Nothing about the title of this post is original. The main title imitates that of an essay by historical sociologist Margaret Somers called ‘Let them eat social capital’, which appeared in 2005. The subtitle and the idea of a genealogy of concepts that situates them in a larger political context draws on an essay by Nancy Fraser and Linda Gordon called ‘A Genealogy of Dependency’, published in 1994. That essay dealt with a word that became current in debates leading up to US social policy changes signed into law in 1996 by then-President Clinton. Those so-called reforms ended a decades-old guarantee of at least minimal income support to households with dependent children that was already among the least generous in the high-income world. In many cases, the destructive effects, in particular those of draconian and arbitrary ‘sanctioning’ regimes, were uncannily similar to those that followed more recent changes to benefits eligibility in the UK. I cannot achieve the depth or sophistication of Somers’ or Fraser and Gordon’s analyses. But I do hope to stimulate critical thought about both the underlying, often unexamined assumptions of the public health vocabulary, and about the policy implications.

The concept of resilience is used in multiple ways and multiple contexts. For public health, three are probably most relevant. The first involves disaster planning. I won’t explore that further here, although important political dimensions that parallel the argument I will present are suggested by social scientists who have studied responses to events like the 1995 Chicago heat wave and Hurricane Katrina a decade later. (In the words of an excellent book on the New Orleans experience of the hurricane, There Is No Such Thing as a Natural Disaster.) The definitions on which I will focus are, rather those put forward by psychologist Michael Rutter and by a Canadian research group on resilience in communities.

So, first, Michael Rutter: ‘The term resilience is used to refer to the finding that some individuals have a relatively good psychological outcome despite suffering risk experiences that would be expected to bring about serious sequelae. In other words, it implies relative resistance to environmental risk experiences, or the overcoming of stress or adversity’ (citations omitted). There are similar definitions in the literature that are not restricted to psychological outcomes.

Then, second, the Canadian group’s take: ‘Resilience is the capability of individuals and systems to cope successfully in the face of significant adversity or risk. This capability develops and changes over time, and is enhanced by protective factors within the individual/system and the environment, and contributes to the maintenance or enhancement of health’.

Immediately we see why the conceptual unpacking that is essential is also so difficult. Who would want individuals not to have good outcomes after risk experiences? Who would not want communities to cope successfully, however that is defined, in the face of adversity?

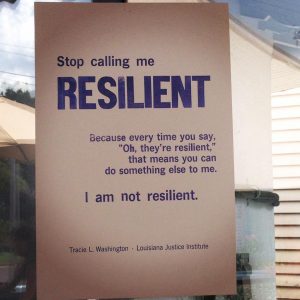

My central argument – the take-home message, as the bureaucrats say – is about the need for political awareness and methodological self-consciousness. A focus on resilience diverts attention from a more important question: the sources of risk experiences and adversities; the political choices that variously drive them, sustain them and magnify them; and the all-important question of who benefits from those choices. In this, as in other work on the politics of health, I draw on an important analysis by Finn Diderichsen and colleagues, who argued the need to locate the origins of health inequalities with reference to ‘those central engines in society that generate and distribute power, wealth, and risks’.

I do not for a moment suggest that resilience is used in public health research in the way that dependency was used in the intellectual racketeering that infused the welfare reform debates. I do think that the quest for sources of resilience, and the implicit ascription of responsibility that it entails, unavoidably shifts the focus of research, policy analysis and professional practice away from the ‘central engines’ referred to by Diderichsen and colleagues. This is entirely congruent with a central element of the neoliberal ideological project and policy agenda. Political scientist Jacob Hacker, writing in the US context, has called this The Great Risk Shift: whilst economic policy generates new forms and levels of insecurity, these are not understood as requiring public or collective responses of the kind exemplified in the United Kingdom by the creation of the National Health Service. Rather, public policy and public understanding regard these risks as matters of individual or localized responsibility; risks are no longer to be shared, and cross-subsidies are anathema; they simply reward the undeserving. In 1998, Anthony Giddens (in)famously wrote about replacing the welfare state with a social investment state, in order ‘to develop a society of “responsible risk takers”.’ For many people, this has meant replacing the welfare state with a no-second-chances state. Social scientists should take the latter concept more seriously.

An example of the discursive shift I am talking about: one of several articles from a research programme organised around the concept of community-level resilience explored the characteristics of economically disadvantaged Parliamentary constituencies with relatively low mortality rates relative to other constituencies with similar levels of disadvantage. The authors identified this policy implication: ‘If some areas can resist the translation of economic adversity into higher mortality, other areas can learn from their policies and approaches, so that they are better protected when economic recessions arrive’.

Note the language here: economic recessions ‘arrive’, like the swallows at Capistrano; there is no suggestion that recessions reflect either exercises of economic power or the consequences of past policy choices. The article in question appeared in 2007, so this latter point is of special significance given what we learned shortly afterward about the inequitable global reach of negative externalities associated with financial deregulation in a few high-income countries.

A focus on resilience at the individual level diverts attention from the realities of life on a low and precarious income, and from the fact that in much of the high-income world – certainly in the United Kingdom – whatever opportunities for ‘overcoming stress or adversity’ people living in such circumstances might have are being cut away at the community level. Far from reinforcing capacities that might sustain resilience, post-2010 public policy in the United Kingdom has systematically attacked them, notably draining resources from both local economies and local authority budgets.

For example, researchers at Sheffield Hallam University’s Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research (CRESR) have shown that by 2021, post-2010 benefit reforms will be sucking close to £1000 per working-age person per year out of some of the poorest local authority areas in Britain. That is an annual impact, on areas some of which are poorer than any regions elsewhere in northern Europe. The impacts on households’ ability to pay the costs of daily living have been devastating, driving many deeper into debt and into reliance on food banks. The effects have been exacerbated by cuts in central government funding to local authorities, crippling services that are disproportionately relied upon by those on low incomes whilst having little or no effect on affluent residents of leafy places. Almost 30 years ago, former US politician Robert Reich characterised this pattern as the ‘secession of the successful’.

If one tried to design a strategy of undermining the ability of local areas or communities to resist the ‘translation of adversity into higher mortality’, it would look quite a lot like post-2010 governments’ approach to providing social protection and financing local government.

I presented a less well developed version of this argument late in 2014, at a National Institute for Health Research School for Public Health Research annual scientific meeting. (Its content may explain why I have not been invited back.) Unbeknownst to me Public Health England, whose website describes it as ‘exist[ing] to protect and improve the nation’s health and wellbeing, and reduce health inequalities’, was then in the process of publishing a set of priorities that called for ‘developing local solutions that draw on all the assets and resources of an area, integrating public services and also building resilience in communities so that they take control and rely less on external support’. This, after many years of debilitating policies that redistributed economic resources upward and to wealthier regions of the country.

What else is there to say?

To restate the point: the concept and vocabulary of resilience subtly but inexorably direct attention – and assign responsibility for ‘taking control’ – to people and communities who suffer the consequences of choices made and policies adopted far away, over which they had little or no control. In stage magic, this is called a misdirection: it distracts the audience from what is really going on. That may not be the intention, but it most certainly is the effect. Public health researchers and practitioners have a professional responsibility to see through the deception, and to help others to do the same.