Richard Grainger and John Dobson are regarded as the main movers behind the development of Newcastle town centre in the 19th century. Dobson is often cited as the main architect for the project. Grainger was the builder who raised the funds for the work and oversaw the building programmes.

During his lifetime, Dobson (9 November 1787 – 8 January 1865) was probably the most noted architect in northern England. He is best-known for his work to develop the centre of Newcastle in a neoclassical style, although he designed over 100 private homes and 50 churches. In 1824 Dobson proposed that Newcastle council create a “civic palace”, with grand squares and wide tree-lined streets on the site of Anderson Place, a large house with extensive grounds. The scheme was hugely expensive and Dobson lacked the financial backing that Grainger was later able to secure for his less grand project.

Richard Grainger (9 October 1797 – 4 July 1861) was an ambitious builder and friend of town clerk John Clayton. Most of Dobson’s Newcastle designs were built by Grainger, including:

Eldon Square (pic)

Still the source of much controversy due to demolition of two of its three faces to free up space for the Eldon Square shopping centre, Dobson produced his Grecian-inspired designs in 1824. Most of it was built by Grainger.

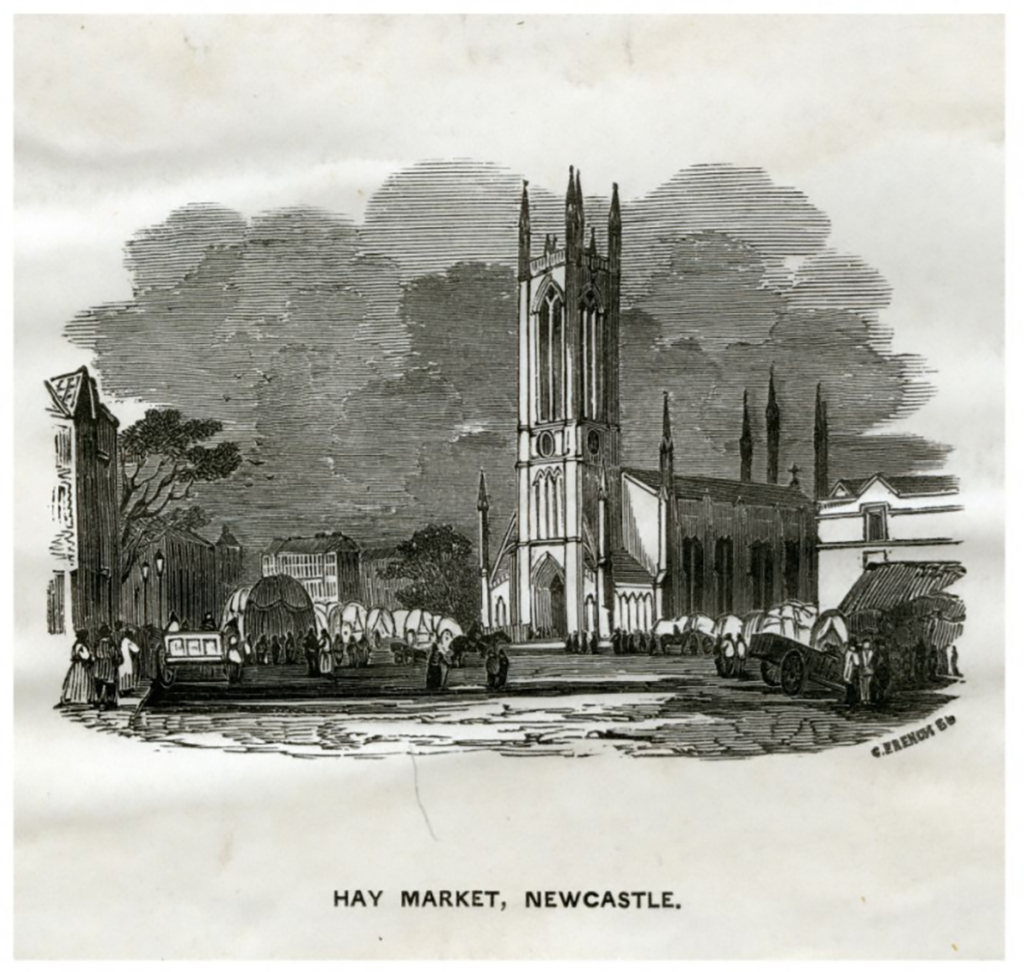

St Thomas’ Church

Built to replace the Chapel of St Thomas the Martyr at the north end of the bridge over the River Tyne, which was demolished by the council to widen the road. Land belonging to St Mary Magdalene Hospital at Barras Bridge was selected as the location for the new chapel. It was designed in a modified Gothic style in 1827 and was completed by 1830 at a cost of £6,000.

