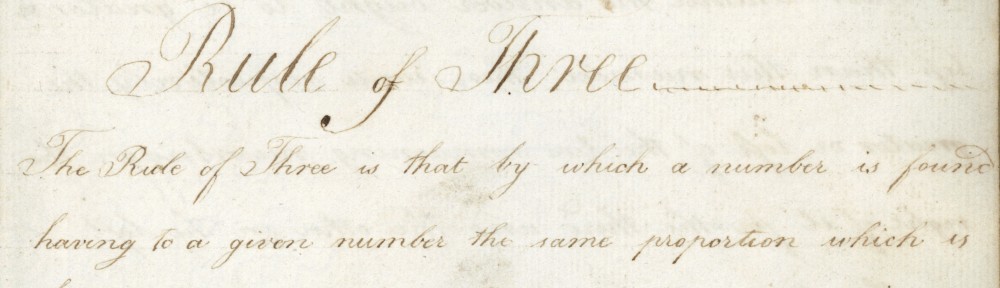

Prologue from ‘Round about the coal-fire: or Christmas entertainments’ (19th Century Collection, 19th C. Coll 398.268 CHR)To get you in the Christmas spirit, here’s the Prologue from ‘Round about our coal fire, or, Christmas Entertainments’ “wherein is described abundance of Fiddle-Faddle-Stuff, Raw-heads, bloody-bones, Buggybows and such like Horrible Bodies; Eating, Drinking, Kissing & other Diversions…” produced in 1734.

Author Archives: nspeccoll

The Fig Tree #ChristmasCountdown Door no. 17

‘The Fig Tree’ illustration from Elizabeth Blackwell’s Herbal Vol. 1

Plate 125. The Fig Tree. Ficus.

It seldome grows to be a Tree of any great Bigness in England; the Leaves are a grass Green and the Fruit when ripe of a brownish Green; it beareth no visible Flowers, which makes it believed they are hid in the Fruit.

Its Native soils are Turky, Spain and Portugal; and its time of Bearing is in Spring and Autumn; the Figs are cured by dipping them in scalding hot Lye, made of ye Ashes of the Guttings of the Tree, and afterwards they dry them carefully in the Sun.

Figs are esteem’d cooling and moistning, good for coughs, shortness of Breath, and all Diseases of the Breast; as also the Stone and Gravel, – and the small Pox and Measels, which they drive out. – Outwardly they are dissolving and ripening, good for Imposthumations and Swellings; and pestilential buboes.

Latin, Ficus. Spanish, Igos. Italian, Fichi: French, Figues. German, Fengen. Dutch Uygen.

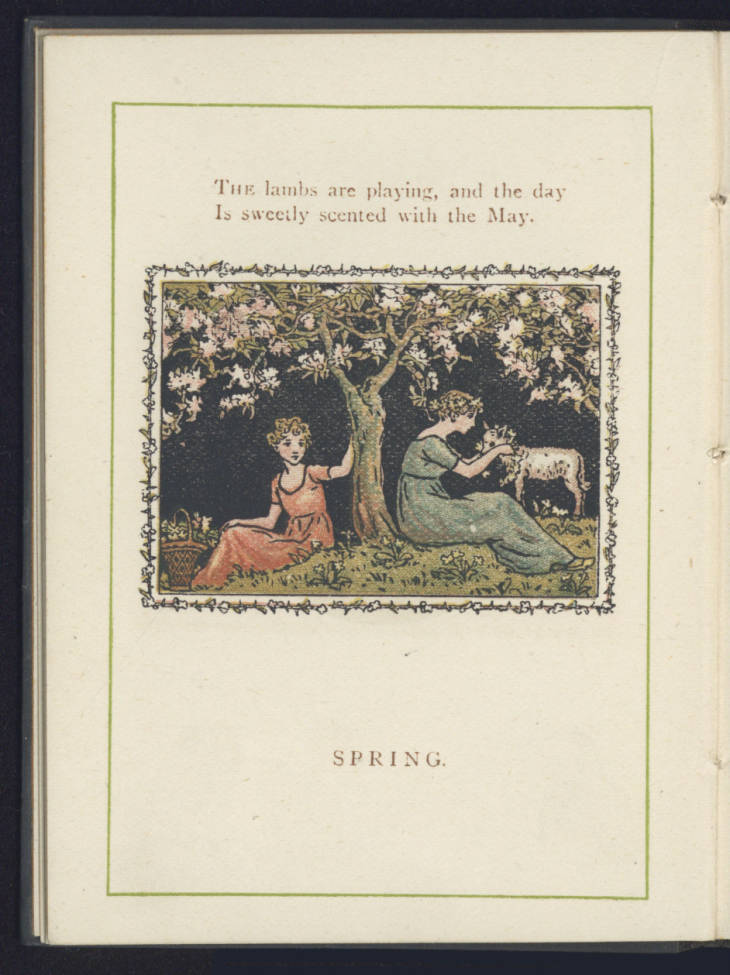

The seasons from 1890 Kate Greenaway’s Almanack – #ChristmasCountdown Door no. 16

