This may seem a very strange question. Surely children can only know about language that which they hear, see or experience from the language users around them? After all, a child only learns the language(s) they are exposed to. No child in the UK, for example, grows up learning Auslan, unless they are exposed to it by an Auslan-signing parent.

But this question is a (less provocative!) rendering of one of the biggest open research questions in child language, and one which has split child language researchers, sometimes acrimoniously, since the mid 20th century.

You may be more familiar with this question framed as the “nature vs. nurture” debate, or the innateness debate. Both of these framings I find very weird. When you drill down, all child language researchers believe that both nature and nurture play roles in the acquisition of language by children. The real debates are around the nature of nature and the nature of the nurture. So let’s dive into exploring the two main approaches to these issues, starting with the group that proposes language-specific innate knowledge.

(Full disclosure first: I was trained and now work in the generativist tradition, I know it better, and I think it is more often misunderstood than the constructivist tradition, so I spend quite a bit more time on what follows describing the generativist point of view. Even so, I hope you find it interesting, and somewhat balanced in terms of critique.)

The Domain-Specific approach (a.k.a. the Generativists)

These are the scholars typically positioned as the “nativists”. They’re responsible for creating All the Acronyms (LAD, UG, PLD MMM*…) and are often accused of not taking the other side seriously, mostly because they don’t engage with their work very often (which is, of course, not good scholarship).

But generativists are very serious about their main claim: that human beings are born with some knowledge about language that they use to make sense of the bewilderingly complex language input they receive. This is known as domain-specific knowledge because, quite simply, it’s knowledge that pertains only to the domain of language, and no other cognitive domain. You may have also heard of it referred to as Universal Grammar – some language knowledge, even rules, that all children can use from birth.

Why make such a claim? Well, in part it is because it’s striking that children learning different languages actually pass through very similar developmental stages – adults do the same too when learning artificial languages, irrespective of their first language. This suggests that we don’t just have general learning biases or preferences, but that some biases exist that apply specifically to linguistic information.

The birth of a language: Nicaraguan Sign Language

One of the most compelling examples of this can be seen in the development of Nicaraguan Sign Language (NSL). NSL grew out of the opening of the first state-run school for deaf people in Nicaragua in the 1970s. Students came from all over the country and did not share a language, using instead a range of “home signs”. But as they interacted in the playground, conventions of use developed among the students – a lexicon with some rules. These rules, however, didn’t really resemble other languages. They did the job, and the children communicated and flourished. But a lot of the signs and structures relied heavily on representing events and things in the world fairly literally, and didn’t make use of many abstract markers in the way that full natural languages typically do (things like tense, aspect, person agreement, etc.).

When new, younger students arrived, they took this fledgling system and (entirely subconsciously) generated a true language grammar for it. The younger students used their innate compulsion to build a linguistic system, using highly arbitrary features like space and handshapes to create a complex system that could express more efficiently complex, abstract idea. This system – NSL – has a grammar that is fully recognisable as a natural language grammar. That’s to say that it is hierarchically structured, it doesn’t “count” (there isn’t a specific type of word that must be the third word in the sentence, for example) and its rules are regular in many of the same ways as any other language.

This brings us to another motivation for the generativist approach to understanding language acquisition: for all the logically possible ways in which languages *could* differ, they tend to structure their constituent parts along very similar lines.

What about the Poverty of…

Note that I haven’t mentioned (directly) a theory often cited as a motivation for a generativist approach: the Poverty of the Stimulus. It’s an idea that grew out of “Plato’s Problem” – the question of how humans extract so much information from limited evidence in their environment. With respect to language specifically, it is used to suggest that children simply don’t get enough linguistic evidence to be able to build a language grammar as quickly and as accurately as they do.

And for sure, it’s amazing that by the age of three, small children can engage in long narratives, ask questions, follow complex instructions and reason about the world, even though they can’t tie their shoelaces and some may still be in nappies. However, linguists who made (and make) this kind of argument are often only interested in syntactic strings, which don’t take into account all the *other* cues and pieces of information that actually accompany those strings when spoken or signed in context – intonation, gesture, context, growing world knowledge. Moreover, if we don’t have theories about children’s ability to reason, remember and recognise patterns across the information they receive, then the Poverty of the Stimulus is pretty vague. How much information is enough, and what information are children actually capable of using?