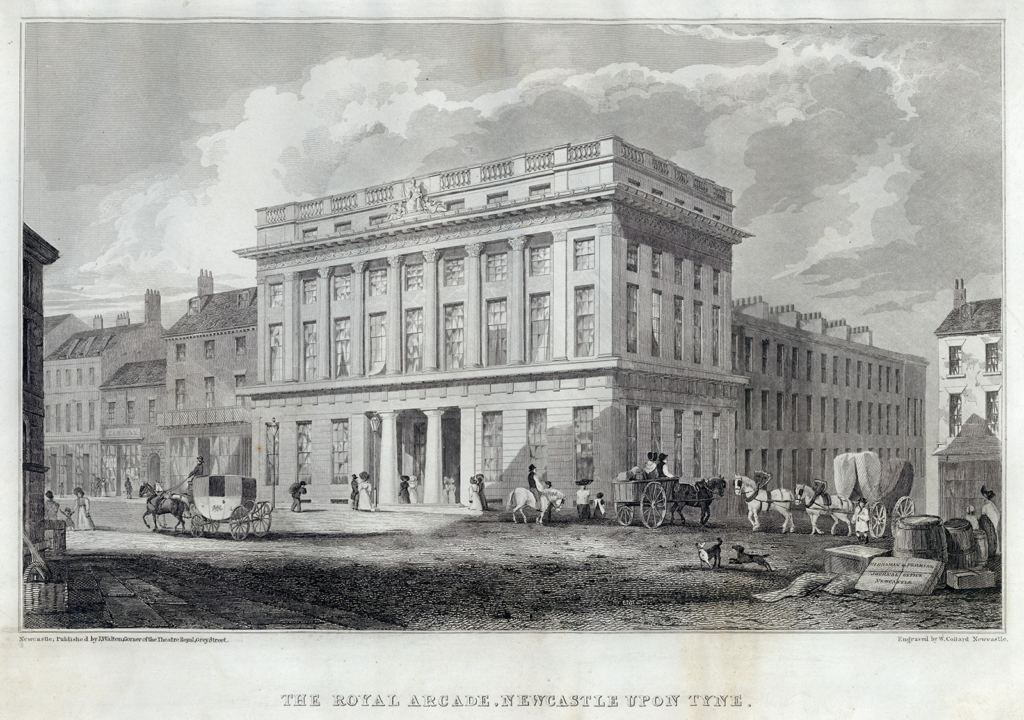

The Royal Arcade

In 1832, the (in)famous Royal Arcade at the foot of Pilgrim Street was completed. Modelled after an elegant London shopping arcade, it was intended as a commercial and shopping centre but was too far removed from the town centre to be a success. Sir John Betjeman, over 100 years later, described the arcade as “a highlight of classical town planning”. Demolition was first suggested in the 1880s, but the Arcade survived until the 1960s when it was cleared to make way for the Pilgrim Street roundabout. The facade was dismantled brick by brick in 1963-64 but plans to rebuild it next to Swan House never happened. The demolition of this building is still a subject of debate to this day.

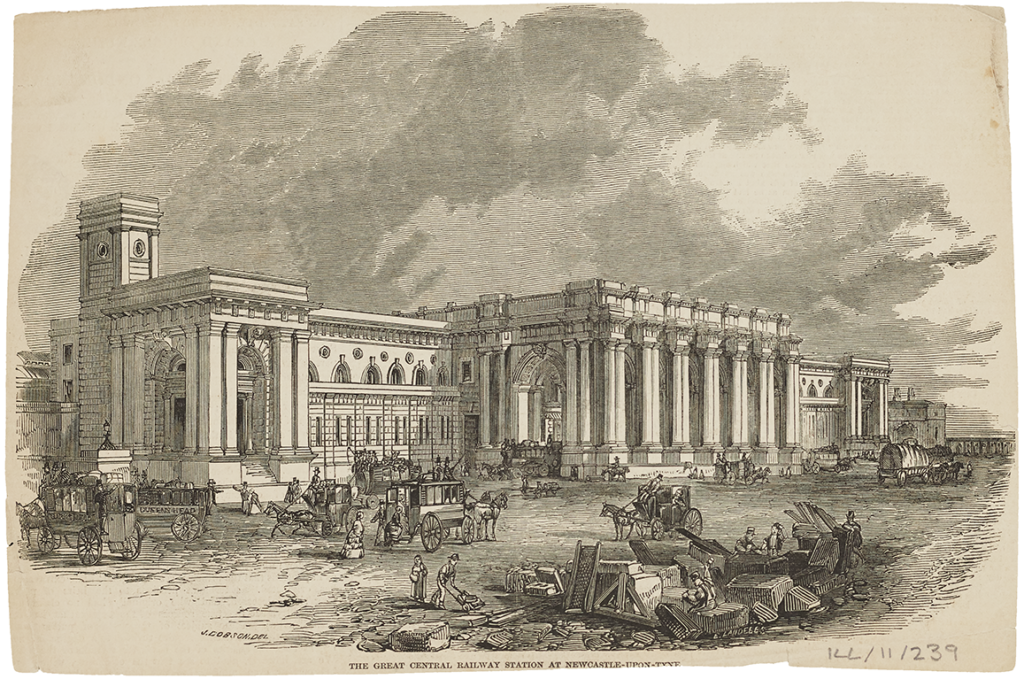

Central Station

After the opening of the High Level Bridge in 1849, a station was required for the thriving town. Dobson’s original plan of 1848 showed an ornate façade with a vast portico and an Italianate tower. The enormous train shed was made up of three arched glass roofs built in a curve on an 800-foot (240 m) radius. Dobson’s design won an award at the Paris Exhibition of 1858 but he was forced to alter his plans to produce a much less substantial portico and remove the Italianate tower. The station was completed in 1850 without the portico. In 1863, Thomas Prosser’s portico was added.

