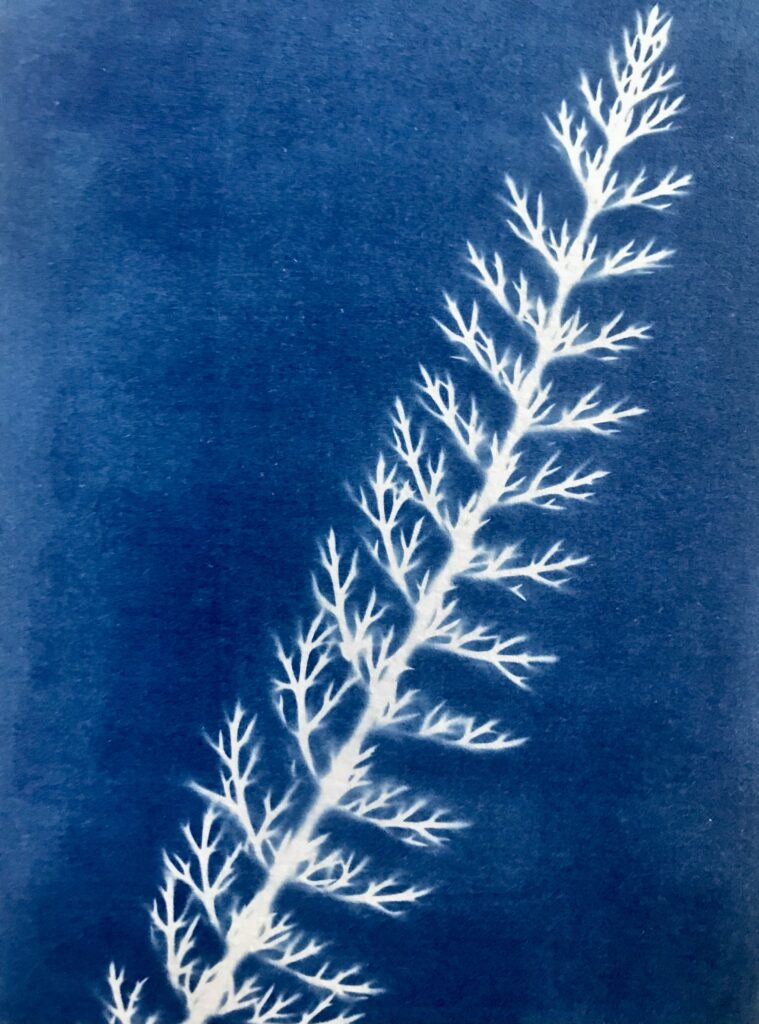

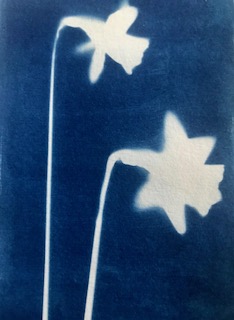

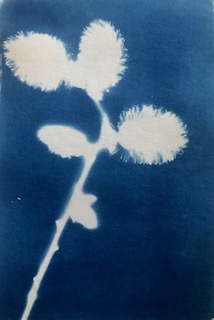

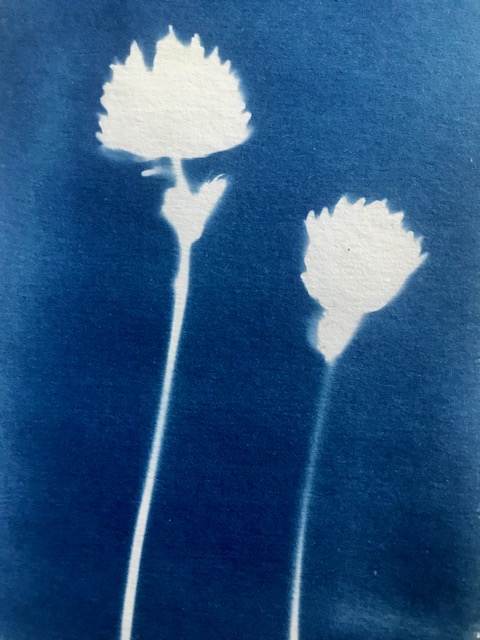

This post forms part of a monthly series that documents the plants growing at The Angel of the North through a series of cyanotypes.

The new month has brought the flowering of the various springtime plants that grow on common land such as fields, parks, and roadside verges – the daisy, the dandelion, and the clover. Their familiar flowers spread across the field on which The Angel stands, reminding us of the everyday nature of this site as post-industrial brownfield land. In this post, I am interested in dwelling on the ordinariness of these flowers, not as an opening onto the history of the site, which I have explored in previous posts, but rather as a prompt for reflection on the grassroots memorial at The Angel as it relates to the ordinary.

