In a recent post, I observed that some of the trees in the memorial at The Angel have been marked as the ‘plot’ of an individual family, making the site feel increasingly like a more formalised cemetery or graveyard. At the heart of the wooded copse, immediately beneath The Angel, an alder tree has been surrounded by a small wooden fence and a metal plaque has been placed into the ground, inscribed with the name of a family’s daughter. This tree at the centre of the memorial garden, which commemorates a little girl, represents for me the emotional heart of the site.

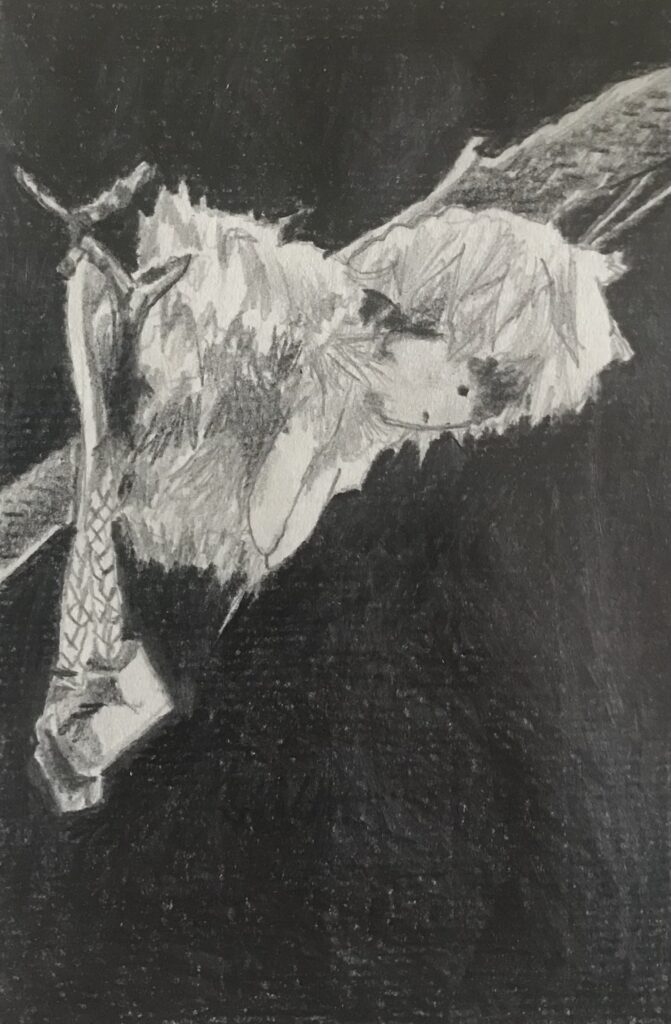

I do not know the girl’s surname, or her story. I only know her through this memorial tree. Over the few years that I have visited the memorial site at The Angel, the child’s family have decorated the tree each year on her birthday with tokens of the gifts they would have given her, including a birthday balloon which records that she would have been three, and then four, years old. I have found it moving to witness these tributes, both because of the parents’ ongoing ritual of remembrance, and because of the evident care with which the objects have been chosen and placed. The annual decoration of the tree takes place in the winter months, and the bare branches of the alders mean that The Angel is clearly visible above.

This tree raises questions for me about how I represent the memorials at The Angel, which are at once both public and private. The tree is so central to the memorial site – both physically and emotionally – that I do not feel I can tell the story of the grassroots memorial without documenting it. At the same time, there is a sensitivity in relation to it, because of the nature of the grief that it represents.