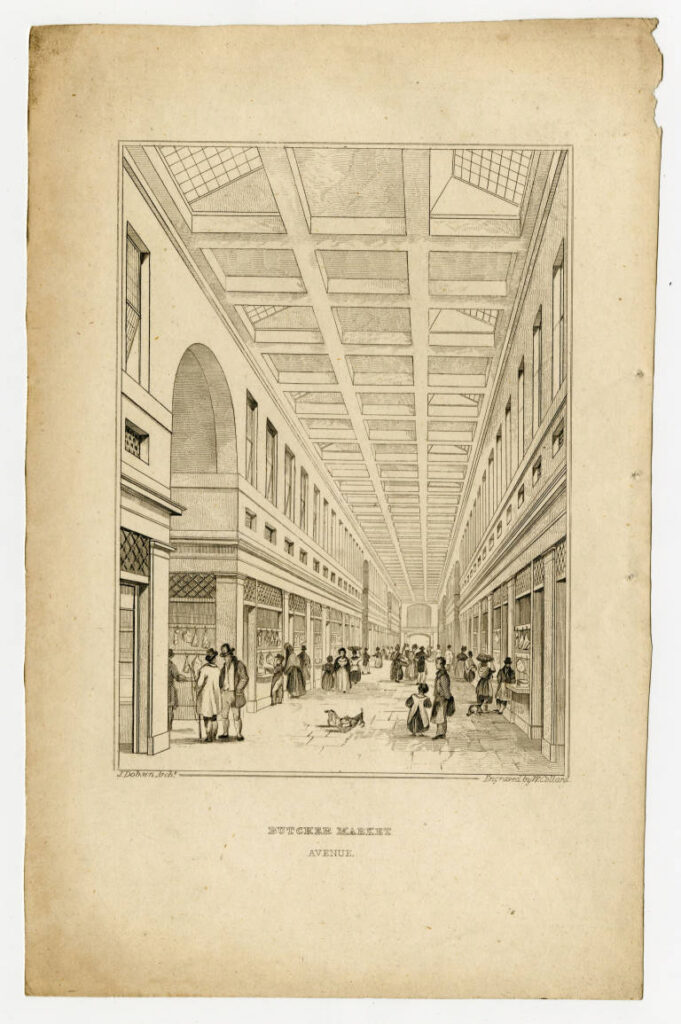

Grainger Market

Grainger offered to build a new meat market and vegetable market to replace the old flesh market. Both new markets were designed by Dobson. The meat market had pilastered arcades, 360 windows, fanlights and wooden cornices, and four avenues each 338 feet (103 m) long. It contained 180 butchers’ shops when it opened. In 1835, to celebrate the opening of the markets, a grand dinner was given in the vegetable market, with 2,000 guests.

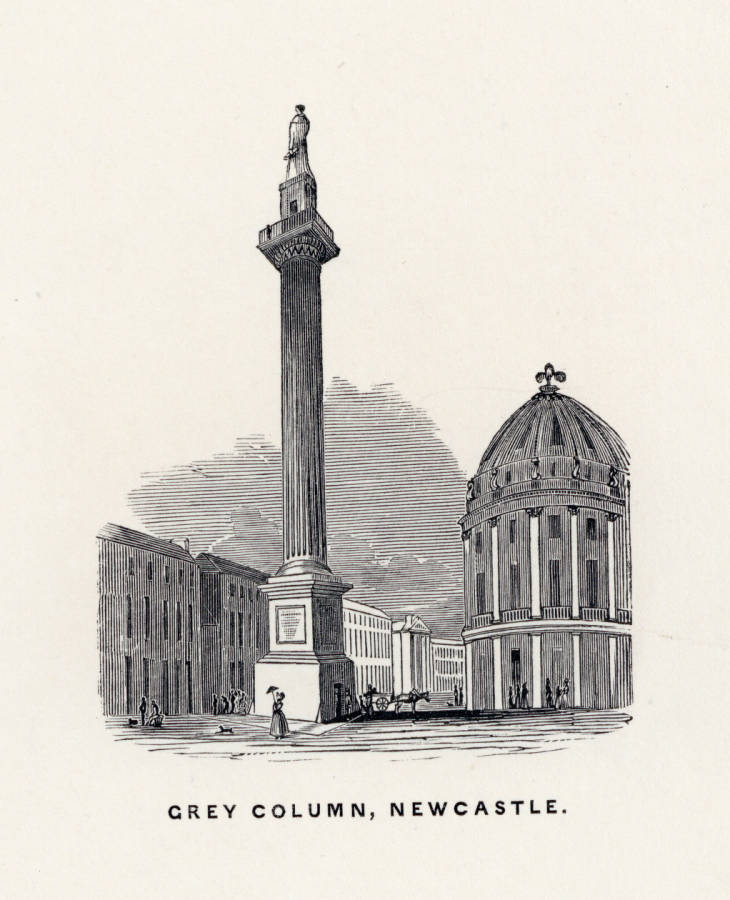

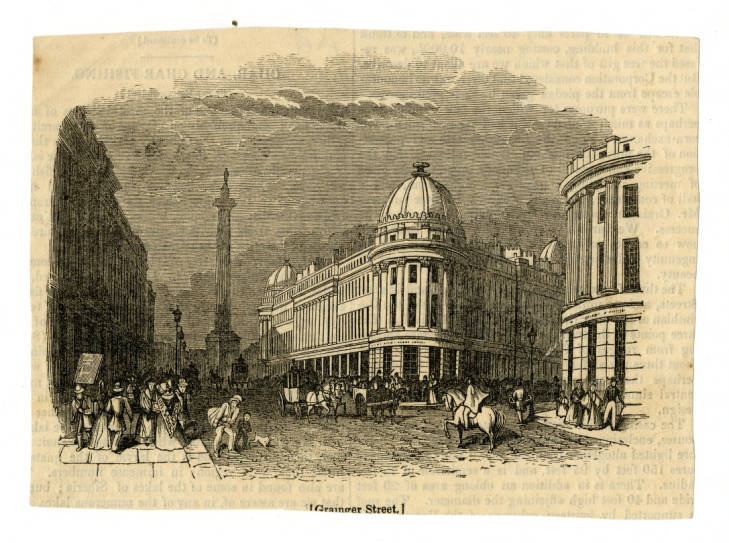

Grainger Town

As mentioned earlier, Dobson had proposed a new town centre to Newcastle council but had been unable to find the funding for his scheme. Grainger secured funds for buying Anderson Place for £50,000 and an additional £45,000 to purchase nearby property with the help of John Clayton. He exercised close control over the master plan for what became known as Grainger Town. Dobson is given much of the credit for the detailed design, but other architects made significant contributions, including Thomas Oliver and John and Benjamin Green. Substantial work was also carried out by two architects in Grainger’s office, John Wardle and George Walker