Speaking of vagueness, I will admit, as a card-carrying generativist, that claims about the content of possible domain-specific knowledge remain bafflingly vague. So let’s examine a couple of the more worked-out versions of Universal Grammar in more detail. Note that I’m skipping over quite a lot of historical detail here to focus in on just two approaches to understanding domain-specific knowledge – if you want to know more, come and do a degree with us in linguistics ;).

Rich UG: Principles and Parameters

In the past, some scholars assumed that Universal Grammar consisted of a very rich store of innate knowledge made up of universal linguistic principles and parameters – possible “settings” for those universals in different languages.

A famous example is the pro-drop parameter. Some languages allow users to “drop” the subject of the sentence (that is, not say it out loud). These languages include Italian, Spanish, American Sign Language, Mandarin Chinese, and many more – around two-thirds of the world’s languages, as far as we know. The exact rules that determine when you can drop a subject might differ, but the fact that you can drop a subject is what links them. Take examples (1-2) from Italian, and compare them with the English translations.

- (Io) sono felice.

“I am happy.” - Piove.

“It rains.”

In (1), the Italian first person pronominal subject “Io” is optional – “Sono felice” is itself a perfectly grammatical sentence in Italian. But in English, “I” is obligatory – “Am happy” would be considered ungrammatical most of the time. In sentences like (2), there is no subject in Italian, because weather verbs like piovere (‘to rain’) just don’t need subjects at all. But in English, we insert the expletive or pleonastic pronoun “it” to get “it rains”, because the grammar’s need for a subject is so strong that it doesn’t matter whether it actually refers to anything or not. It’s a purely grammatical requirement. Other languages that require the subject to be overt, like English, include French, Indonesian and Mupun, to name a few.**

How does this relate to acquisition? According to a theory that assumes principles and parameters, children will be (subconsciously!) listening out for how their language expresses subjects because they’ll ‘know’ it’s an important point of variation for grammar with a roughly binary set of values – either you can drop your subjects, or you can’t.

A theory like this is useful because it helps make predictions about what children might or might not be doing during language acquisition, which you can then test by looking at language corpora (sets of recordings of children) or by running experiments. Taking pro-drop as an example again, it is a common observation that English children drop subjects in their early speech, until around age 3. A theory like principles and parameters provokes an interesting research question – do English-acquiring children drop subjects because that’s grammatical for them to start with, because pro-drop is a default setting (a language-internal explanation), or for some other reason, like reduced processing ability (a language-external explanation)?

Linguists like Nina Hyams and Virginia Valian (among many others) have looked extensively at English children’s subject drop through this lens. They noticed that English-acquiring children’s subject drop is not like the subject drop of children learning Italian. Others also noticed that English children’s subject drop is not like the subject drop of children learning Mandarin (in which the rules on subject drop are a bit different from Italian ones). Mandarin also permits the dropping of objects, so Mandarin-acquiring children oblige, but English-acquiring children barely drop objects at all. Both Italian- and Mandarin-acquiring children learn adult-like pro-drop settings very early, while English-acquiring children are doing something quite different from both English-speaking adults and children learning pro-drop languages. English-acquiring children tend only to drop subjects when they’re the first thing in the sentence – that is, they don’t tend to drop subjects in more complex utterances like wh-questions or subordinate clauses, where other bits of linguistic structure precede the subject.

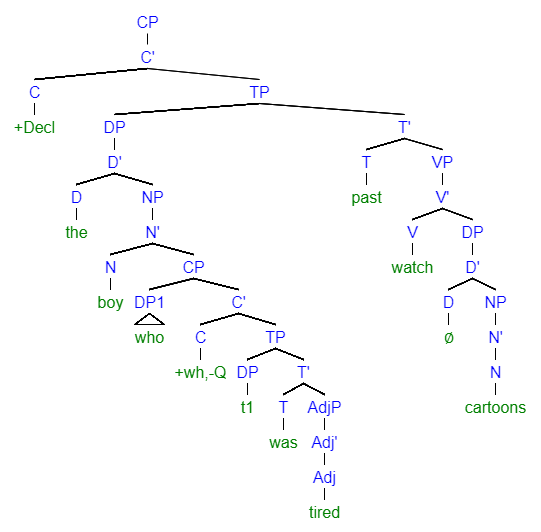

So what are English-acquiring children doing? They seem to be just missing out the very edge of their utterance, or in full linguistic parlance, the top-most part of the structure (given that sentences actually have hierarchical, not linear structures. More on that another time). Why might they do this? Linguist Luigi Rizzi made an influential proposal in the early 1990s, refined in the 2020s with colleagues Naama Friedmann and Adriana Belletti, that children learn sentence structure from the ‘bottom up’, with layers of information emerging in sequence, which may be “truncated” if their processing capacities become overwhelmed. According to Friedmann, Rizzi and Belletti’s “growing trees” hypothesis, children learn the structure of a sentence’s verb phrase (with any objects) first, then grow into marking tense and aspect, then into marking the subject, followed by things that mark how the sentence fits into a discourse, for example the wh-word in a question.*** The claim goes that at the point at which English-acquiring children are dropping subjects, they know that they are needed in English, but they’re still working out exactly what they look like and how they relate to the rest of the structure. All this work sometimes leads to truncation of the sentence – or in tree-surgeon parlance, the subject gets lopped off.

