This post forms part of a monthly series that documents the plants growing at The Angel of the North through a series of cyanotypes.

July sees two flowers in bloom at the Angel site that have commemorative significance relating to the two World Wars. The pink spires of the rosebay willowherb wave in the breeze, and this plant is closely associated with the bombed-out sites of World War Two, when it proliferated on the fire-scorched ground. Poppies are also in flower, and this plant has become synonymous with the national commemorations of the First World War.

Rosebay willowherb, otherwise known as fireweed, thrives on waste ground, and particularly on burned-over land, because fire and other disturbances cause its seeds to germinate. Considered a rare species in Britain in the eighteenth century, it took hold here during the Industrial Revolution, particularly along the railway lines, where the associated soil disturbance, combined with the wind dispersal of the seeds by passing trains, created the ideal conditions for it to flourish. Even today, the rosebay willowherb’s purplish-pink flowers are a ubiquitous sight from train windows, spreading along the route of the track.

The bombing campaigns of the Second World War, and especially the widespread fire damage, caused the rapid spread of rosebay willowherb across bomb-damaged sites, earning it the nickname of bombweed. The children’s novel Fireweed is set during the Blitz, and centres on the bomb sites where the plant grew profusely, while Cicely M. Barker’s 1948 book Flower Fairies of the Wayside includes the following verse for the Rosebay Willowherb Fairy:

When the earth is burnt and sad, I will come to make it glad. All forlorn and ruined places, all neglected empty spaces, I can cover – only think! – with a mass of rosy pink.

In 2002, the rosebay willowherb was chosen as the county flower of London, to mark its role in clothing in magnificent purple the bomb-scarred areas of the City, as it slowly recovered from the derelictions and deprivations of war.

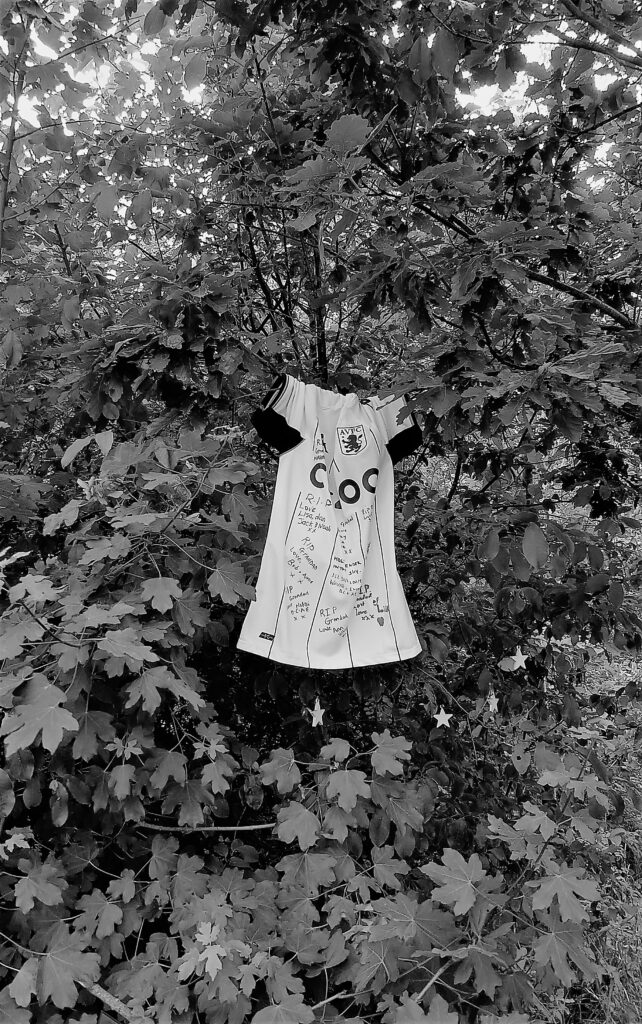

The cyanotype of the rosebay willowherb above cannot capture its distinctive colour, but it does highlight the sculptural form of its tall spire. The site of the Angel of the North has not been fire damaged, but it is highly disturbed ground that has been landscaped from the waste land left behind by the former coal mine. The presence of the plant registers the industrial history of the site, and its reclamation from brownfield land.