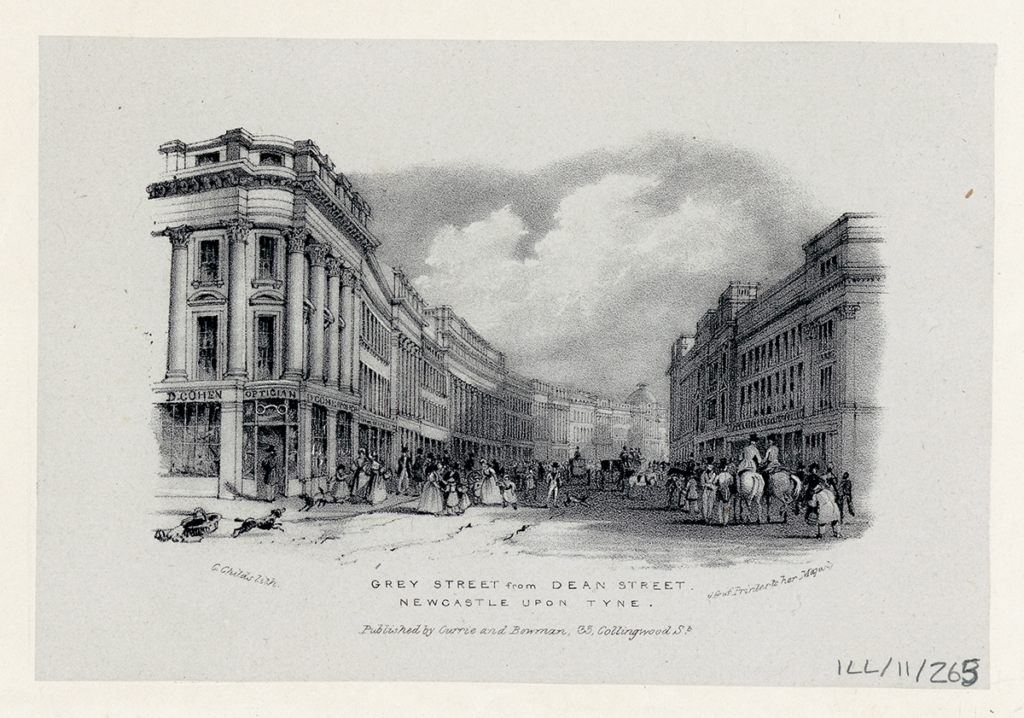

Grey Street

The main thoroughfare in Grainger Town, Grey Street was completed in 1837 and is regarded as the centrepiece of the redevelopment of the centre of Newcastle. The design of Grey Street is often credited solely to Dobson but he only designed the south-eastern side of the street; architects John Wardle and George Walker were responsible for the western side. Prime Minister William Gladstone described it as the country’s “best modern street”.

The West End and the chapel

Grainger received many tributes for his transformation of Newcastle. William Howitt claimed in his 1842 book Visits to Remarkable Places,

“You walk into what has long been termed the Coal Hole of the North and find yourself in a City of Palaces, a fairyland of newness, brightness and modern elegance. And who has wrought this change? It is Mr Grainger.”

Buoyed by his successes, Grainger turned his attention to Elswick, an area to the west of Newcastle, just outside the town boundary. In 1839, he acquired a large area of land there for £114,000, with the intention of building homes, factories, and the city’s major railway station. Grainger moved into Elswick Hall, proclaiming that “Elswick will one day be the centre of Newcastle”.

However, Grainger was already in financial dire straits due to overspending on previous projects. He owed Dobson a large sum of money, which he tried to reduce by charging Dobson £250 for a staircase and ceiling removed from Anderson Place. Dobson was outraged and dissolved their partnership soon after. Grainger, sought the help of Clayton to pay off his debts and left Elswick Hall. He sold the riverside section of his Elswick land to William Armstrong who built up his armaments factory there.

Grainger was correct about the development potential of Elswick; during the second half of the 19th century, the area’s population grew from 3,550 to 59,000 and it became one of the foremost industrial areas of the world.

Grainger died in 1861 at his home at 5 Clayton Street West, Newcastle, and is buried at St James Church, Benwell.

Dobson died at his home on New Bridge Street in 1865, Newcastle, and is buried in Jesmond Old Cemetery.