Though Principles and Parameters provided interesting ways to approach language acquisition (and language description more generally), it’s long been clear that it’s not a psychologically valid proposal for the domain-specific knowledge children might be born with – it is quite improbable that children’s innate tools for making sense of language would take such a highly specified form.

Parsimonious UG: Merge and Agree

A newer approach to domain-specific knowledge, deriving from an article by Noam Chomsky in 2005, proposes two processes (rather than a number of principles) that drive how children unpick their language input. Those processes are Merge and Agree.

Merge is, briefly, the process of taking two things (words, phrases, clauses…) and combining them to create a new linguistic object. Merge builds hierarchical structures, and we already have plenty of evidence that language is hierarchical, not linear. Grammatical rules reflect this, processing reflects this, and acquisition respects hierarchical structure.

Combining objects means that some relationship is formed between those objects – that they come to share or express some feature that we can use as language users to make meaning. So the language user needs to be able to recognise what features drive the combination of specific objects, as this will help them parse structure accurately (understand) and build new structures (produce language). The process of forming relationships between language objects is called Agree. To apply Agree, the language user also needs to form a set of features that are relevant in their language that can be recognised in the language objects, and which they could use again and again to parse any of the infinitely many sentences they might be exposed to in their input.

Let’s (try to!) get a bit less abstract now and return to the issue of pro-drop, with help from linguist Theresa Biberauer, who looked at pro-drop from the point of view of Merge and Agree in 2018. She argued that children acquiring their first language will be constantly looking for patterns across their language and looking for features – some abstract, some maybe less so – that link the structures in their input. As English-acquiring children very rarely hear sentences without subjects, and receive evidence for subjects that carry no independent meaning (expletive “it”), she argues that they won’t look for features that explain subject patterns because, quite simply, there’s no need to. There’s no ‘pattern’ to explain in that sense – you just need to have a subject, and English-acquiring children will pick this up early on, leaving their subject-dropping in production to be explained by other factors such as processing, or still needing to build the parts of the grammar that will connect up the subject with the main verb, such as auxiliary verbs.

The input to Italian- and Mandarin-acquiring children, however, leads them to pose a question – under what circumstances should I drop subjects? They then need to work out what features correlate with dropped subjects. For Mandarin, children will work out that what really matters are discourse features – subjects (and objects) can be dropped when they are topics that are somehow familiar in the conversation already. For Italian, children must realise that discourse matters – familiar subjects can be dropped – but grammatical agreement matters too. Subjects can be dropped because the verb is marked according to the person and number of the subject in Italian – in example (1) above, the verb form sono is the first person singular form of essere (‘to be’). But verbs aren’t marked for the person and number of the object, so objects can’t be dropped.

Noticing these features isn’t just useful for pro-drop, however! Being able to recognise topichood, subjecthood, person and number is also useful in both Mandarin and Italian for other aspects of grammar, like word order, and also for learning how intonation works. So having an innate compulsion to look for relationships between language objects really will speed acquisition along, because the features that characterise those relationships will pop up again and again in the broader language system.

Just because it ain’t language specific, doesn’t mean it ain’t innate…

You’ll note that, in the case of “parsimonious” UG particularly, there are implicit references to cognitive processes that aren’t domain-specific, like pattern-spotting, pattern-matching, awareness of frequency, and more. This is because generativists also make room in their theories for domain-general learning mechanisms – in other words, cognitive processes that aren’t specialised for language but that are used to learn language. We’ll talk more about these below, as they are the key tools in the theoretical arsenal of “the other side”, but they are crucial for the application of Merge and Agree, and are included in generativist theories as “third factors” – factors that aren’t domain-specific knowledge or the input itself.

