It’s 7.30pm on a July evening. I’m lying in the dark, small shafts of light filtering into the room between the blackout blinds and the curtains. I can’t move and I’m trying not to breathe too loudly.

I’m trying to get child #2 (we’ll call him Squidge) to sleep. Squidge, not quite 2-and-a-half, is lying next to me and having none of it. He just wants to try out his new linguistic skills.

His eyes are still open and my arm is going numb, so I decide there’s no harm in getting more comfortable. As I shift in his narrow bed, a strand of my hair falls across Squidge’s face.

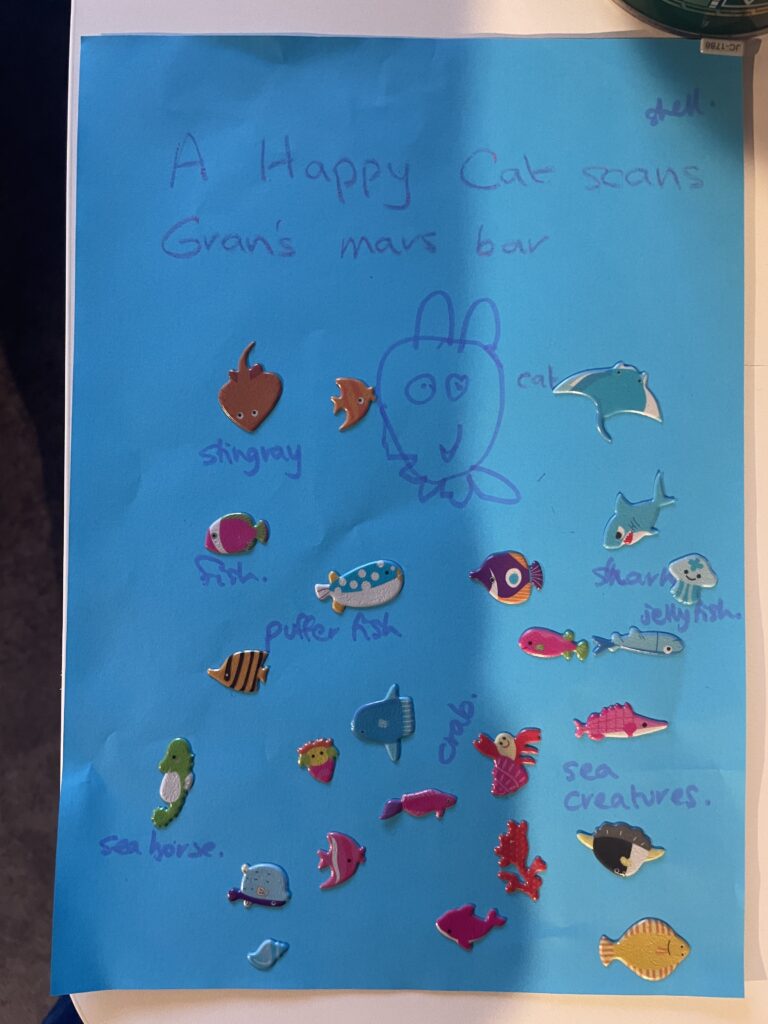

“Put my hair on your nose,” he says.

“Put your hair on your nose.

Put your hair on my nose.”

I make an immediate mental note of this pronominal poetry for later.

The same week I receive an email from a colleague who listened to my Free Thinking episode on Childhood and Play, asking the following:

I’m particularly interested in the move from third-person to first-person speech in early childhood: primarily (it seems, as a non-expert) structured and modelled by the parent. There’s a move from “where’s Peter’s nose?” and “it’s mummy’s turn…now it’s Peter’s turn”, to “my” and “your” with the timing of the move possibly(?) led by the child.

Do you know if there’s been much research into this phenomenon and what it reflects and depends on?

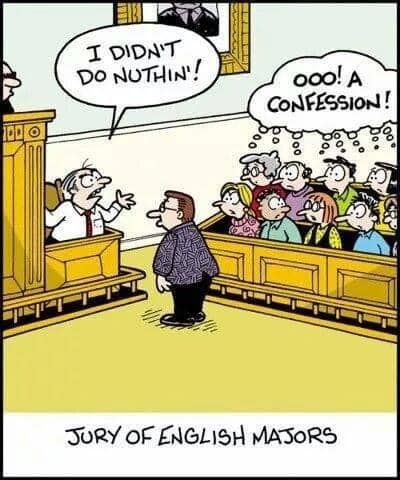

There are two slightly different questions here, which meet each other in their interest in how children learn pronouns, which are indexical parts of speech; that is, items in language that shift their meaning depending on context.