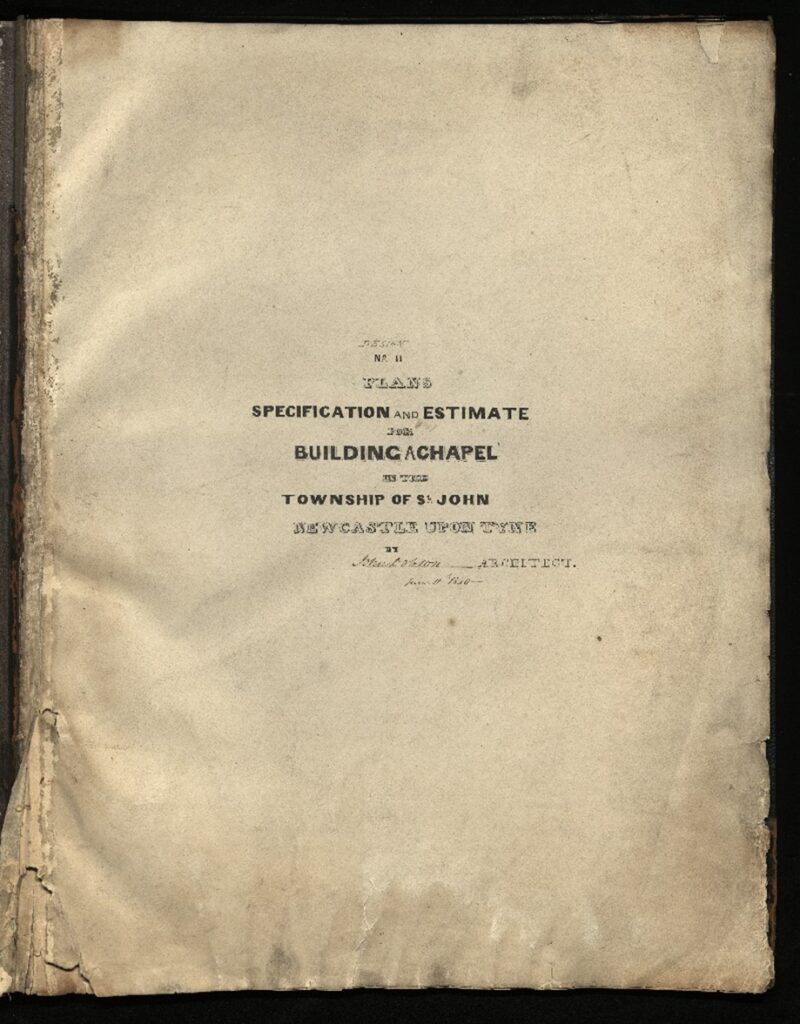

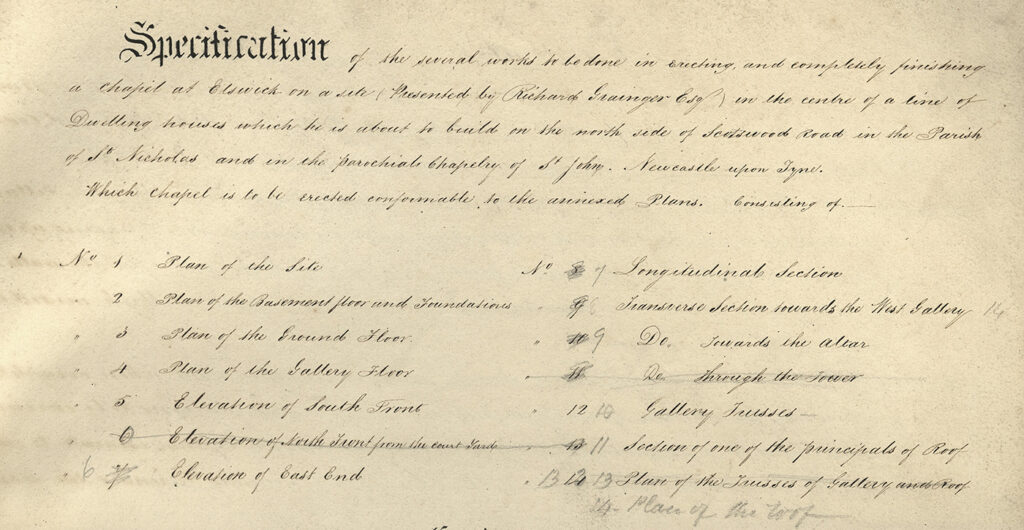

We have recently digitised an 1840 manuscript volume of plans produced by John Dobson for a chapel for Richard Grainger. The full manuscript is digitised and available to view on CollectionsCaptured titled Design No. II: Plans, specification and estimate for building a chapel in the township of St. John, Newcastle upon Tyne.

The title page and introduction are shown below.

The first paragraph informs the reader that this is a,

‘Specification of the several works to be done in erecting and completely finishing a chapel on a site Presented by Richard Grainger Esq. in the centre of a line of Dwelling house(s) which he is about to build on the north side of Scotswood Road in the Parish of St. Nicholas and in the parochial Chapelry of St. John, Newcastle upon Tyne.’

The chapel was probably part of Grainger’s Elswick scheme.

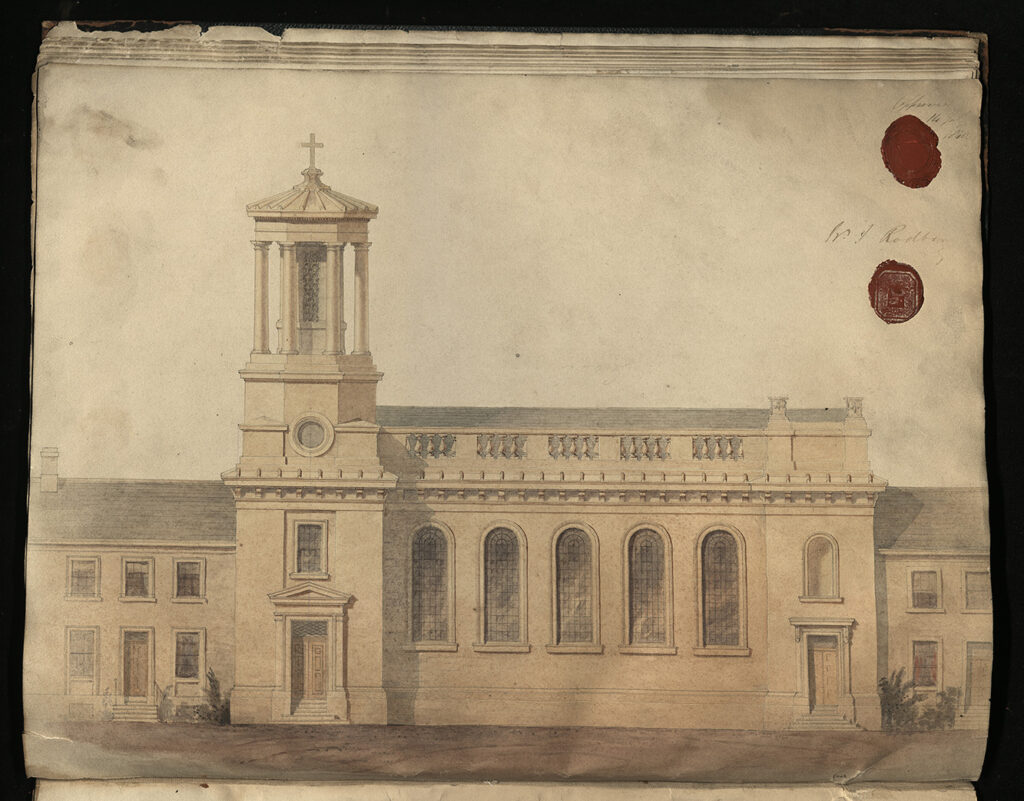

The manuscript contains plans, specifications and estimated costs for the construction of a chapel for Grainger’s site. Within the handwritten volume are pencil annotations, modifications to plans, and other markings and wax seals. There is also a watercolour visualisation of how the finished chapel may have looked. The item is on permanent loan from the Northern Architectural Association, whose first president, in 1859, was John Dobson.

This item was presented by Hicks & Charlewood, architects. William Searle Hicks (1849-1902 was President of the Northern Architectural Association between 1891-1892. In 1885, he went into partnership with Henry Clement Charlewood (1856-1943). Charlewood was President of the Northern Architectural Association between 1910-1911.