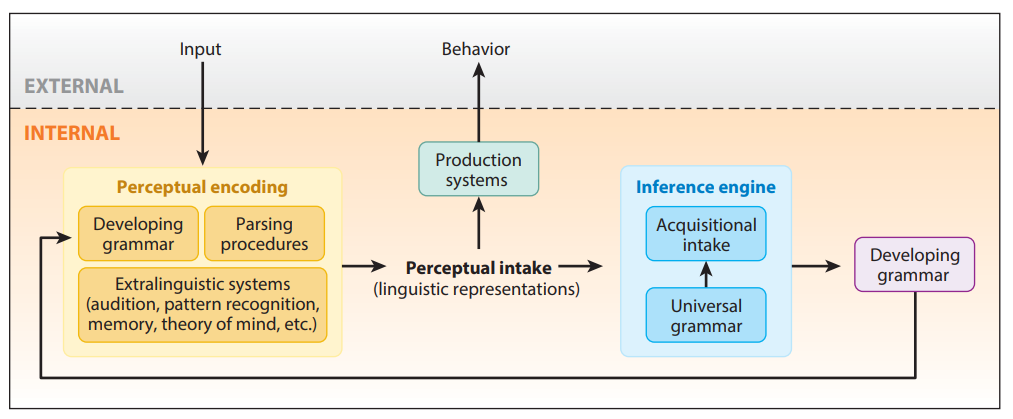

This label gives you a bit of a clue – these ‘factors’ aren’t the things that generativists are, generally, most interested in. But lack of interest doesn’t mean they’re ignored altogether. Indeed, some generativists take the interaction between general cognitive and language-specific processes very seriously. Linguists like Jeff Lidz and Annie Gagliardi build domain-general processes into their models of language acquisition in just the way described above – noting that general cognitive processes must apply to language input before language-specific processes, to provide filtered input that children could plausibly assess for where Merge applies, and what Agree processes are at work. They map their model in the diagram below, taken from their 2015 paper:

Theresa Biberauer also takes seriously the idea of “maximising minimal means”, that is, using and reusing features and observations you’ve already made. This is a domain-general process that would be useful for making sense of lots of different types of input. But with respect to language acquisition, she argues that it is a crucial third-factor used by children as they apply Merge and Agree to their input, and that it also drives some of the restrictions on variation that we see in natural language.

You’ve mentioned input a lot. I thought generativists weren’t too bothered about it…?

I think the most misunderstood aspect of the generativist approach to language acquisition is generativists’ stance on input. It is true that some generativists will take the “target” for acquisition to be the grammatical rules of the relevant language at a general, population level (i.e. what is generally considered to be grammatical in that language). Generativists are also often interested in comparing acquisition trajectories across languages so, again, they generalise across individuals and consider acquisition at a population level. This is in contrast to constructivists, who typically take into account only the kind of language that the individual child experiences – that is, the language used by their families and caregivers.

It’s pretty obvious how the two ‘targets’ here might differ, and how that would affect predictions that you would make. But input is always important, and generativists don’t assume or predict otherwise.

Given that we’re thinking about input, let’s turn now to our other set of players, for whom input drives not only acquisition, but much of their theorising and reasoning.

The Domain-General crew (a.k.a, amongst other things, usage-based researchers or Constructivists)

It’s a little harder to define a “main” claim of researchers for whom domain-general knowledge is the child’s only tool for making sense of their language input. That’s because there are a lot of different types of domain-general process to investigate – working memory, long-term memory, statistical generalisation, sensitivity to frequency, and so on. But something that is key for constructivists like Ben Ambridge and Elena Lieven, which differentiates them from generativists, is that children go from specific observations about their individual language input – e.g. storing particular phrases that they have heard/seen – to gradually generalising abstract rules. Memory, therefore, plays a major role in a constructivist account, whereas even the “third-factor”-interested generativists rarely, if ever, mention it.

What children can plausibly add to memory, of course, depends on what *exactly* they are exposed to. Sensitivity to frequency is a core theme in constructivist theories – children will appear more adult-like when they can use a stored phrase or string from memory, and less adult-like when the task they’re performing can’t be addressed using stored material. That frequency is important in language development is well established – it plays a role in language change in many levels of language, as well as language use, language processing, and patterns that emerge across languages (recall, this was an argument for domain-specific knowledge too…)

Given their focus on individualised input, constructivists also insist on the importance of understanding language acquisition as happening in interaction. As such, studies of the acquisition of pragmatics are dominated by constructivists, with Catherine Snow and Thea Cameron-Faulkner leading the charge****.

Right. So…null subjects from a usage-based POV?