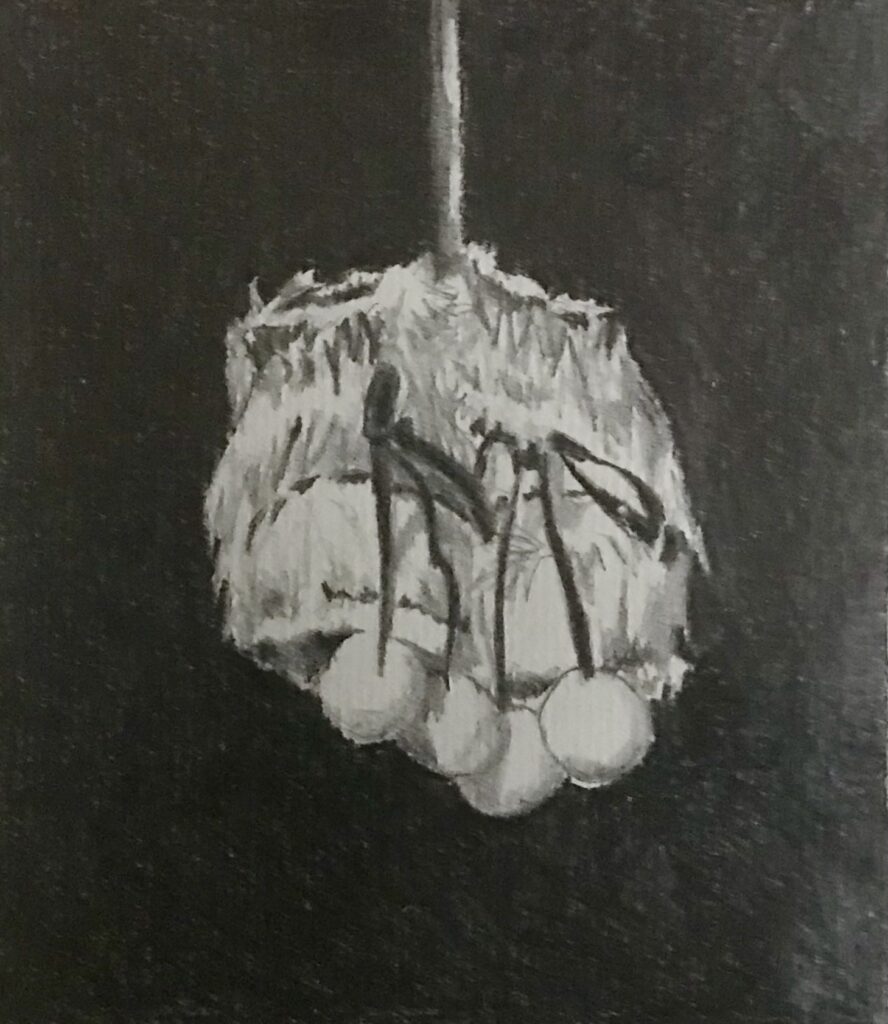

In an earlier post, I wrote of artist Miriam de Burca, whose work records the cillini: memorial sites in Ireland, which were burial grounds for those deemed unworthy of an official grave, including babies and children who had died before baptism. De Burca makes meticulous and detailed drawings of clods of earth from these remote and hidden sites, which she digs up, draws in her studio, and then returns to the site once the drawing has been made. De Burca’s drawing represents not only an act of recording, but also a quality of attention. The drawing takes time – it is not the instant image of the photograph – and it requires a sustained and careful process of observation.

