In a previous post, I have written about the inclusion of Where We Will Go in the ‘Communities and Change’ exhibition, hosted by Newcastle Contemporary Art as part of the 2023 Memory Studies Association conference. The Memory Studies journal has recently published a special issue related to the conference and, in one of the articles, organisers Catherine Gilbert and Alison Atkinson-Phillips reflect on the various works that were displayed in the exhibition.

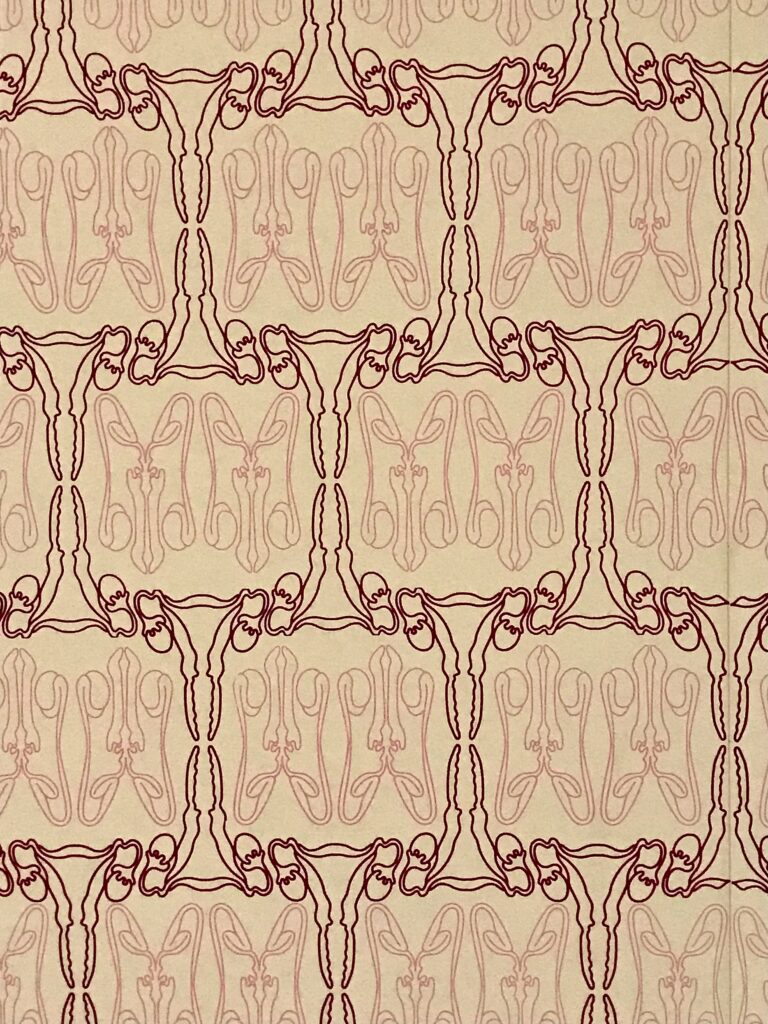

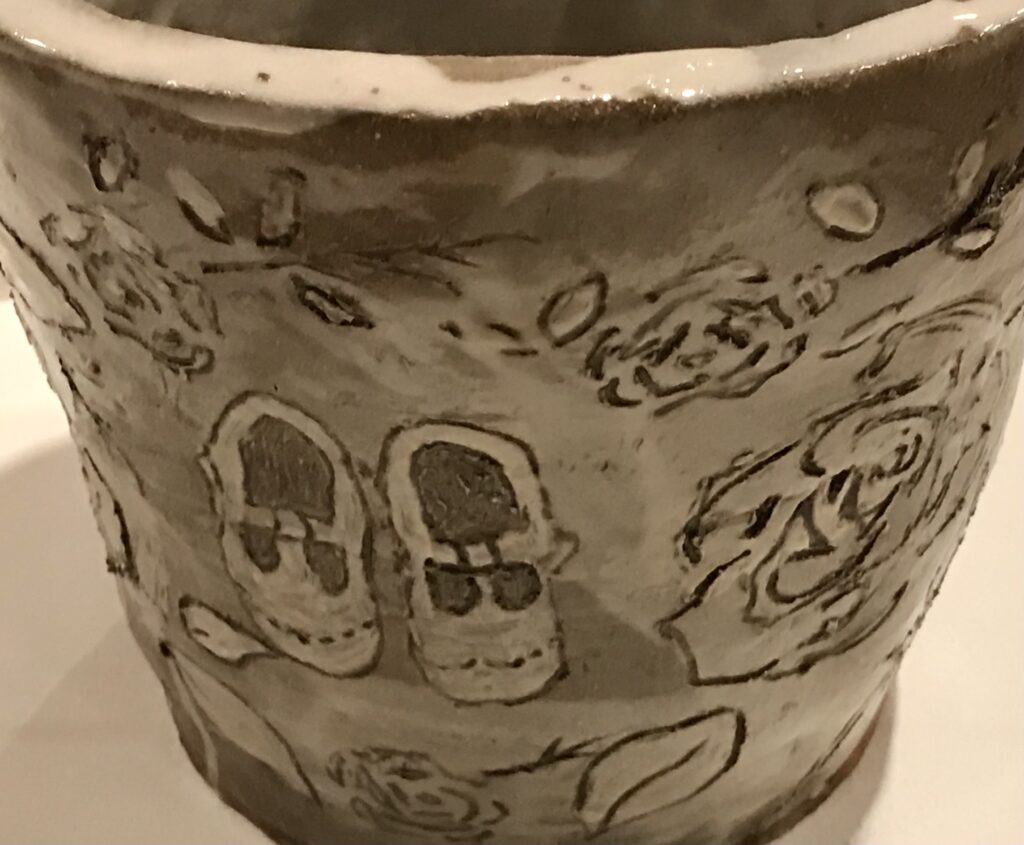

Catherine and Alison note that, in curating the exhibition, there was a strong desire to embed the conference in place and to connect with local communities. They observe the particular poignancy attached to the inclusion of the Amber Collective in the exhibition, because the Side Gallery – their permanent exhibition space in Newcastle – had recently closed due to a lack of funds. Special screenings of two Amber films documented the long history of industrial loss on Tyneside and its impact on local communities. The short film from our project was connected to place through the activity of walking, and it was positioned in the gallery to be in conversation with Henna Asikainen’s ecological installation Delicate Shuttle. Asikainen had walked with people who had experienced migration and displacement, and they had gathered white poplar leaves which were dried and dispersed across a large white wall of the gallery space. Similarly, Kate had invited the parents participating in our project to walk in a place that was meaningful to them, and gather materials that could be used as the basis for the inks. The act of gathering materials and transforming them into another form is a powerful one, and the white poplar leaves reminded me of the rose petals that the parents brought into the workshop, so carefully assembled and preserved. These materials are fragile, even when they have been preserved, and as Catherine and Alison note, they can speak as much of the dispersal of memory as of its conservation in the archive.