Sorry lads. That’s what I wanted to write about here, but I cannot find an account of English-acquiring children’s null subjects from the constructivist side of things. I did find an account for Spanish, a pro-drop language like Italian. Hannah Forsythe and colleagues argued that the frequency in input of different types of pronoun affects when they begin to be dropped in adult-like ways – first and second person subjects are more frequent than third person subjects, and children achieve adult-like rates of dropped and overt subjects in first/second person cases first, before abstracting the same rules to third person subjects.

As for English null subjects, my guess, but this is only a guess, is that there are three routes to take to explain them using a constructivist lens.

One is to put all the blame on processing limitations of various types – which is of course, ultimately where we landed in the generativist approach too. Reading around a bit, and talking to colleagues of a constructivist persuasion, this seems like a bit of a cop out.

My excellent colleague Dr Nick Riches suggested a second take: subjects don’t add much grammatical information to an utterance – especially when first and second person subjects are so much more common in child speech than third person ones. This is in contrast with objects, which are important for indicating the argument structure of verbs (and, of course, the less obvious identity of the object). So if children are going to drop any information (because of gradual acquisition, or processing pressures), the subject is the least informationally dense element.

The third route is to assume (as constructivists do) that the child’s grammar is very different from an adults, and then go looking at the rate of utterances that have no subjects in the input *regardless* of the morphological form of the verb. Key here are imperative verbs – these are very frequent in child input and *don’t* require a subject but, in English, are not overtly marked as imperative. They look superficially exactly the same as most verbs in the present tense, and infinitives too. I guess a constructivist could argue that imperative verbs could provide sufficient evidence for certain verbs not needing a subject, at least in very early child language. To argue this you’d have to have a story about how children ignore the specific pragmatic use of imperatives, but maybe that’s doable.

It’s also important to note that usage-based approaches tend to focus, perfectly legitimately, on children’s production in terms of evidence for their grammar. This is of interest to generativists, of course, but generativists are also interested in children’s comprehension. So while both approaches will look at production in their accounts, generativists are also likely to probe children’s grammar by looking experimentally at how they react to grammatical and ungrammatical sentences.*****

What all this illustrates, though, is how the “two sides” here are not two sides of the same coin. At best, we’re looking at the head of a pound coin and the tails of a 50p. The two approaches work within the same field, but often look to answer quite different questions – and they’ll make use of different data to support their own arguments. As it turns out, those data don’t necessarily overlap all that much, *even* in a language as heavily studied as English.

I’m doing my A-levels. How can I make sense of all of this for the exam?

I have a few ideas here, but this is a topic I’m probably going to return to in more depth in a future blog post too. Also, bear in mind that I’m pretty well acquainted with the specifications for some of the large exam boards (particularly AQA and OCR), but I’m still not as steeped in them as trained teachers are! But if you’re interested to know my initial thoughts, then please continue…

