Sounding the Angel can now be accessed in full here. In a series of four blog posts, I introduce each of the four sections of the sound work. Today’s post discusses the third part of the work, ‘Spring’. You can listen to this section here. In this instalment, I focus on the participants’ experience of returning to The Angel after they had placed the memorial tribute there. I ask: What is the ongoing relation to the place?

Our first participant returned to The Angel one or two weeks later, to see what – if anything – remained of the tribute. On this occasion, the weather was fine and the site was busy, with bus trips and a group of people in the memorial garden. He had chosen the same time of the week to go back, and the man who had been there on the first occasion was out walking his dog again. As our participant expected, there was no trace left of his memorial tribute, and he took a photograph of the place where it had been. He found comfort in the knowledge that his wife would have approved, as well as in the idea of The Angel becoming her guardian.

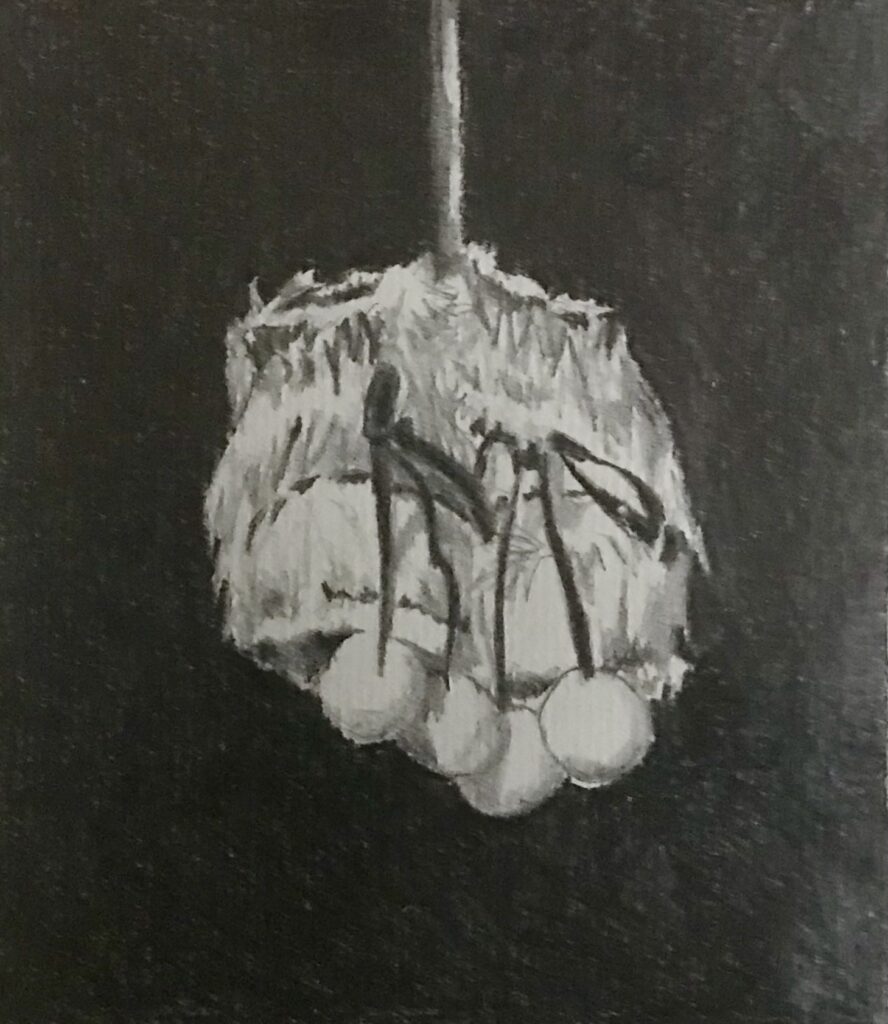

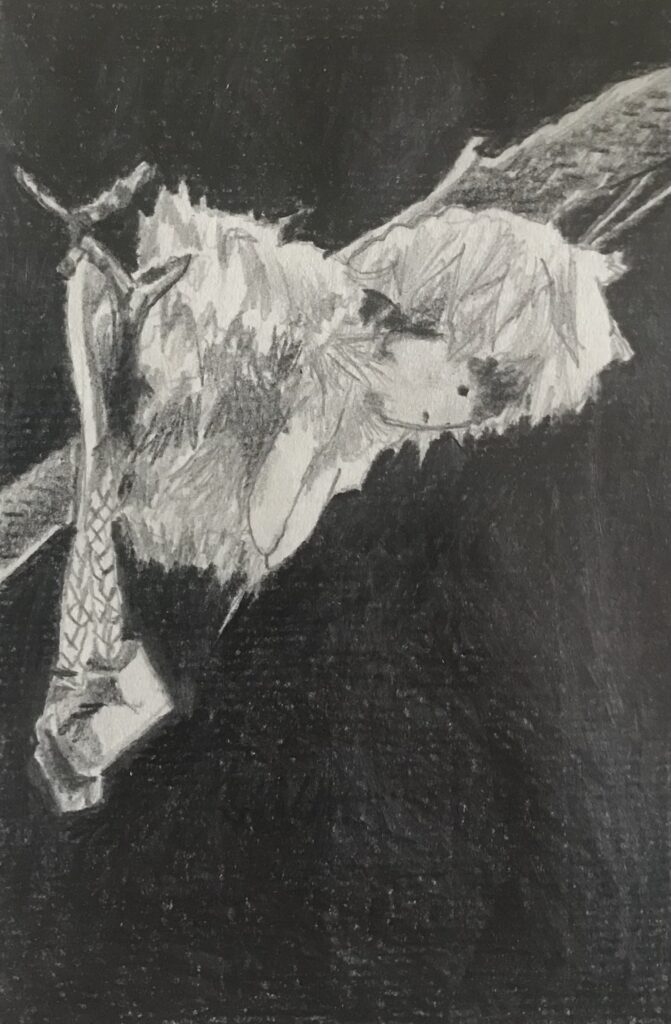

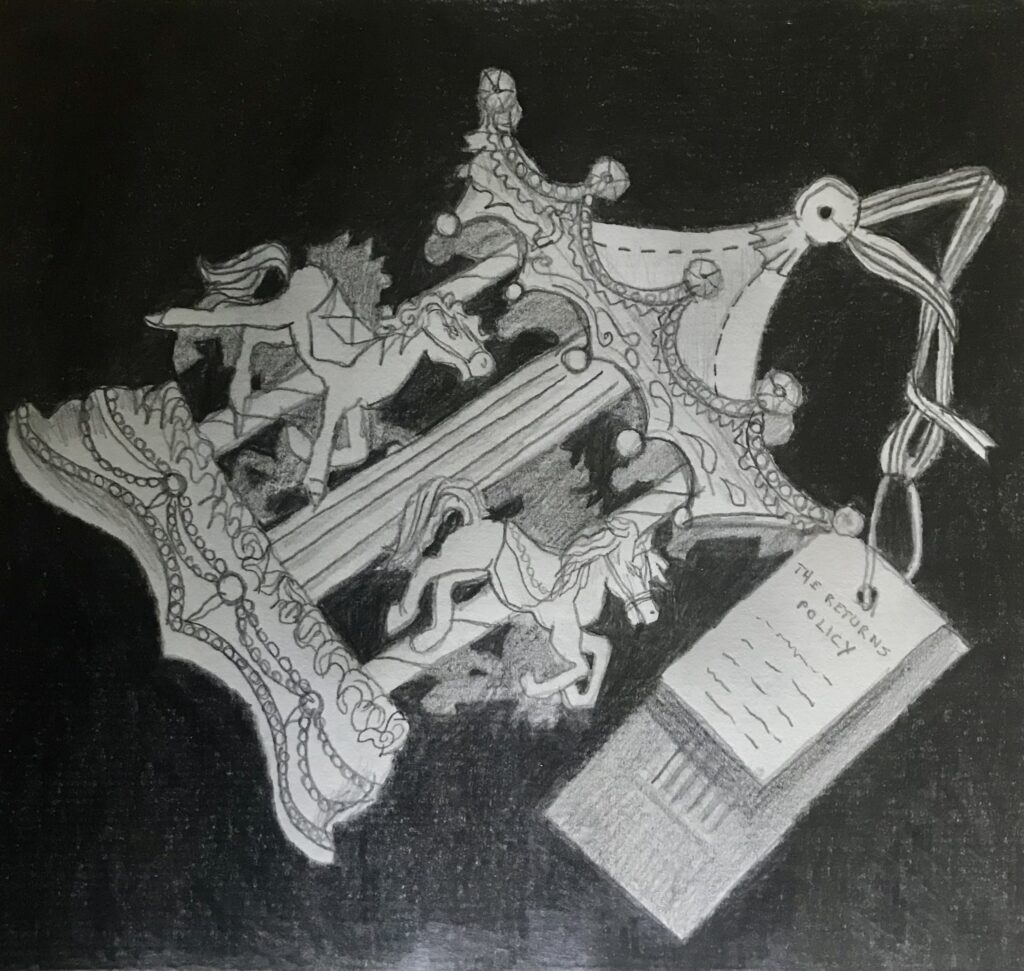

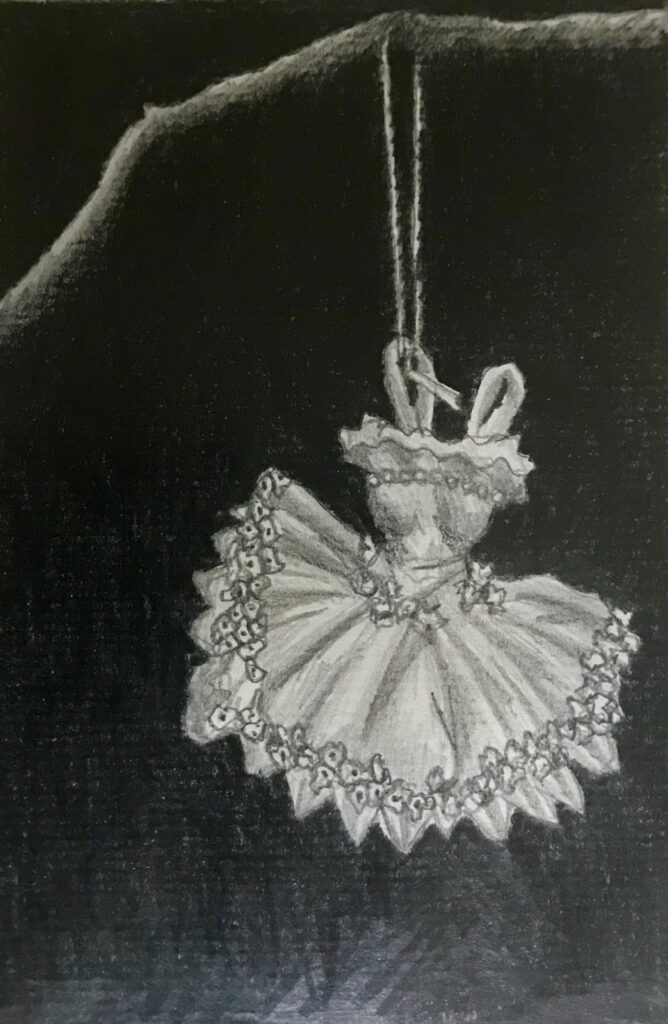

Our second participant returned to the site with her mother and brother, and they hung tributes in the tree together. Whenever she speaks to her mother of visiting the tree, her mother always asks what is left from when they visited last. After her friend died of cancer, our participant commemorated her alongside her brother, as they had shared the same birthday. Her more recent tributes were not ribbons but flowers, in the colours of football teams where appropriate, because they ‘just . . . go back into the earth’. She has also left a five-pointed willow star, and five little brass bells, because five is a number with particular familial significance. The participant’s ritual at The Angel has changed over time, so that she now takes a little picnic and the playlist that she compiled for her friend when she was sick. On each visit, she takes photographs of the tree and shares them with her family and friends, reflecting that it is particularly important to her that those who live so far away know that her loved ones are still important to her. She has pinned the tree in her maps, and she describes it as having many lines of connection that radiate out across the world.

While our first participant saw the tribute as a singular event and our second participant described it as an evolving ritual, for both of them the act of returning to – and photographing – the site was both important and meaningful. The act was seen to be significant in terms of the approval of others – whether of the deceased, or of family members far away. The timing of the return to the memorial was also carefully considered, whether this was in terms of the time of the week or for the commemoration of a birthday.

This section of the sound piece incorporates birdsong from the trees at the memorial site. The field recordings are more lively and vibrant than in the winter months, with the chatter of visitors and the sounds of children playing audible alongside the traffic and the vibrations resonating through The Angel.