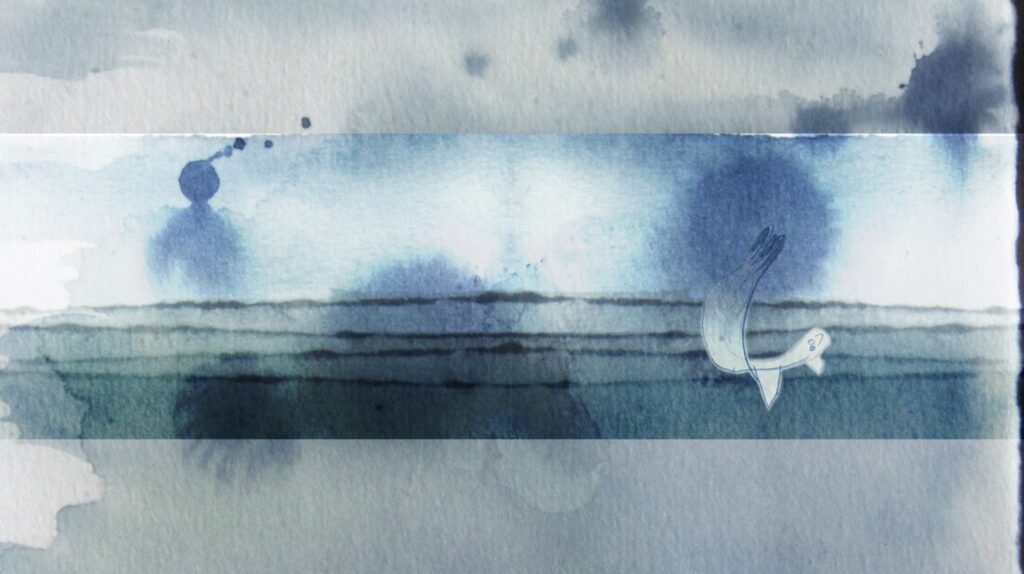

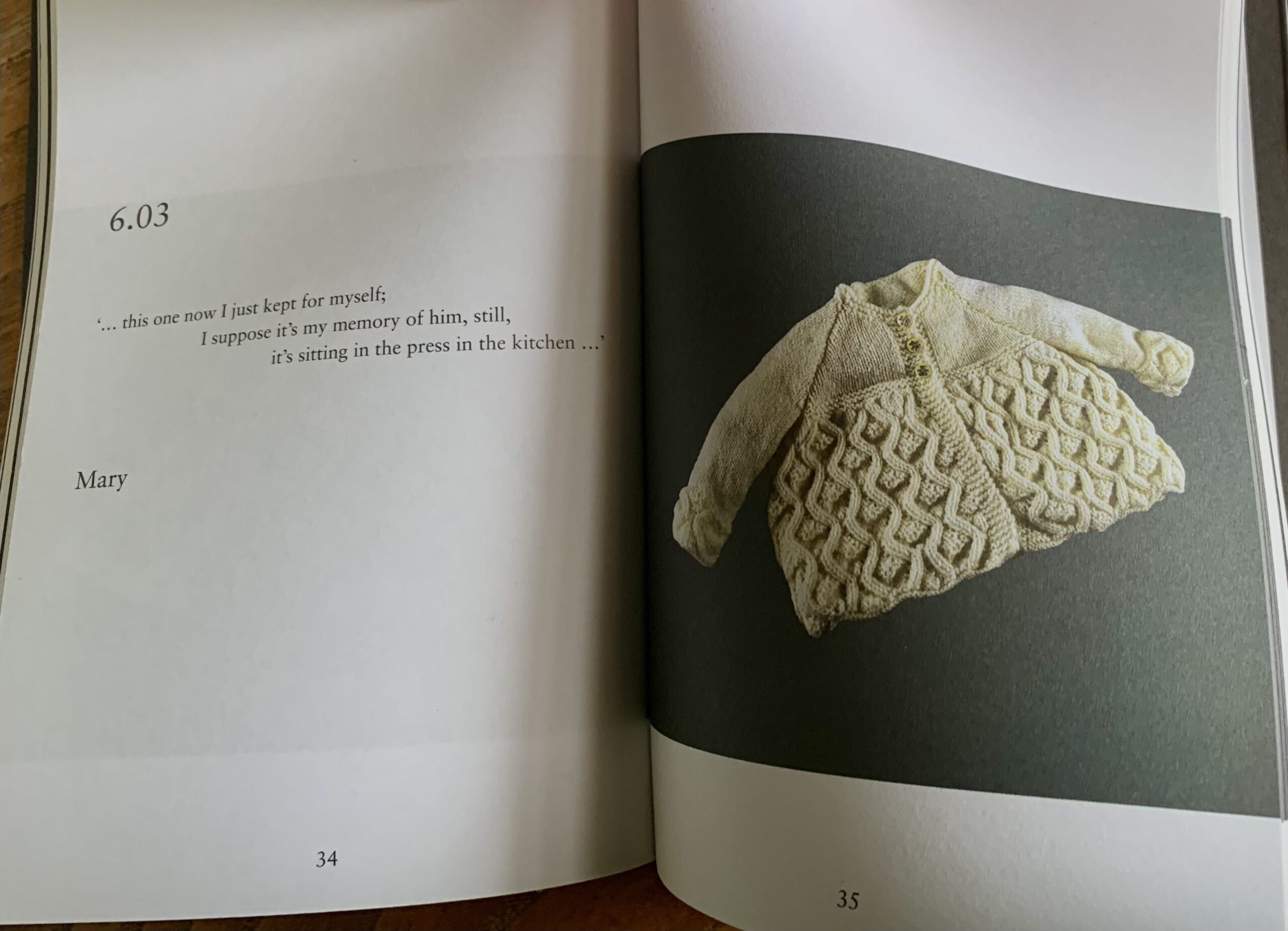

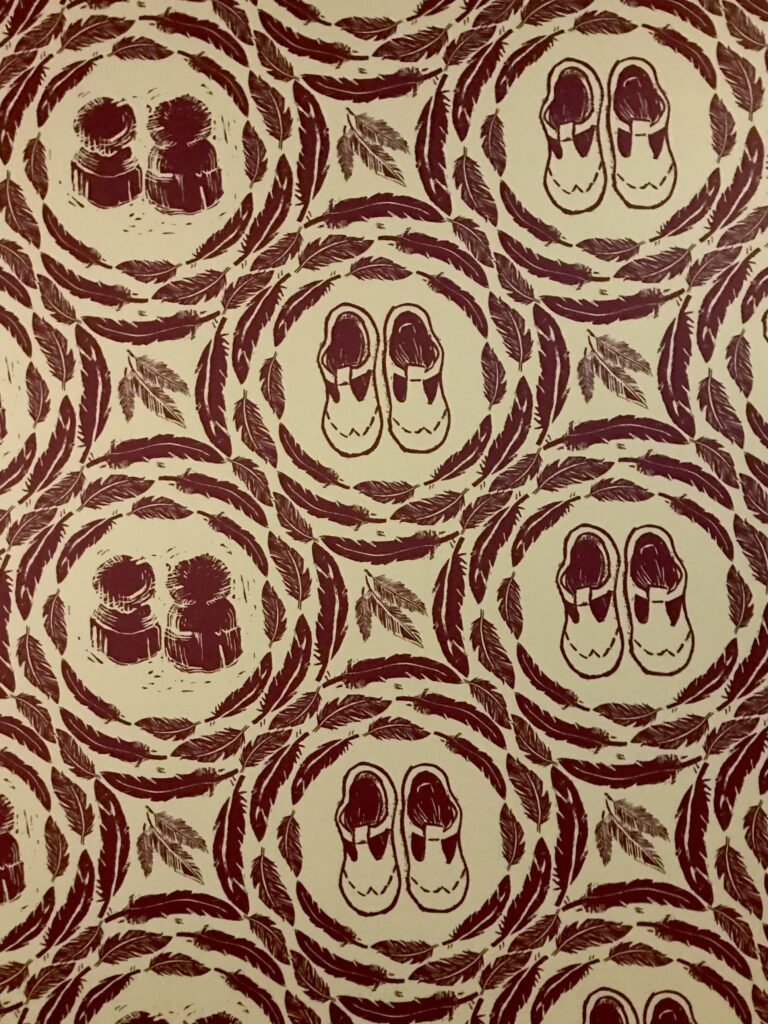

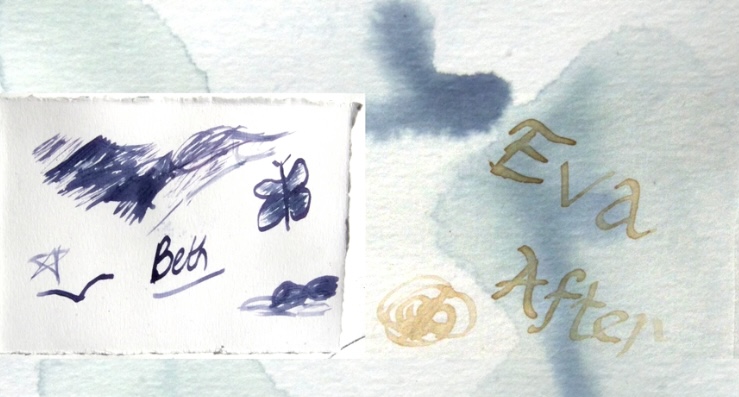

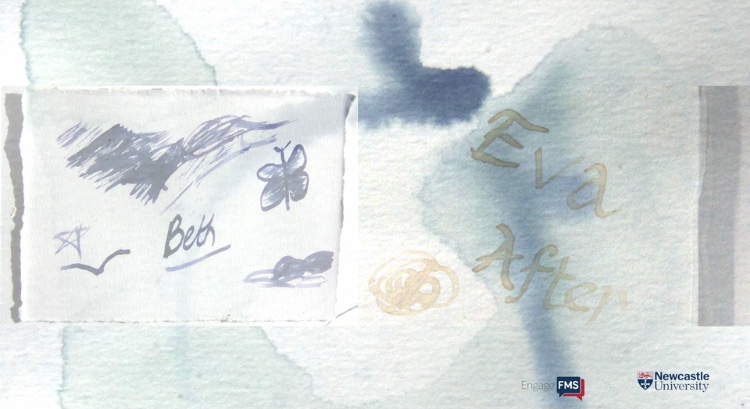

Leaves and petals connect human memories with the more-than-human, reminding us that acts of memory are as much expressions of ecological as cultural community. The question of community was at the heart of the exhibition and many of the installations considered different scales of community. Kate’s film was one of the most intimate communities represented in the exhibition, working as it did at the scale of the family. I have documented in previous posts our encounter, in the course of the project, with the ways in which the loss of a twin at birth resonates across multiple generations of a family as well as rippling out to affect friendship networks. This experience of complex grief is difficult to speak about, and, like the other artworks displayed, Kate’s short film demonstrated that words are not the only way to convey grief. The gathering of materials and making of the inks formed an important act of memorialisation in itself, and the drawings that the parents and the siblings made with the inks provided a further testament to their loss.