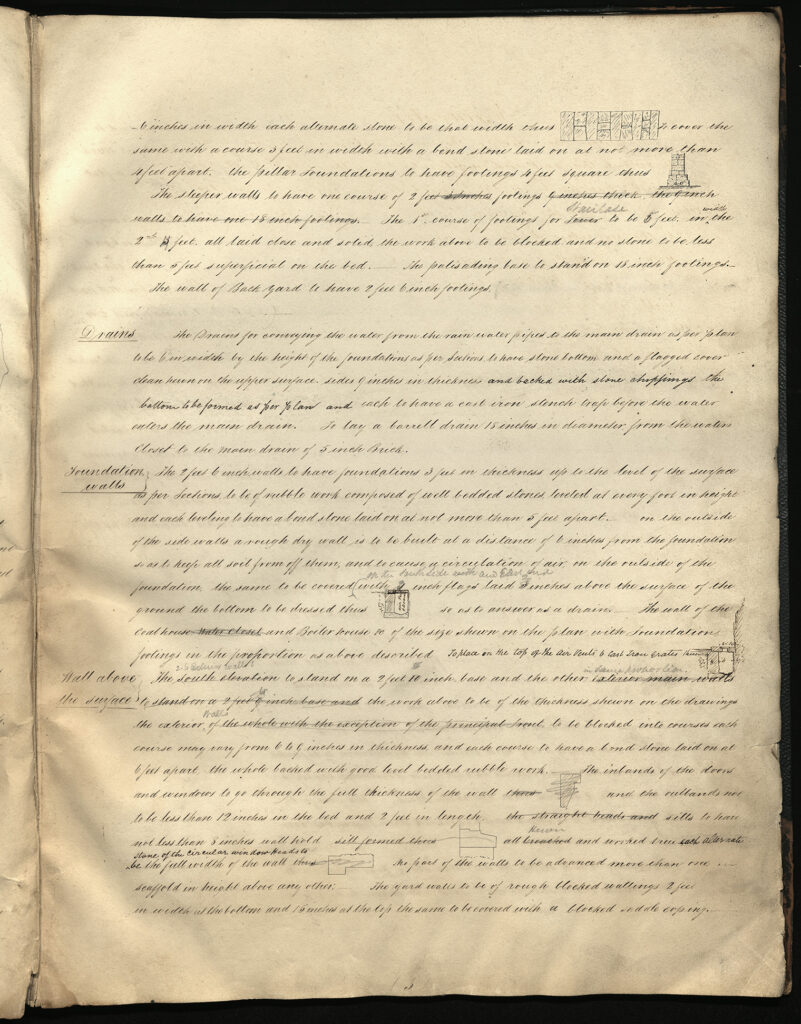

The text is all handwritten and gives instructions as to the construction of the chapel, which was designed to seat 1064 people. It describes construction, and specifies where materials are to be sourced. This includes wood from Gottenburg, Memet or Riga, and Welsh lady slates. However, some materials could be found closer to home,

‘The mortar to be made of the best stone lime from Cleadon, Whitley, or Allawash and the best sharp sand from the mouth of the Derwent River, in the proportion of one part of lime to two parts of sand.’

Cleadon is just south of South Shields and remains of the quarry are still visible. All plastering was to be done with Cleadon lime. Whitley (now Whitley Bay) Quarry is now occupied by Marden Quarry and stretched to the site of Whitley Bay Cricket Club pitch. Before the establishment of the railways, Whitley Quarry was probably the biggest lime producer in Northumberland. By 1850 it was in decline, with the flooded portion in use as a reservoir. There were (and still are) numerous quarries near Allerwash, Newbrough, and Fourstones in the Tyne Valley.

For the glazing, Dobson specifies the use of ‘Newcastle 2nd Crown glass’. Crown glass manufacture was one of the two most common cheap processes for making window glass until the 19th century. It had a distinctive disc-like appearance, common in church windows.

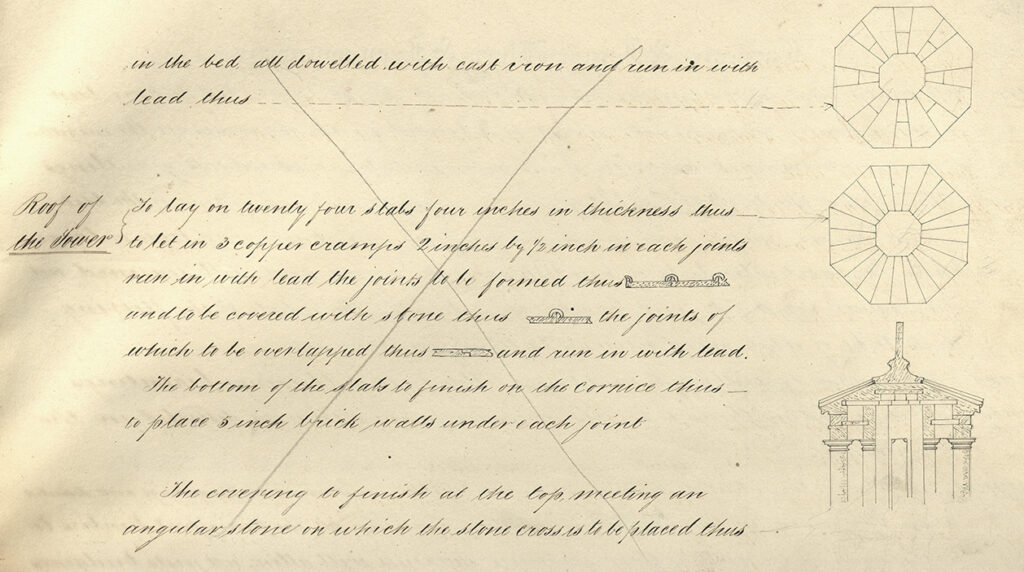

Within the hand-lettered specifications are drawn diagrams showing how individual parts of the chapel should be constructed.

To provide an easy-to-understand representation of the chapel, there is a watercolour visualisation of the building.