If we turn to an influential essay on the grassroots memorial, we can see that the connection between this kind of site and the ordinary is a surprising one. Peter Jan Margry and Cristina Sanchez-Carretero have marked the origin of the grassroots memorial in the 1980s, indicating that it has now become a ‘recurrent pattern’ in the wake of ‘a traumatic event or crisis’ (p. 1). Placing mementoes and tributes at the site of a traumatic event or death becomes a form of ‘social action’ that at once mourns an unexpected death and seeks to effect change, to ‘precipitate new actions in the social or political sphere’ (p. 2). Roadside memorials, for example, both mark the site of a fatality and seek to prevent future accidents by warning other drivers and agitating for the stretch of road to be made safer. The placing of objects removes the site from the everyday, elevating ‘ordinary, secular ground into the extraordinary’ (p. 21). Nevertheless, the authors point out, the primary function of the grassroots memorial is not ‘to create relations with the supernatural’, but rather ‘to manage emotions and to deal with grievances and contestation’ (p. 24).

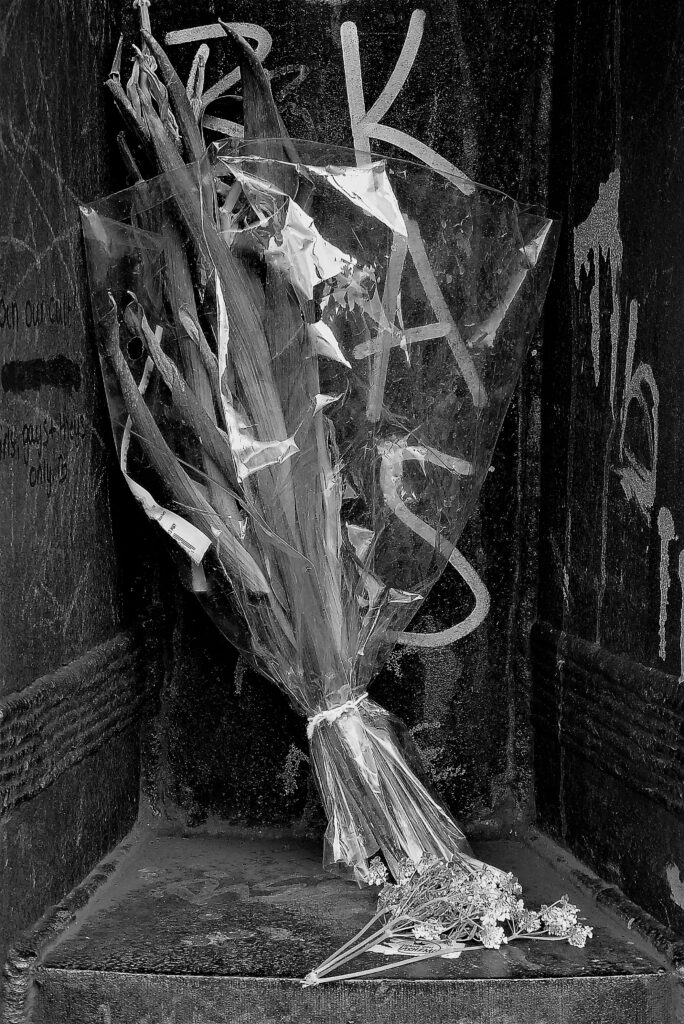

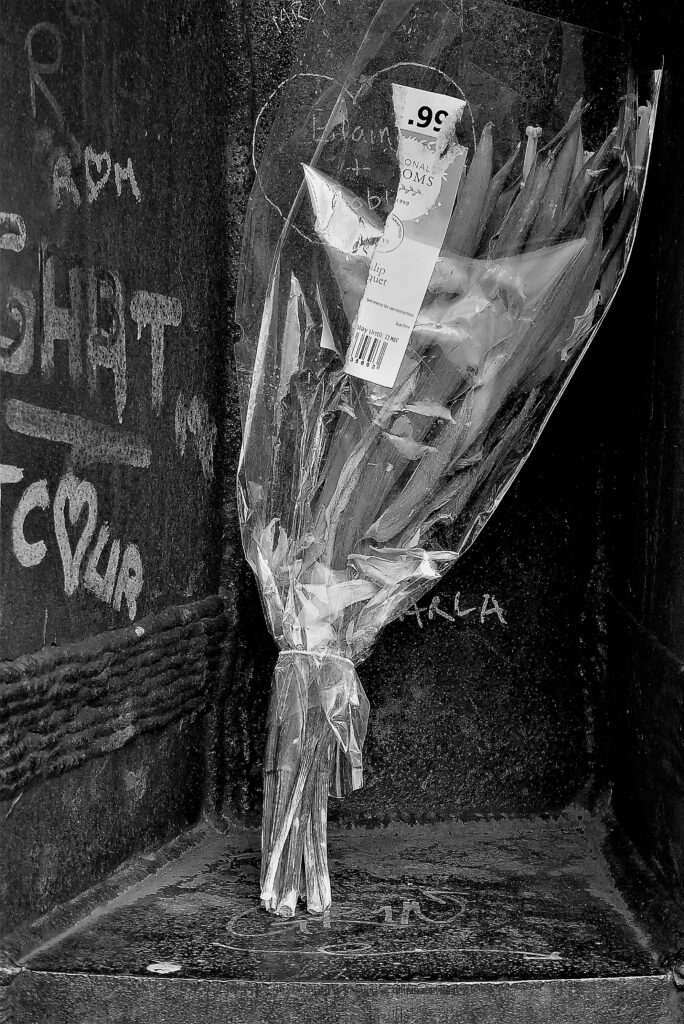

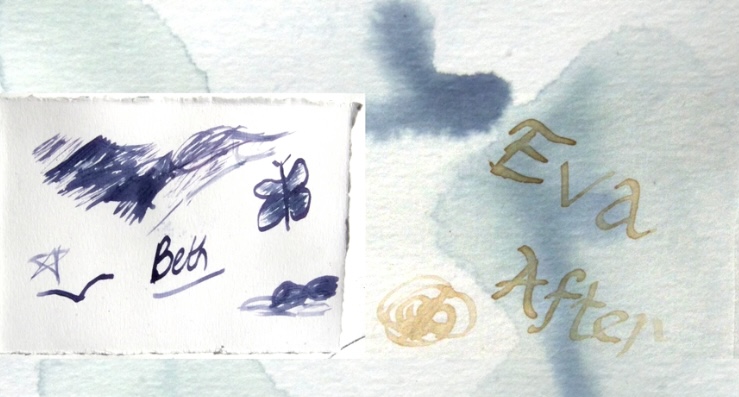

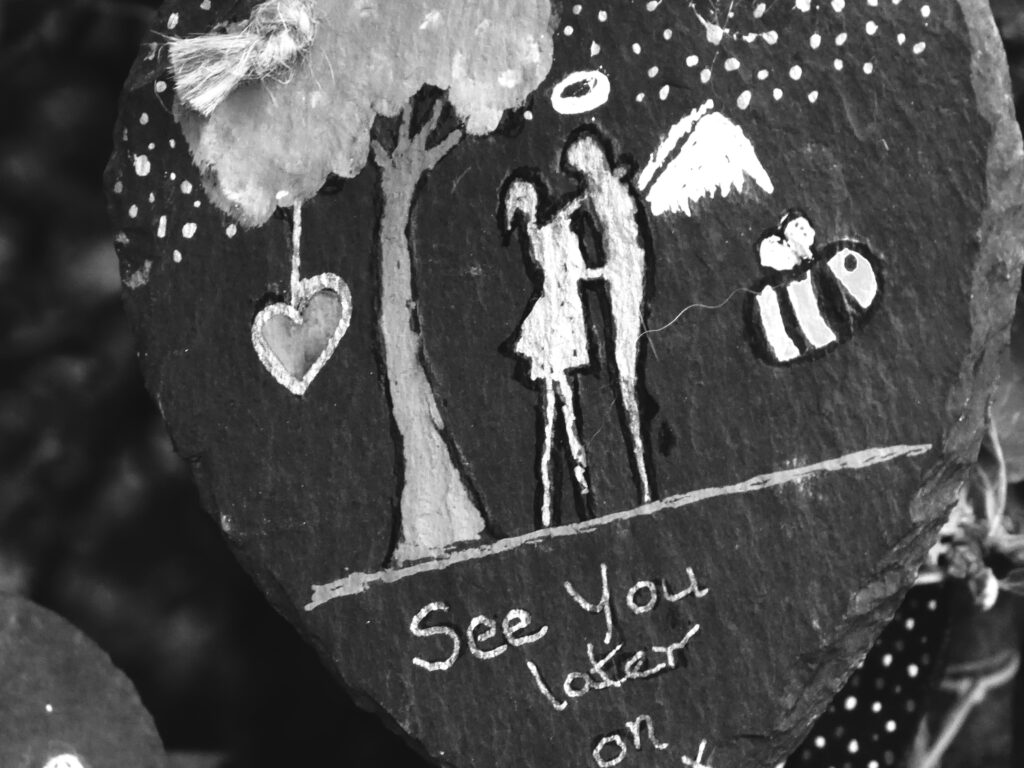

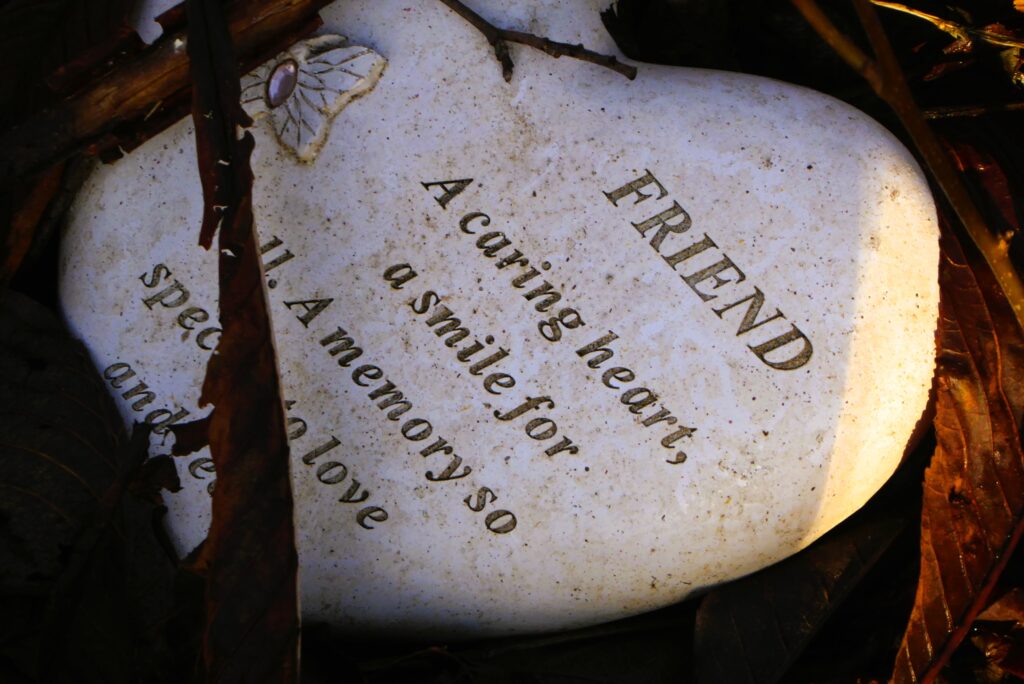