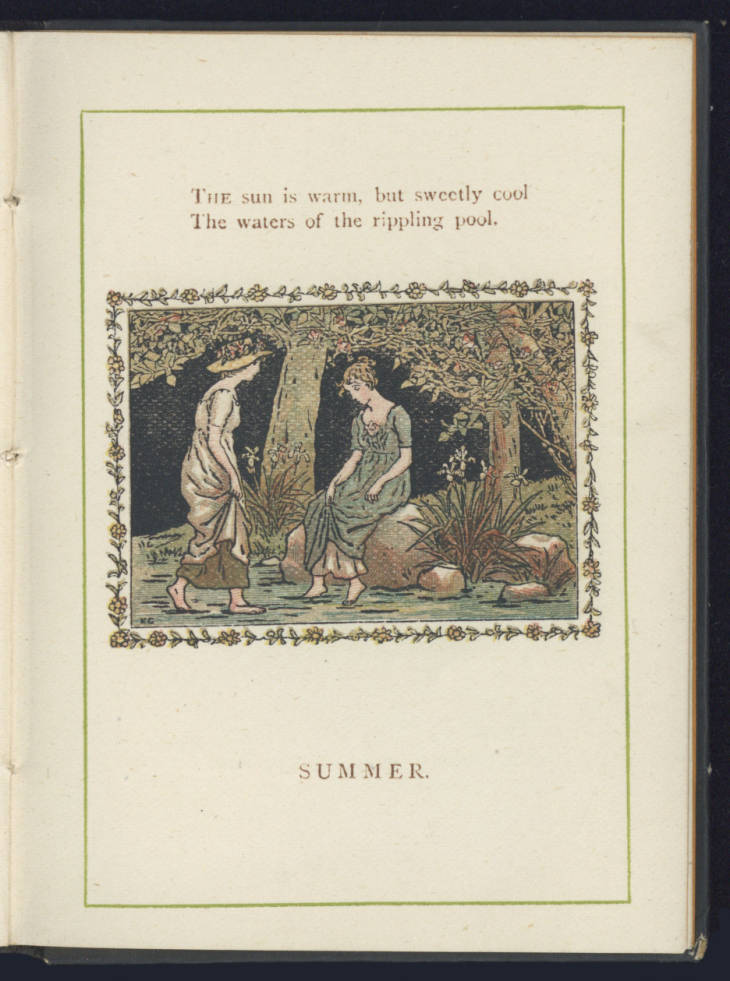

Page from Kate Greenaway’s almanack 1890 (19th Century Collections, 19th C. Coll 030 GRE)

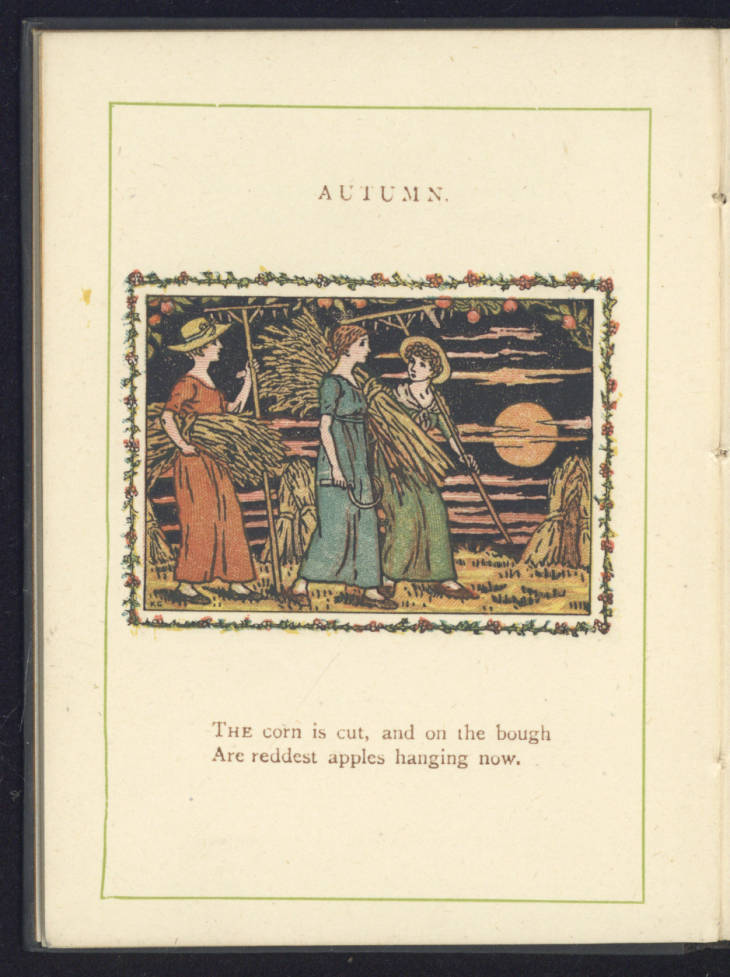

Page from Kate Greenaway’s almanack 1890 (19th Century Collections, 19th C. Coll 030 GRE)