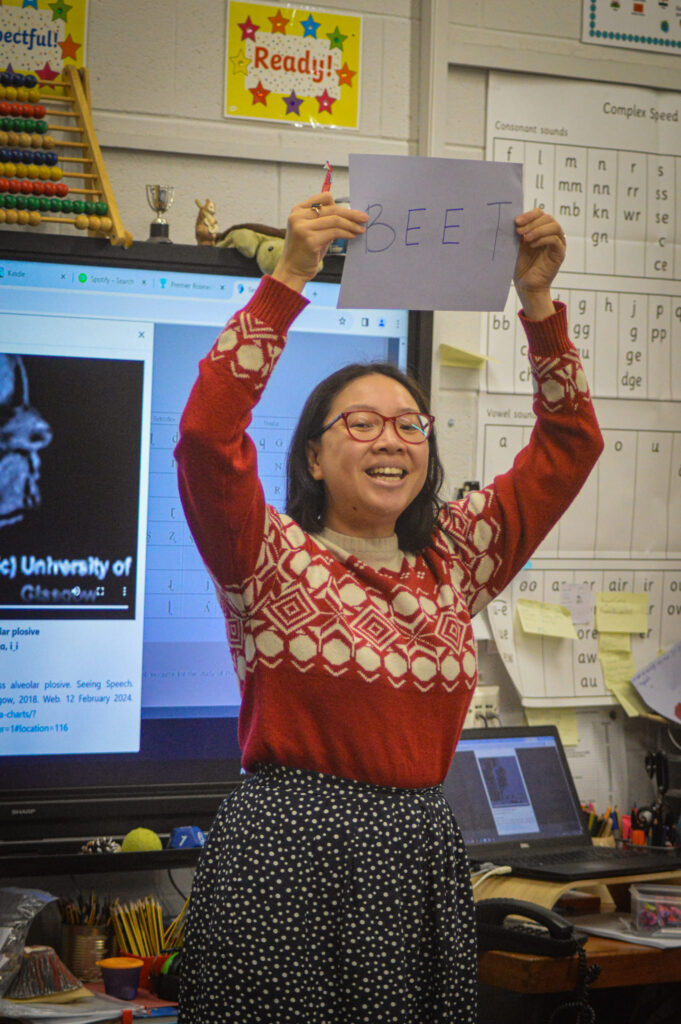

Key to the exam first and foremost (and to linguistics in general) is the ability to accurately *describe* children’s production, so above all else, ensure that you are confident in labelling parts of speech and morphemes and that you can spot and describe features like person and number, both for the adult target and the child’s production. Also, don’t focus just on children’s non-adult-like production – give them ‘credit’ for what they *can* do in an adult-like way too, whether that’s producing subjects, using relevant auxiliary verbs, and so on.

Given the direct link that constructivists make between the child’s individualised input and their production, it’s a little easier to see how you could zoom out from transcripts of child language to talk about constructivist approaches to language acquisition. Even then, the role of frequency is hard to address from fragments of transcripts, so to be true to constructivist techniques, you’d have to talk about what you would look for if you had more examples of dialogue from the same child-caregiver pair.

With respect to linking from transcripts to generativist claims, the “growing trees” hypothesis is interesting to link to in terms of evaluating why verb phrase syntax is adult-like earlier than tense and subjects. You can also think about what grammatical features a child needs to work out for different linguistic items that are in the transcript and what interim features they might propose – features are a good way of thinking about and comparing linguistic complexity. As an example, determiners like “the” and “a” differ in terms of definiteness, but “a” is even more complex because it can be used both with specific and non-specific nouns, and is also specified for number (singular only). So there are three features that a child has to learn when trying to pick a determiner, and the determiner options differ in their featural complexity. Imagine what effect that could have on the acquisition of determiners in English.

Notes

*Language Acquisition Device (see ******), Universal Grammar (described in text), Primary Linguistic Data (=input!), Maximising Minimal Means (described in text)…and many more!

**If you’d like to know more about how languages express subjects, take a look at the World Atlas of Language Structures. You can also find lots more information about the structures of hundreds of languages all over the world on this fantastic website.

***There’s a competing hypothesis under development by Martina Wiltschko and my very good colleague Johannes Heim, called the “Inward Growing Spine Hypothesis“, which suggests that structure grows inward from the bottom (the verb phrase) and the very top (discourse-related phrases that call on the addressee to respond, like vocatives). I’m not sure either approach is *quite* right, but Wiltschko and Heim’s idea that some of the very topmost structure does come in early is clear from early child utterances. The question is – which parts of the topmost structure? I’m working on my own contribution to this question – watch this space 😉

****Generativists, it should be noted, have spilled a lot of digital ink on one particular aspect of pragmatic acquisition, namely the topic of scalar implicatures. But that’s a topic for another day.

*****Obviously, you can’t just ask a small child whether they find an utterance grammatical or not – in fact you can’t do this until they’re about 6 or 7 years old (and even then, we’d use more child-friendly wording!). But you can interpret children’s behaviour in response to stimuli in lots of clever ways to probe what they do and don’t know about the adult grammar.

******LAD – Language Acquisition Device. A term from Noam Chomsky’s early work to represent an (unspecified) process or set of processes and knowledge that the child is born with and that specifically concern and work over language input. Not in use by generative linguists today.

And a postscript…

I may have become a bit delirious when initially planning this post (I was at a soft play centre too early on a Sunday morning. It does strange things to you) and I ended up casting the two competing approaches as the Capulets and Montagues in a terrible rewriting of the prologue from Romeo and Juliet. Trigger warning: what follows might constitute cultural vandalism…

Two (main) factions, both alike in indignancy

In Academia, where we set our scene

From old grudges break to new strawmen

Where wilful snubs make wilful claims quite mean.

From forth the messy output of these groups

This messy cross-referenced blog takes shape;

Whose well-intentioned overview does aim

To make clear where their paths each other trace.

Generativists from LAD****** through UG

Move, while constructivist claims also persist.

I cannot claim to end the feud – not me! –

Just reveal of what the arguments consist.

The which, if you with patient thumbs scroll through

What here I’ve missed, I toil now to construe.