You and me always…

Let’s take Squidge’s linguistic musings first, because there’s quite a bit more work been done on this than on the second question. Let’s describe what Squidge does first.

In commenting on the scene, Squidge intended to say “You put your hair on my nose.” Abstracting away from the dropping of the first “you” (a common process in early speech), he ‘reverses’ the second-person possessive pronoun “your”, using first-person possessive “my” instead, in reference to the noun “hair”. He then repeats the trick in the opposite direction with reference to the noun “nose”. This is not an isolated incident either – though this moment stood out because of the way in which he noticed his own “error”*, I was quite used by now to him referring to himself using second-person pronouns.

It’s unclear how common reversal of pronouns is in child language. It’s typically associated with children who are autistic, blind, or hard-of-hearing, though very early talkers also seem to reverse pronouns with some frequency, and eldest children seem more prone to do so too.

Squidge doesn’t fall into any of these categories (as far as we know), but there are also plenty of case-studies of typically developing children reversing pronouns, especially swapping out first- for second-person pronouns (the “nose” case), around two years of age. One other way in which he does align with other children in the literature, including some children with autism, is that he is quite an imitative child – impressionistically, he’s a much more enthusiastic (usually immediate) repeater of what he hears than, say, his older brother. So what’s going on?

I am me, so are you…

In general, pronouns present a fascinating example of the difference between children’s production of language (their performance) and their comprehension of it (their competence). While most children use first person pronouns very accurately early on, followed by second and third person pronouns (e.g. he, she, they), they tend to interpret second person pronouns more accurately to start with, followed by first and third person pronouns. In short, they appear to be using first-person pronouns before they’ve fully grasped the full meaning and use-conditions of them.

It’s easy to see why it could be tricky to interpret the difference between “you” and “me/I”, precisely because they shift their referent with each new speaker. Well, sort of. Though the only person who will use “I” to refer to me is me,** I am “you” to a whole range of people. So, plausibly, “you” is just another name for me – at least, this is a hypothesis that a child could make.

That said, that doesn’t seem to be what Squidge is doing, because he’s reversing possessive pronouns (i.e. your and my) as well. Another theory is that some children might understand that there’s a perspective shift involved in pronouns, but not when and how that works. This is also a plausible attempt to make sense of pronouns, given how other parts of language like go and come are more or less acceptable based on perspective.

Whatever a child’s initial hypothesis about you and me, they’ll be “you” to others throughout their life. So what makes a child, especially one who has been prone to pronoun reversal, shift like an adult?

When two become three

The early talker studies suggest a couple of triggers that might lead children out of the pronoun jungle. One is based on the observation that many of the reported pronoun-reversers in the literature are eldest children, who won’t necessarily have been exposed to many “triadic discourses” – that is, conversations involving three (or more) people.

Triadic conversations not only have multiple Is, they will also involve at least two yous that aren’t your own self. It might be a coincidence to share a name with one other person in the room, but add another and it starts to look like something else is going on (unless, like me, that name is Rebecca and you were born in the late 1980s. Then, you’re never alone).

Given that triadic conversations become more of a common experience for children when they experience childcare outside the home, or a family holiday, these things could constitute an external trigger that would make a child rethink how they interpret you. Indeed, Yuriko Oshima-Takane and her colleagues showed that second-born children, who are often in triadic situations from birth, are generally more adult-like in their pronoun use from an earlier age than firstborn children.

Pronouns? They’re child’s play!

Another trigger proposed by Evans and Demuth is a cognitive one. They noticed that a number of the neurotypical pronoun-reversers in the literature stopped reversing pronouns around 2;4 (that’s 2 years 4 months of age). In the case of the child they studied, the shift was very abrupt – she went from reversing nearly 100% of her first-person pronouns to none at all between recording sessions (that’s to say, within about a week).

As a result, they suggest that some internal process of cognitive maturation taking place at around age 2;4 might contribute to the child’s ability to use different linguistic terms to refer to different participants in a conversation. Naomi B. Schiff-Myers, in her observation of her own young pronoun-reverser, Lauren, noticed that Lauren stopped reversing pronouns around the same time that she started to role-play with dolls and invite more imaginative play.

Indeed, two months on from that long evening with Squidge, I can report that he doesn’t pronoun-reverse any more. It’s hard to say exactly when he stopped, but we have also noticed a huge uptick in playing imaginative games, where he takes on a range of roles and interacts more with other ‘players’ than he might have done previously. He seems, at least, to be one more anecdotal brick to add to the ‘cognitive maturation’ wall.