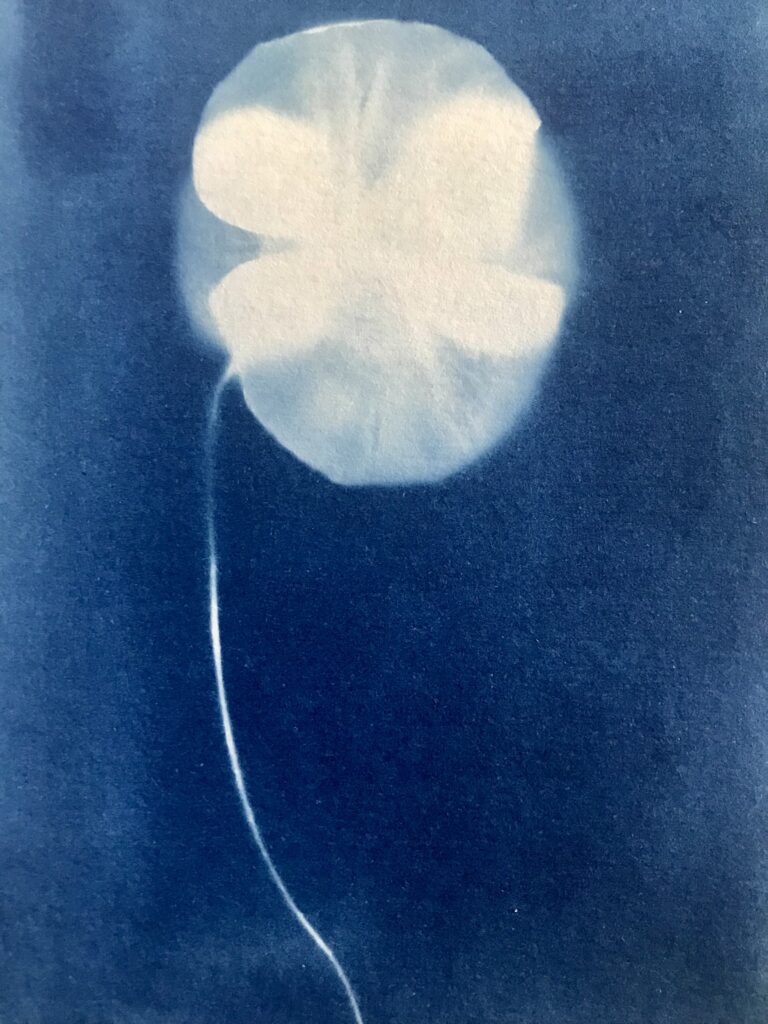

This cyanotype of a poppy growing at the Angel enhances its ghostly fragility, as the thin outer petals allow the light to pass through, creating a semi-opaque halo effect. The image seems appropriate to the flower’s status as an icon of remembrance.

Poppies have long symbolised sleep and death: sleep because of the somnolent effects of the opium that can be extracted from them, and death because of the blood red of the flower. In ancient Greek and Roman culture, images of poppies inscribed on graves represented eternal sleep and poppies were commonly used as offerings to the dead. The common poppy became a symbol of remembrance for the First World War in Britain and the Commonwealth nations, because it thrived in the disturbed land of the European battlefields. The connection of the poppy with remembrance was reinforced by the famous poem ‘In Flanders Fields’ by the Canadian soldier and surgeon John McCrae, and artificial poppies were adopted to commemorate those who had died in war in the UK, Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. The ritual of wearing the poppy centres on Remembrance Day on November 11, and in New Zealand and Australia, soldiers are also commemorated on ANZAC Day, which falls on April 25.

The poppy as a token of remembrance resonates with the memorial site at the Angel, as well as with the memorial aspect of the sculpture itself, which commemorates those who lost their lives in the mining industry. Like the rosebay willowherb, the poppy flourishes on disturbed ground and it is this feature of the plants that has made them so closely associated with the bomb sites and battlegrounds of the twentieth century. Looking at the soil in which these plants grow, as well as at the flowers themselves, their presence at the Angel site acts as a marker, not of the catastrophic events of war, but rather of the long industrial and post-industrial usage of this land. It is plants such as these, which are tolerant of disruption and low fertility, that are able to proliferate in the conditions created by such activity.