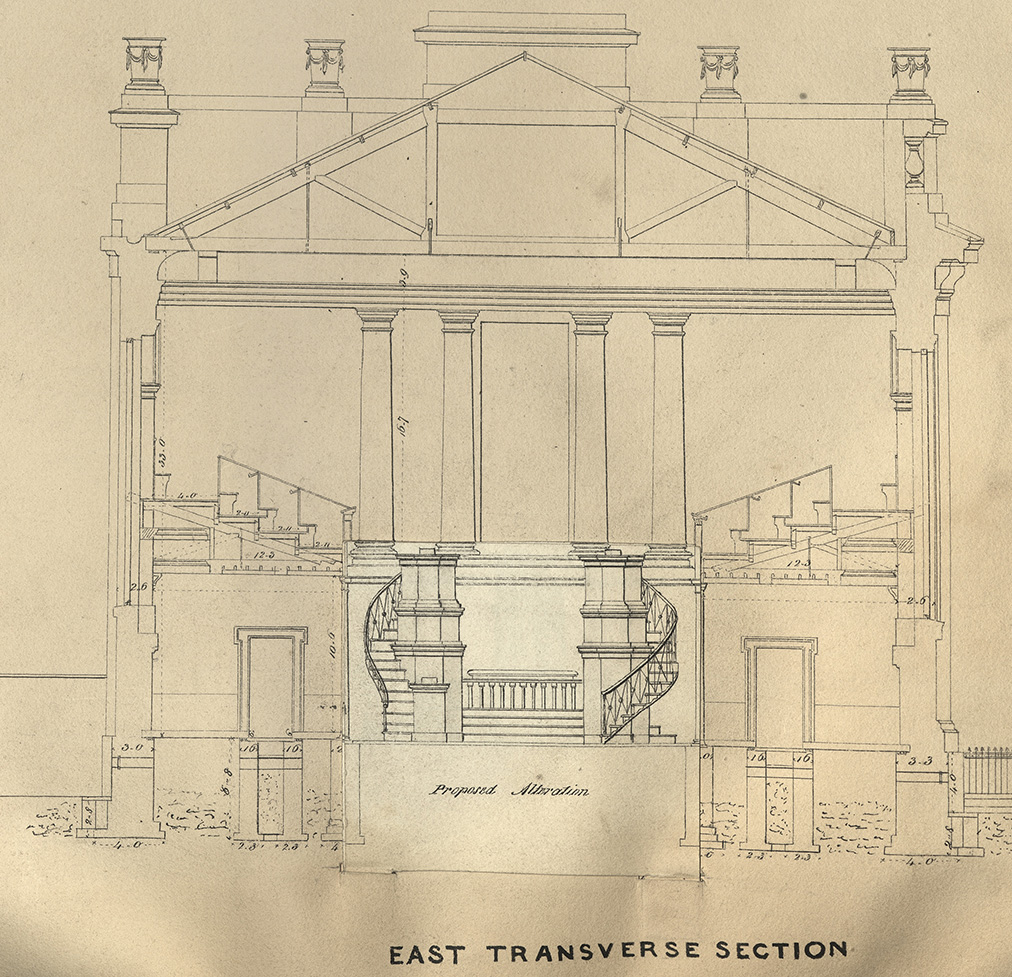

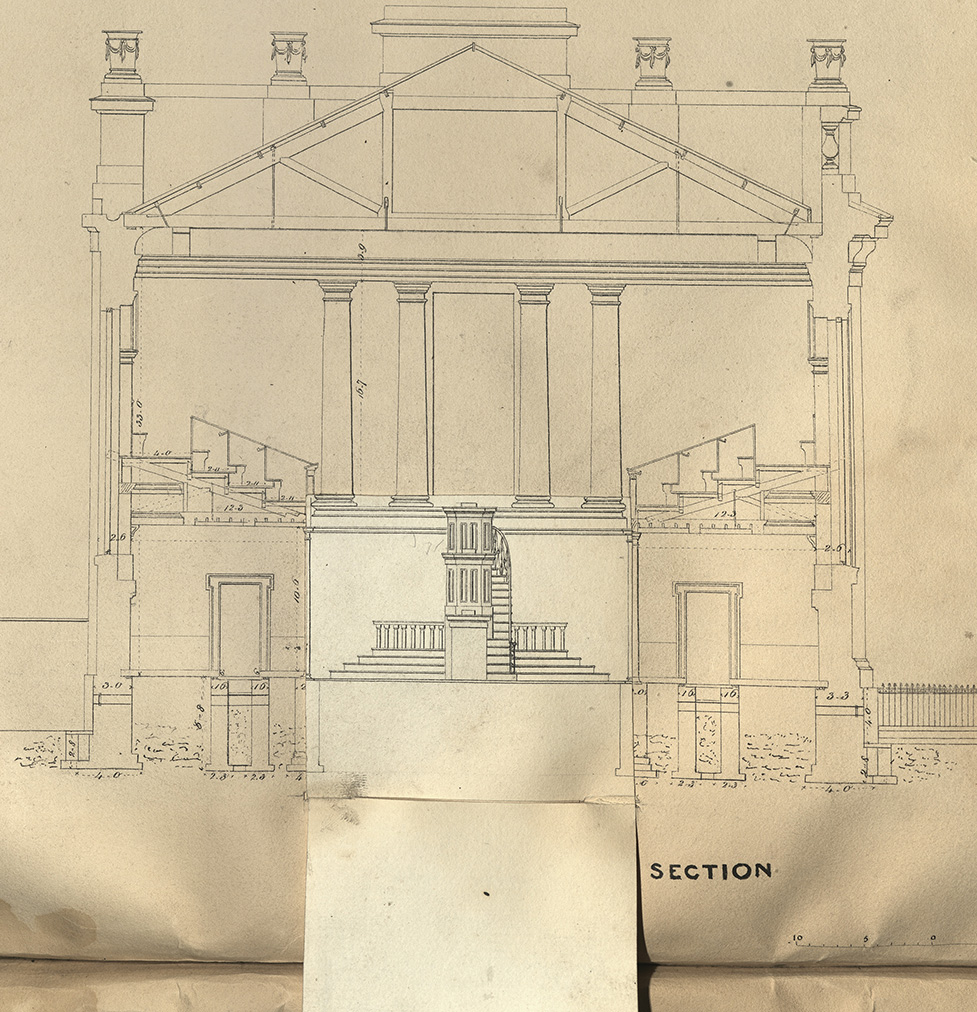

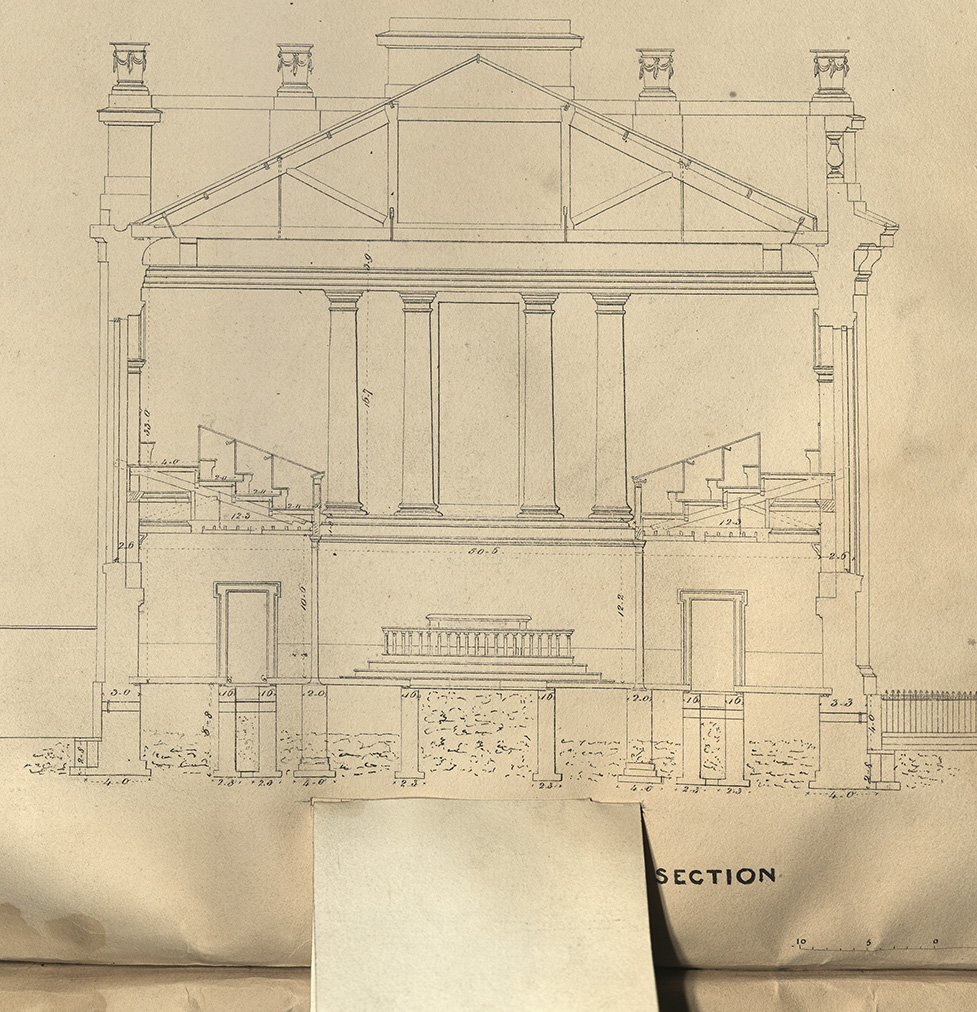

One of the most ingenious devices in the manuscript can be found on the page showing the plan of the east transverse section. This has two overlay flaps with changes or alternative designs for that portion of the chapel. As the chapel was never completed, we do not know which variation was selected!

The images above show a plan with overlay flaps showing alterations or alternative designs from Design No. II: Plans, specification and estimate for building a chapel in the township of St. John, Newcastle upon Tyne (Rare Books, RB-726.41 DOB).

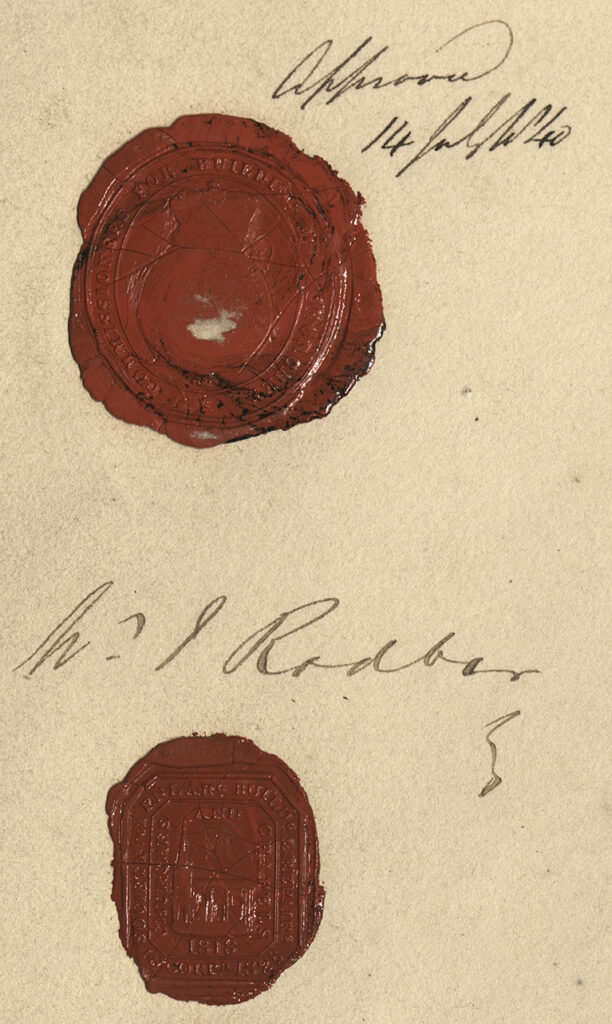

The seals

The specification, estimates, and plans were approved on 14th July 1840. Each approval is accompanied by two wax seals and a signature. The seals reveal bear the name of the COMMISSIONERS FOR BUILDING NEW CHURCHES. The signature is of W. J. Rodber, who was secretary of the Society for Promoting the Enlargement, Building and Repairing of Churches and Chapels. This organisation was founded in 1818 to provide funds for the building and enlargement of Anglican churches throughout England and Wales. The Society required building request applications to be submitted in a consistent and uniform fashion, with drawings and plans of the proposed work. So, in addition to providing Grainger with plans and costings, this is possibly also the purpose of these detailed chapel plans.

(Rare Books, RB726.41 DOB).