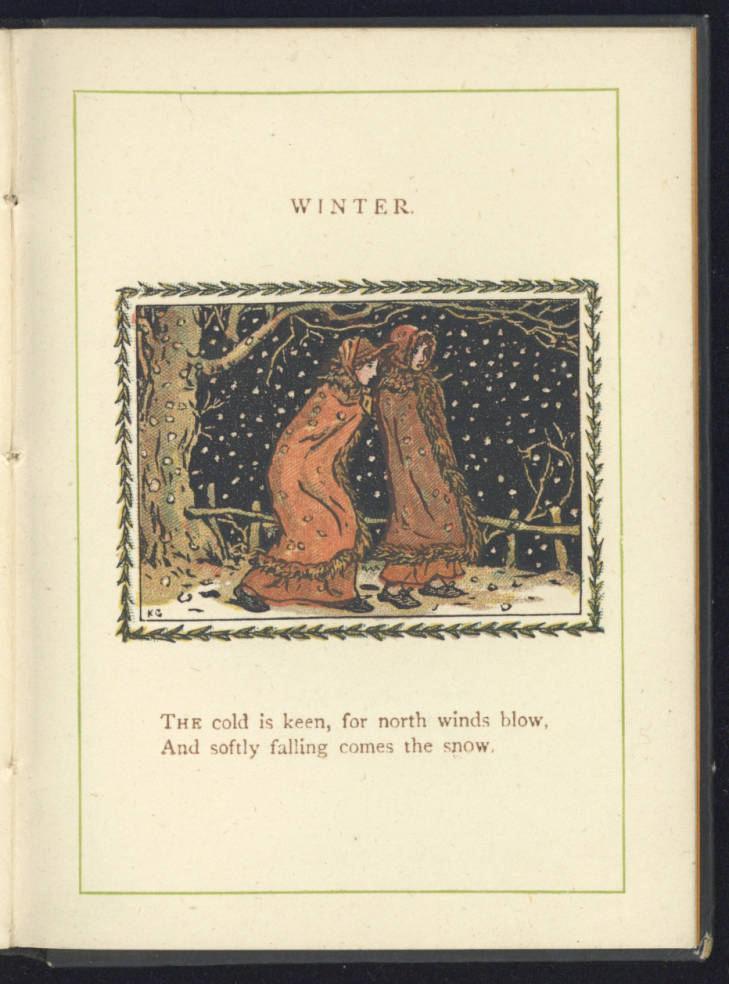

Page from Kate Greenaway’s almanack 1890 (19th Century Collections, 19th C. Coll 030 GRE)

Page from Kate Greenaway’s almanack 1890 (19th Century Collections, 19th C. Coll 030 GRE)

The below extract is taken from Kate Greenaway’s 1890 almanack and describes the seasons through rhyme and accompanying illustrations…

“SPRING

The lambs are playing, and the day

Is sweetly scented with the May.

Summer

The sun is warm, but sweetly cool

The waters of the rippling pool.

AUTUMN

The corn is cut, and on the bough

Are reddest apples hanging now.

WINTER

The cold is keen, for north winds blow,

And softly falling comes the snow.”

Catherine Greenaway (1846 – 1901), known as Kate Greenaway, was an English children’s book illustrator and writer. Her almanacs ran from 1883 up until 1897, with no 1896 issue being published. Each almanacks included a Jan-Dec calendar, beautifully drawn illustrations and short poems. Her almanacs were sold throughout America, England, Germany and France and were produced with different variations and in different languages.

Spiral Nebula in the Snow – #ChristmasCountdown Door no. 15

Photograph of Herschel Building and ‘Spiral Nebula’ sculpture, 1963 (University Archives, NUA/026961-4)

Here’s a snowy and wintery image from our University Archives.

Photograph of Geoffrey Clarke’s sculpture, in the snow, in front of Sir Basil Spence’s Herschel Building at Newcastle University, for the Department of Physics, taken 1963.

‘Spiral Nebula’ (also known as ‘Swirling Nebula’) was designed by noted post-war sculptor Geoffrey Clarke in 1962. It is a leading example of post-war public art. It is one of the few from this period that is situated in Newcastle.

It was commissioned by the architect Basil Spence as part of the design of the Herschel Building for the Physics Department of Kings College, University of Durham (which later in 1963 became Newcastle University). It reflects the scientific advances being made at this time, such as Britain’s first satellite, ‘Ariel 1’, which was launched in 1963 (the same year as the building was opened and sculpture unveiled).