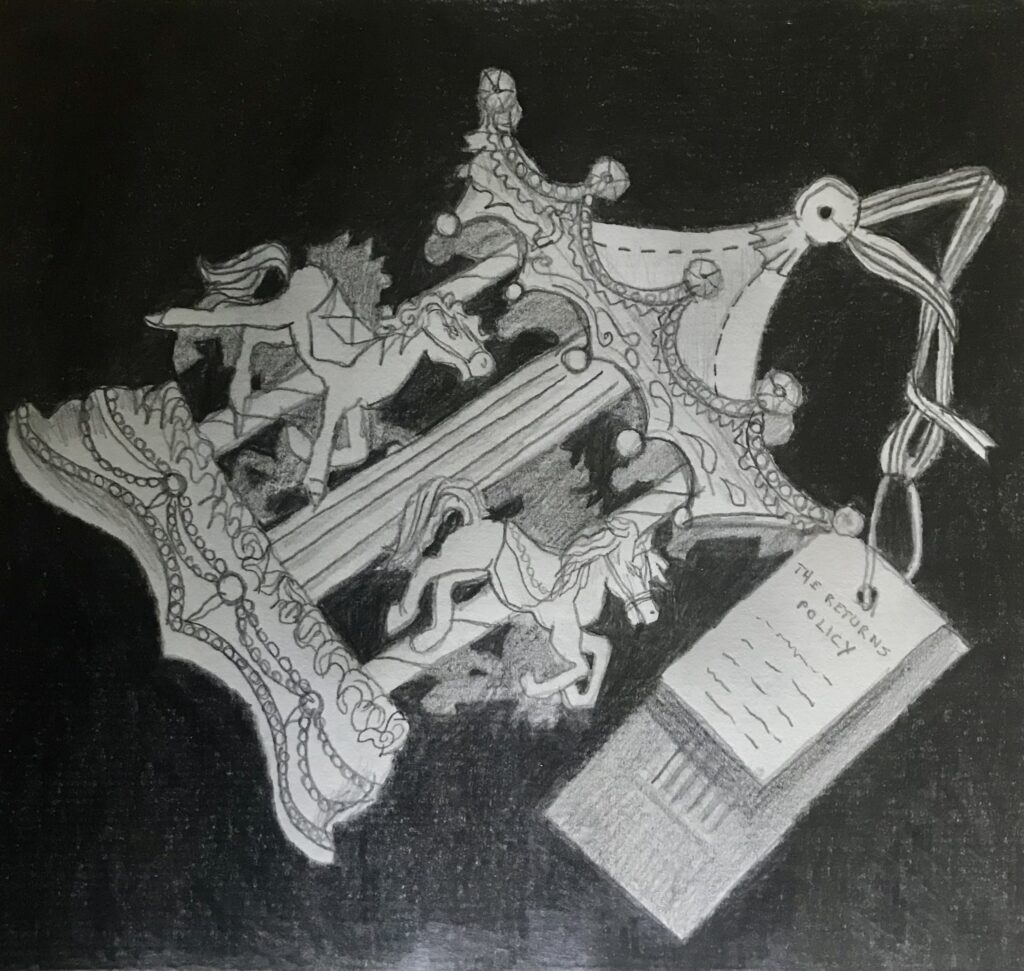

Following de Burca’s lead, I have chosen to draw the tributes on this tree, with each pencil sketch taking several hours to complete. I hope that these works, which record just a selection of the many objects left on the tree, both recognise and honour a family’s acts of love and remembrance.

I have pointed out in a previous post that, while objects that are left on The Angel sculpture tend to be moved, the tributes left in the trees usually remain in place, disturbed only by the wind. This is true of the objects suspended from this tree, which visitors will often hang from its branches again if they are blown to the ground. On a recent visit, a toy monkey, which had been left at the side of the path leading out of the trees and which was getting muddy in the rain, had been placed in the fork made by two branches of the tree. This gesture protected the toy, and its positioning suggested that other visitors had also been moved by the memorial, wishing to leave their own gift for the little girl alongside those of her family.

In a moving piece of writing, Marcus Weaver-Hightower – the father of a stillborn baby, Matilda – reflects on the importance of things to parents who experience baby loss. He writes that material objects connected to the baby can help parents to resist ‘a pressure from others to forget (get over it)’, as well as offering a focus when there is ‘a lack of adequate quantities of memories and few people who share these memories’ (476). Weaver-Hightower adds that some parents actively create memories by buying new toys and other baby things, which can ‘provoke memory’, and which ‘might be kept in private or publicly displayed’ (476). His words chime with the memorial rituals that I have observed at the tree beneath The Angel, and my drawings of some of the tributes that have been left there seek to register their affective power, not only for the family but also for those who visit the site and encounter them.

References

Marcus Weaver-Hightower, ‘Waltzing Matilda: An Ethnography of a Father’s Stillbirth’, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 41.4 (2012), 462-91.