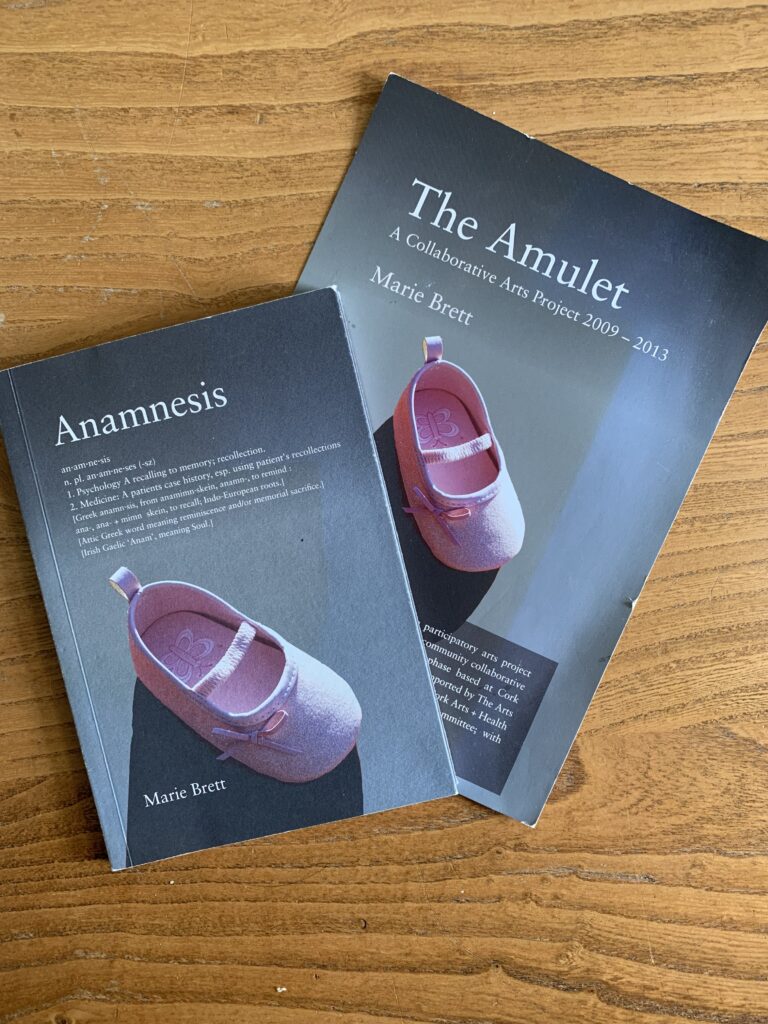

One of the key questions raised by the staging of the exhibition was the place of creative practice within a discipline such as memory studies, which has predominantly focused on the traditional academic outputs of the article and the monograph. Catherine and Alison open their article by reflecting on exactly this question:

The imaginative, and often speculative, approaches afforded by creative inquiry enable creative practitioners to interpret memory in material and embodied ways that are not always easily translated into traditional journal articles. As a community of scholars, it is important that Memory Studies takes this kind of creative-critical inquiry seriously as contributions to the field – not (only) as objects of study from which meanings are extracted and interpreted as a quest to produce knowledge, but as alternative forms of research ‘output’, producing and displaying knowledge on and in its own terms. (p. 354)

These are important questions for the field to address. How can memory studies become more inclusive of creative practice, when it is premised on particular forms and modes of publication and dissemination? What does it mean to value process as well as ‘output’? Which aspects of memory might most effectively be opened up through creative practice? It is becoming more common to see creative exhibitions or performances staged alongside academic conferences and this is a welcome development. At the same time, such creative responses are often not fully integrated into the conference programme, featuring instead as a venue for mingling over lunch or at a wine reception, and/or as a space to visit for reflection between sessions. A final question, then, might be: How could the conference format, as a key expression of the academic community of a field, evolve to become more inclusive of creative practice contributions?

With many thanks to Catherine and Alison for curating the exhibition.

References

Alison Atkinson-Phillips and Catherine Gilbert, ‘Creatively imagining communities: The Communities and Change exhibition’, Memory Studies 18.2 (2025), pp. 354-62. You can access the article here.