Read more about the sculpture’s history and its revival here.

‘Spiral Nebula’ was one of five pieces of post-war public art in the North East to be given listed status at Grade II by Historic England in August 2016 (announced by Historic England September 2016). Read more here.

This photograph is part of the photographic section of the University Archives. To see more images of ‘Spiral Nebula’ in situ and being constructed, visit CollectionsCaptured.

Public Reading of a Christmas Carol #ChristmasCountdown Door no. 14

Although he is famed as a novelist and journalist, it is a fact perhaps less well-known that, during the last twelve years of his life, Charles Dickens (1812-1870) embarked on a new career for himself as a highly successful performer, touring Britain and America to deliver public readings from his novels and stories to thousands of people.

From 1853, Dickens had given successful public performances of his work for the benefit of charities, but from the late 1850s a feeling of restlessness combined with an inclination to accept invitations to read for money – perhaps owing to his recent purchase of a house, Gad’s Hill Place in Kent – and he began to give professional commercial public readings.

Dickens gave his first commercial reading in London on the evening of 29th April, 1858. Travelling with a manager, a valet and a technician, he used a simple stage-set of a small reading desk with a screen behind it to act as a sound-board for the projection of his voice, illuminated by gas-fittings hanging from a lighting rig above the stage. He rehearsed carefully and intensively so that he knew his texts by heart, and would improvise spontaneous variations in response to the reaction of a particular audience. As he read aloud he assumed the various roles and characters from his stories, imitating their accents and mannerisms to create a dramatic performance which was more than simply reading aloud from a book, and which delighted the crowds.

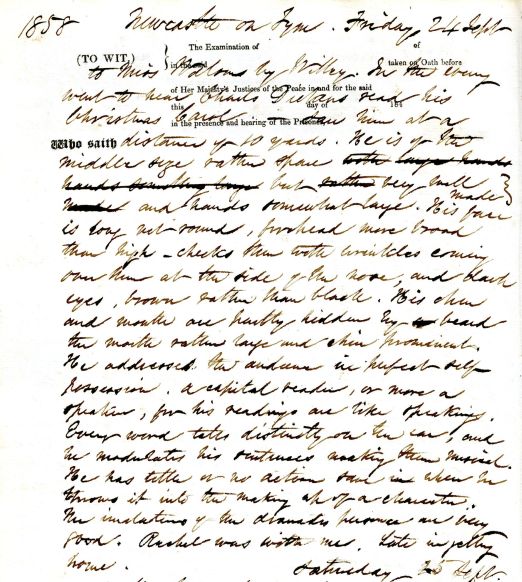

After his success in London Dickens went on to tour a number of provincial English cities, including Newcastle upon Tyne, and present in the audience there on 24th September 1858 for a reading of A Christmas Carol was the antiquarian Robert White. The White (Robert) Collection was presented to the then King’s College Library (now Newcastle University Library) by his family in 1942, and are now held in Special Collections. Contained in a journal amongst his papers is this vivid eye-witness account of his trip to hear Dickens read on that occasion.

White begins, “In the evening went to hear Charles Dickens read his Christmas Carol – saw him at a distance of 10 yards.” He goes on to give a detailed physical description of Dickens, including his forehead which is “more broad than high”, “cheeks thin with wrinkles coming over them at the side of the nose, black eyes, brown rather than black… His chin and mouth are partly hidden by a beard – the mouth rather large and chin prominent.”

Of the performance itself, White writes enthusiastically, “He addressed the audience in perfect self-possession, a capital reader, or more a speaker, for his readings are like speakings. Every word falls distinctly on the ear… He has little or no action save when he throws it into the making up of a character. His imitations of the dramatis personae are very good.”