Naming the issue

And so to the second question about self-reference, or more precisely, referring to yourself by your own name. When children do this, effectively referring to themselves in the third-person, how do they switch to more adult-like first person pronouns?

Let’s give an example first. A friend of mine came round for a cup of tea and I witnessed the following exchange between her and her two-year-old daughter Jane (all names are changed):

Friend: Mummy’s drinking her water. Can Jane drink her water?

[hands Jane her water bottle]

Child: Jane’s bottle.

My friend was very consistent in referring to herself as Mummy and her child as Jane at first mention in an utterance, and using third person pronouns thereafter. Jane was similarly consistent in using full names and didn’t produce a single personal pronoun during that visit (though now aged three, she uses them as accurately as any other child).

Interestingly, it seems that the consistent full-namers, like Jane, may be a completely different group of children than the pronoun-reversers like Squidge. Schiff-Myers (mum of pronoun-reverser Lauren) notes, based on another study by Rosalind Charney, that children use their own names to avoid pronoun confusion (a claim corroborated in another, later study), but that this is not a route available to Lauren as she does not refer to herself using her own name (though she demonstrably knows it). I should note here that neither Squidge nor we as caregivers frequently use full names for self-reference either.

Schiff-Myers even goes on to suggest that using a child’s name instead of pronouns might be of clinical use for children who have delayed language, though this ignores the fact that using a personal name in place of pronouns consistently is marked in typical adult speech and might not come naturally to some caregivers.

How common is it for caregivers to use personal names in place of pronouns? It has been reported that personal names are used much more frequently in child-directed speech than in adult-directed speech – Adi-Bensaid and colleagues report this for caregiver and child names in Hebrew child-directed speech. It is likely that at least some of this uptick in personal name use is in place of pronouns, though other studies find that personal names lag behind far pronouns when used as subjects and objects of sentences in child-directed speech.

Essentially, not much work has been done on how caregivers refer to themselves and to their children, and whether idiosyncratic differences in self-naming affect how children acquire pronouns. We also don’t know much about how full-namer children transition out of full-naming themselves, as this route to pronoun acquisition hasn’t really been studied.

That said, I would expect the triggers that nudge pronoun-reversers towards adult-like pronoun use to have a similar effect on full-namers. As full-namers experience triadic conversations with new conversational partners, they will likely be exposed to people who don’t use personal names in place of pronouns. They will therefore, like the pronoun-reversers, gain more evidence that “you” shifts with the addressee and “I” with the speaker.

The effect of a step in cognitive development is harder to hypothesise about, as we might expect full-namers to continue role-playing with full names. But perhaps, again, role-play with other players would likely lead them to be exposed to different ways of speaking than the child-directed speech they’re used to.

At least now I know what to propose to this year’s students by way of dissertation topics!

Notes

*I don’t really like to refer to children’s non-target-like utterances as “errors”, because according to their grammar at the time, it might not be an error at all. However, “error” is a lot shorter, quicker to read and more transparent than “non-target-like utterance”, so I will scare-quote it instead.

** Forgive me this tortuous locution – I was trying to avoid saying “Only I can call myself “I”. While on one reading (the referential reading), this much shorter statement is true, it’s also untrue on another reading, the bound variable reading, which garnered much attention in formal linguistics following an influential article by the legendary Angelika Kratzer in 2009. They say formal linguists are nerdy…they’re not wrong.

References

Charney, Rosalind. 1980. Speech roles and the development of personal pronouns. Journal of Child Language 7, 509-528. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000900002816

Dale, Philip & Catherine Crain-Thoreson. 1993. Pronoun reversals: Who, when, and why? Journal of Child Language, 20(3), 573-589. doi:10.1017/S0305000900008485

Evans, Karen E. and Katherine Demuth. 2012. Individual differences in pronoun reversal: evidence from two longitudinal case studies. Journal of Child Language 39(1), 162-191. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000911000043

Kratzer, Angelika. 2009. Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 40(2), 187–237. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2009.40.2.187

Laakso, Aarre, & Linda B. Smith. 2007. Pronouns and verbs in adult speech to children: A corpus analysis. Journal of Child Language, 34(4), 725-763. doi:10.1017/S0305000907008136

Oshima-Takane, Yuriko, Elizabeth Goodz and Jeffrey L. Derevensky. 1996. Birth order effects on early language development: do secondborn children learn from overheard speech? Child Development 67(2), 621-634. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1131836

Schiff-Myers, Naomi. B. 1983. From pronoun reversals to correct pronoun usage: A case study of a normally developing child. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders 48, 385–94. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1044/jshd.4804.394