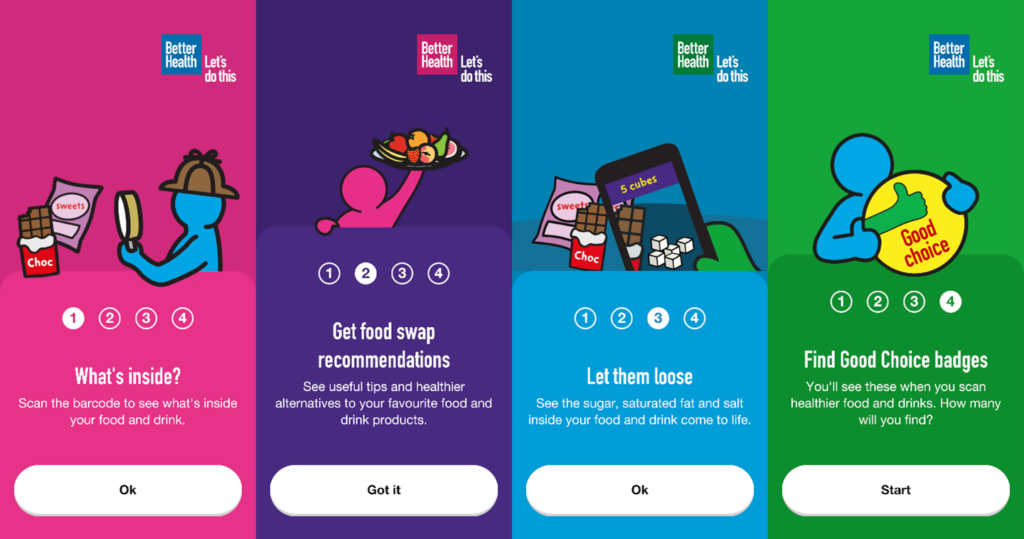

Feminism has made some fantastic inroads for women, from voting, to divorce and abortion rights. A male-dominated political and corporate world is slowly becoming a thing of the past. Women are increasingly occupying higher status and more powerful positions in the public sphere. They are demanding respect, dignity and acknowledgment. Women are slowly gaining seats at the metaphorical table. But mostly these are women that already have the status, resources and capitals afforded to them by their position in life (IPPR, 2013). Feminism is, by and large, a middle-class pursuit. It is harder to raise your head above the parapet in this way when you are already the subject of much of the world’s vitriol. The narratives of ‘benefits scrounger’ have been hard to escape in the media.

To demand equality requires considerable resources, time, money and energy, of which disadvantaged women have very little. Moreover, with whom exactly would they be demanding equality? Disadvantaged men? Somehow this hardly seems worth the effort, and anything more than this looks like an elaborate fantasy, especially under current conditions.

After more than 10 years of austerity, of which women bore most of the brunt through cuts to services and benefits (The Socialist Review, 2020), came a global pandemic. This meant almost a year of home-schooling, with many juggling being a keyworker and a parent. Now we have a cost-of-living crisis, forcing women to choose between warmth or food for their children – and enough is enough. There is an urgent need for a policy response to this. The Equality Act 2010 does not include socio-economic status as a protected characteristic – while not a panacea, the inclusion of this would be a significant step in the right direction to address the intersection of disadvantage and gender for women. Like with any dramatic shift in attitudes towards and resource allocation for women, the push must come from women themselves. From us – if you are a woman reading this – and from others around you. We must include disadvantaged women in the policy changes we demand, and highlight their experiences of being marginalised.

I recently went to a social sciences networking event where the keynote speaker was a recent author of a feminist text. A member of the audience asked about classed intersectionality in her book, and the ways she had included working-class women’s experiences in there. The author replied that while she had read extensively on the subject, she had not found this in the literature and therefore had not included this dimension of women’s experiences. What is the state of a body of intellectual work that excludes such a large group of people in this way? It is now time to develop this work, grow this voice, and demand acknowledgement of disadvantaged women in feminism. If they are absent from this debate their experiences and issues are made invisible, and there cannot be any formulated response. So here I set a challenge to women: let us include our disadvantaged sisters in our tribe, make them welcome and stand shoulder to shoulder with them in their struggles. And I say ‘their’, when at times of my life, this woman has been a version of myself, or people close to me. Feminism has long sought seats at the table for women in boardrooms and policymaking. Now disadvantaged women need to be heard.

References:

Culturemag.es (2021) “10 Songs about Female Empowerment”. Available at: https://www.culturemag.es/10-canciones-sobre-el-empoderamiento-femenino/. (Accessed: 11/11/22)

IPPR (2013) “Twentieth century feminism failed working class women”. Available at: https://www.ippr.org/news-and-media/press-releases/twentieth-century-feminism-failed-working-class-women. (Accessed: 04/11/22)

Pew Research Centre (2015) “Despite progress, women still bear heavier load than men in balancing work and family”. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/03/10/women-still-bear-heavier-load-than-men-balancing-work-family/. (Accessed: 04/11/22)

The New Stateman (2017) “Yule Pay”. Available at: https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/welfare/2017/12/everything-sun-didn-t-tell-you-when-shaming-mum-buying-christmas-presents. (Accessed: 11/11/22)

The Socialist Review (2018) “How austerity hurts women”. Available at: http://socialistreview.org.uk/443/how-austerity-hurts-women. (Accessed: 04/11/22)

UK Tabloids (2014) “Scroungers on £85,000 a Year Benefits”. Available at: https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/483925922432734567/. (Accessed: 11/11/2022)