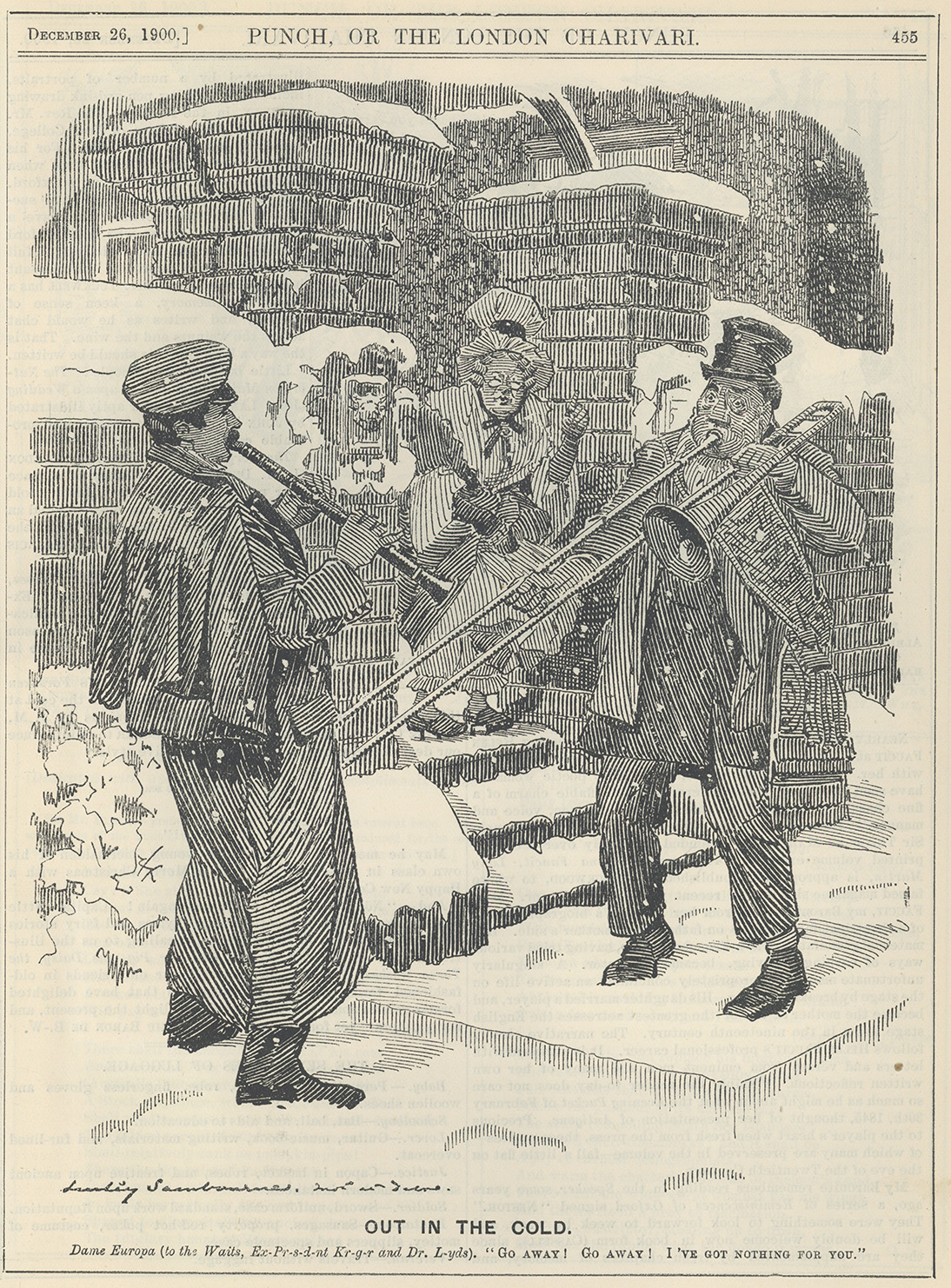

‘Out in the Cold’ from PUNCH #ChristmasCountdown Door no. 13

“Go Away! Go Away! I’ve got nothing for you.”Image from Punch Volume 119 (1900) – ‘Punch, or the London Charivari’, December 26th 1900

PUNCH, also named The London Charivari was a British weekly magazine of humour and satire established in 1841 by Henry Mayhew and engraver Ebenezer Landells. Historically, it was most influential in the 1840s and 1850s, when it helped to coin the term “cartoon” in its modern sense as a humorous illustration. After the 1940s, when its circulation peaked, it went into a long decline, closing in 1992. It was revived in 1996, but closed again in 2002.