I have pointed out in previous posts that, while the grassroots memorial at The Angel shares in common with other sites the placing of tributes in a public space in order to grieve, it is distinct in that The Angel is not the site of a traumatic event or death, but a place of comfort, and perhaps hope. The social action that Margry and Sanchez-Carretero see as central to the grassroots memorial is largely lacking at The Angel, though traceable perhaps in the possible origins of the site in a grassroots baby loss initiative. I have suggested that there may be something in the memorial at The Angel that enhances or magnifies the sculpture’s effect in transforming the ordinary ground of the field into an extraordinary place, imbued with the feeling of the sacred. But, for at least some of those who leave tributes there, the reasons are more prosaic. The Angel was particularly loved by the person who died. The ubiquity of The Angel in the media offers a sense of permanent contact with the person who has been commemorated there. There is no grave and The Angel offers a place to visit on birthdays and anniversaries. The constant presence of visitors and the memorial tributes left by others offers a sense of companionship for the dead. These are all important and understandable motivations for leaving mementoes at The Angel, but they are expressive less of grievance and social action than of the everyday practicalities of grief.

The ordinariness of the memorial at The Angel does not render it less important than those grassroots memorials that mark the site of a traumatic death, and the love expressed in the tributes is just as strongly felt. By commemorating their losses at the public site of The Angel, there may be, for some, a desire to make their grief visible to others. But this does not seem to be the primary motivation for many, and the evolution of the memorial into individual trees marked out as family ‘plots’ suggests that, with grief rituals in flux, The Angel represents an alternative to the traditional cemetery and increasingly echoes its conventions. The site offers somewhere to visit either if there is no grave – as many friends and relatives return to a place where ashes have been scattered – or if the grave of a loved one cannot easily be reached.

On my visits to The Angel, I have repeatedly witnessed visitors encountering the memorial that they had not expected to find there. Time and again, they stand quietly reading the messages that have been left and looking at the tributes. Some take photographs, but many simply observe. Often, they are visibly moved by an object or a token, or perhaps by the accumulation of tributes that they encounter. One or two have written notes and left them in the trees, recording their own responses to the site. These visitors are not responding to a social agitation that seeks to bring about change, but rather to the everyday, ordinary expression of love and grief.

References

Peter Jan Margry and Cristina Sanchez-Carretero, ‘Introduction: Rethinking Memorialisation: The Concept of Grassroots Memorials’, in Peter Jan Margry and Cristina Sanchez-Carretero (eds.), Grassroots Memorials: The Politics of Memorializing Traumatic Death (Oxford and New York: Berghahn, 2011), pp. 1-48.