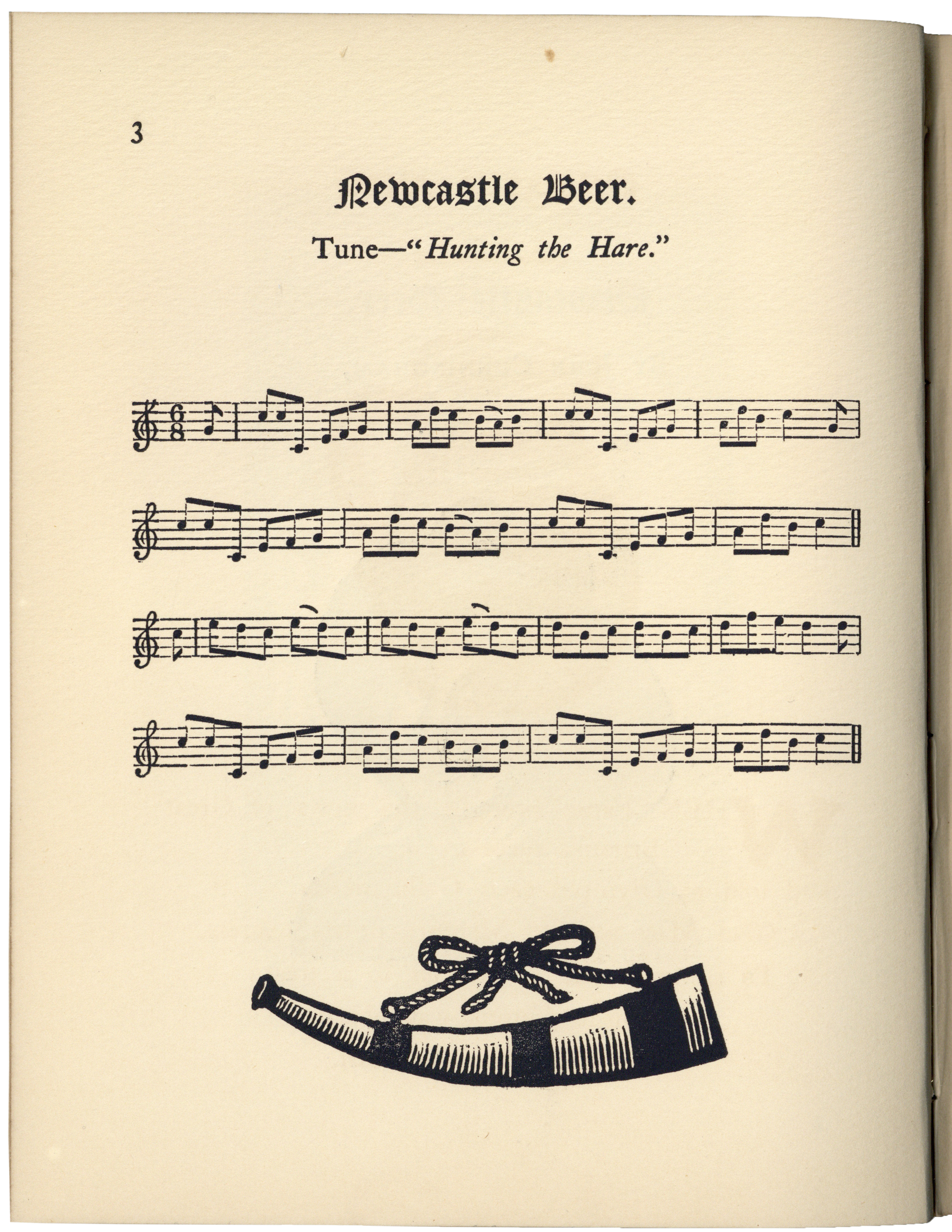

Newcastle Beer – #ChristmasCountdown Door no. 12

‘Newcastle Beer’ from A Beauk o’ Newcassel Sangs (Joseph Crawhall II Collection, Crawhall 12)

“When fame brought the news of Great Britain’s success,

And told at Olympus each Gallic defeat,

Glad Mars sent to Mercury orders express,

To summon the Deities was plac’d

To guide the gay feast,

And freely declar’d there was choice of good cheer;

Yet vow’d to his thinking,

For exquisite drinking,

Their Nectar was nothing to Newcastle Beer.”

Joseph Crawhall II was born in Newcastle in 1821 and was the son of Joseph Crawhall I, who was a sheriff of Newcastle. As well as running the family ropery business with his brothers, he also spent his time illustrating, making woodcuts and producing books.

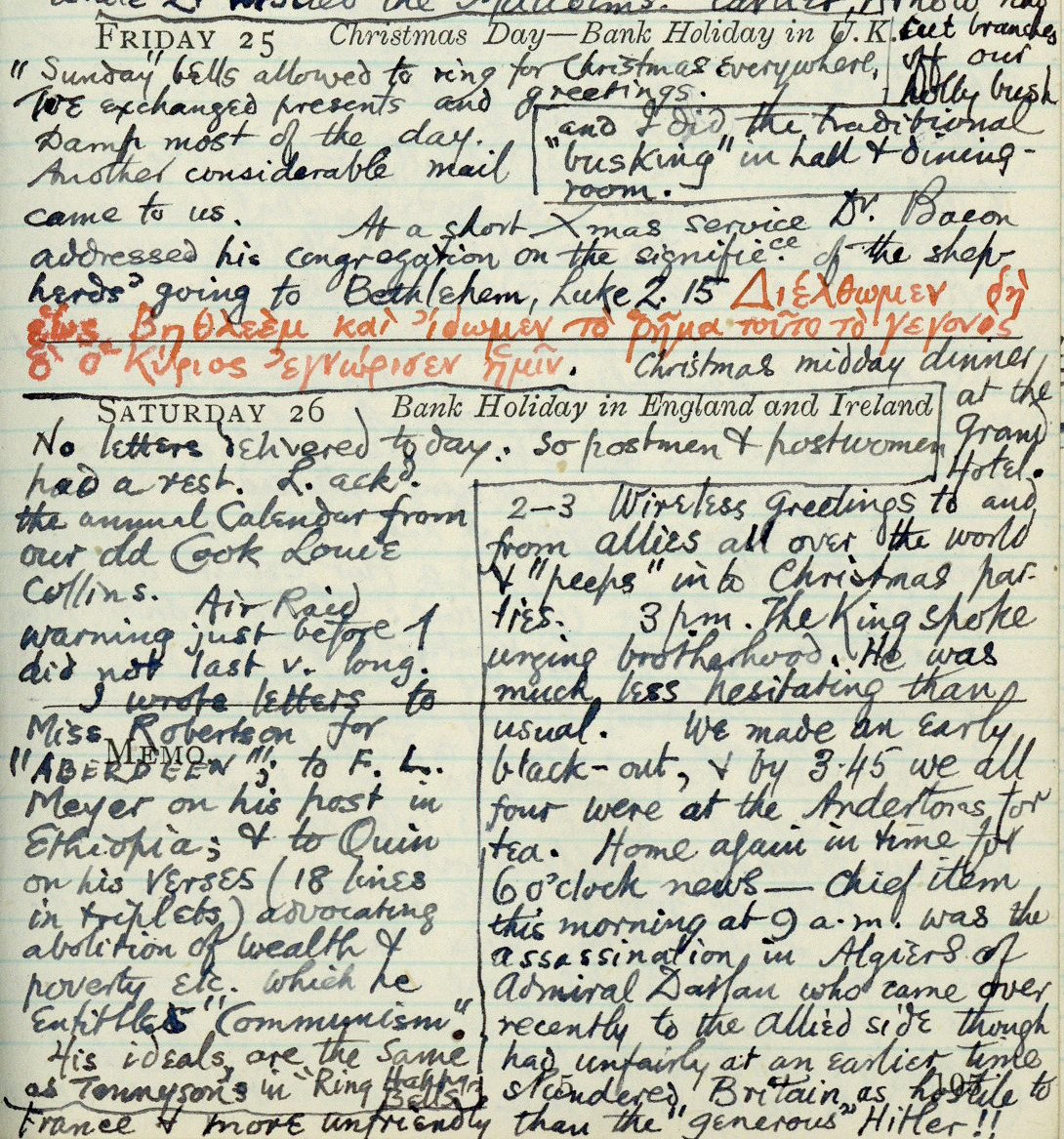

Professor Duff’s 25th December 1942 Diary Entry #ChristmasCountdown Door no.11

25th December 1942 diary extract from Professor Duff

Extract from Professor Duff’s 1942 diary entry. Professor Duff explains what he did on Christmas day and of the assassination of admiral Darlan during World War II.

FRIDAY 25 Christmas Day – Bank Holiday in U.K.

“Sunday” bells allowed to ring for Christmas everywhere. We exchanged presents and greetings. Damp most of the day. Another considerable mail came to us. At a short Xmas service Dr. Bacon addressed his congregation on the significance of the shepherds going to Bethlehem, Luke 2.15

Christmas midday dinner at the grand Hotel. 2-3 Wireless greetings to and from allies all over the world & “peeps” into Christmas parties. 3pm. The King spoke urging brotherhood. He was much less hesitating than usual. We made an early black-out, & by 3.45 we all four were at the Anderstones for tea. Home again n time for 6 o’clock news – chief item this morning at 9 a.m. was the assassination in Algiers of admiral Darlan who came over recently to the allied side though had unfairly at an earlier time slandered Britain as hostile to them the “generous” Hitler!!

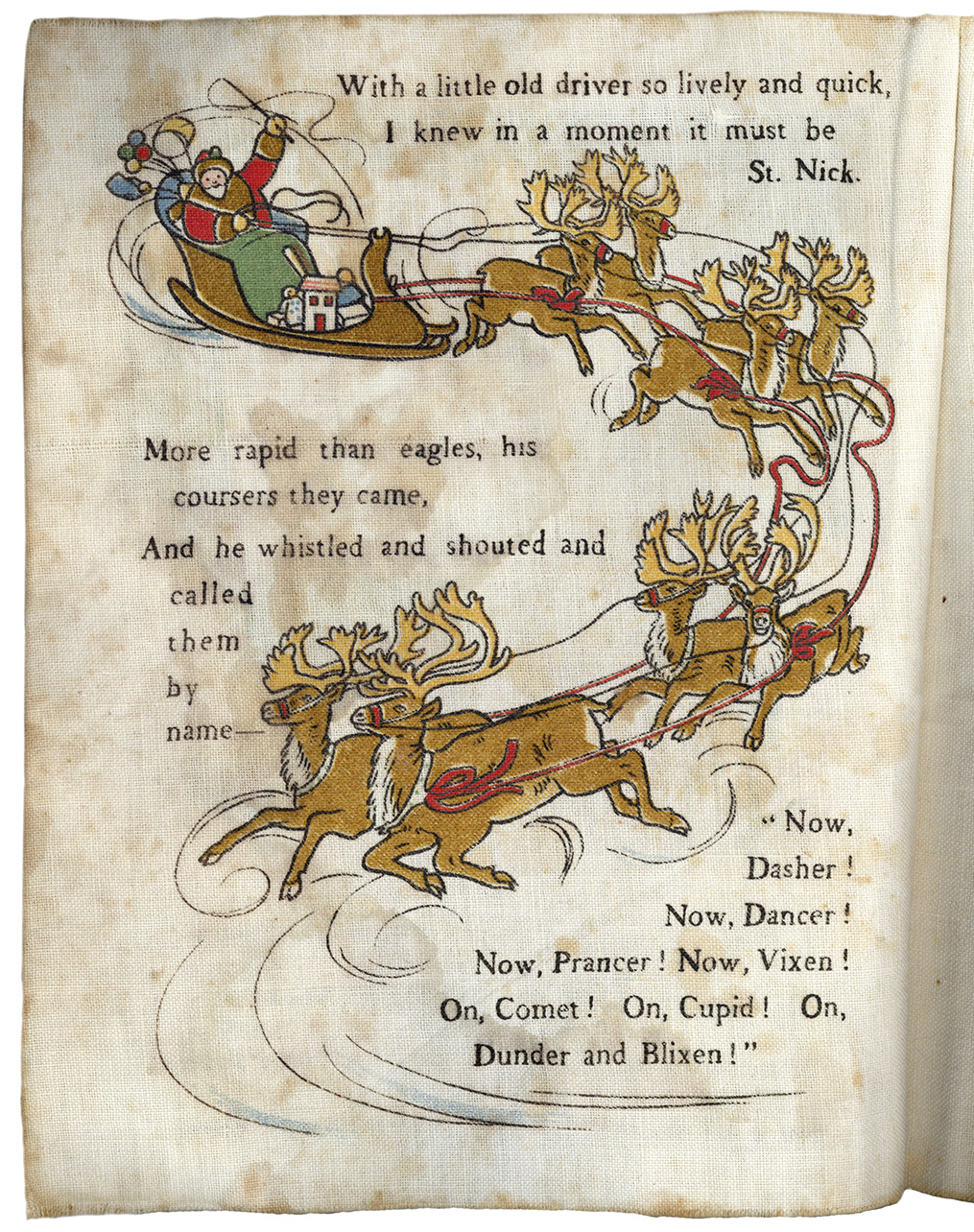

‘The Night Before Christmas’ #ChritmasCountdown Door no.10

Page from ‘The Night Before Christmas‘, 1903 (821.91 MOO)

“The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow,

Gave the lustre of midday to objects below –

When what to my wondering eyes should appear,

But a miniature sleigh and eight tiny reindeer.”

The above image and extract are from ‘The Night Before Christmas’, Dean’s Rag Books Co. Ltd.

‘The Night Before Christmas’ (1903) contains colourful illustrations printed on fabric (also known as rag books) and is sewn up the spine using thread.

Dean’s Rag Books Co. Ltd, was founded in 1903, by Henry Samuel Dean. The company was originally set up to make rag books but soon diversed into rag sheets and soft toys, including teddy bears. During the 1920s and 1930s Dean’s were at the forefront of British bear manufacturing.

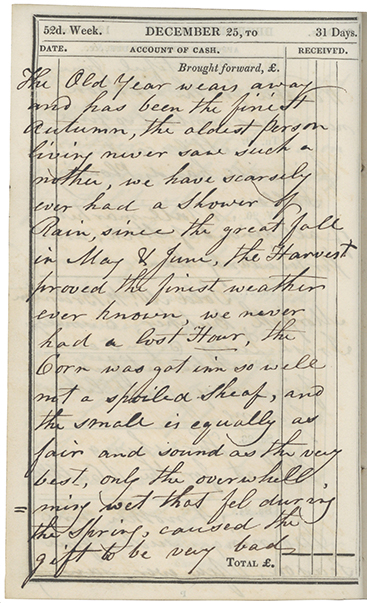

William Brewis Christmas Day, 1843 diary entry #ChristmasCountdown Door no. 9

25th December 1843 diary entry from William Brewis’ diary (Brewis Diaries, WB/1/9)Christmas Day diary extract from William Brewis’ 1843 diary,

The Old year wears away and has been the finest autumn, the oldest person living never saw such another, we have scarsely ever had a shower of Rain, since the great fall in May & June, the Harvest proved the finest weather ever known, we never had a lost Hour, the corn was got in so well not a spoiled sheaf, and the small is equally as fair and sound as the very best, only the overwhell rainy wet that fel during the spring, caused the gift to be very bad

The diaries of William Brewis (1778-1850), farmer, of Throphill Farm, Mitford, Northumberland, cover the years 1833-1850 and are a fascinating compilation of information and anecdotes about farming matters and the local Mitford community. Alongside daily notes of the farming year, Brewis has added comments on local and national events of a political and societal nature.