‘I’m riddled with appreciation of the ordinary.’ (Richard Farrington)

In Relating Suicide, I wrote about Hunt Cliff, which rises above the former fishing village of Saltburn in North Yorkshire, as a location where suicide is a discernible presence in the landscape. I noted that, in addition to the sign at the peak of the cliff, the National Trust had also erected a suicide-prevention sign at the foot of the cliff, in a bid to reduce the number of suicides at the site. I also reflected on the recent closure of the Teesside steelworks nearby, and the ways in which a lack of employment opportunities and economic deprivation can contribute to a geography of despair. In such a prevailing climate, Middlesbrough had emerged as one of the ‘suicide capitals’ of the UK.

In addition to the official signage at Hunt Cliff, my research for the book had also alerted me to a couple of grassroots suicide-prevention initiatives. Former coastguard, Paul Waugh, had placed hand-painted signs along the cliff edge, with messages written on pieces of slate as warnings of the dangers, and as hopeful reminders that a current state of crisis does not last forever. Inspired by Paul’s example, local schoolgirl Emily Armitage collected stones and painted them with messages and colourful designs. Emily had lost classmates to suicide and accidents on the cliff, and she wanted to do something to help. The UV paint that Emily used to decorate the stones meant that they would be easily seen by anyone walking on the cliff edge. Although I did not include these two examples in the book, they are reminders of the communities of care that arise in relation to suicide, and that, as I discussed, are often represented by local, small-scale actions.

Even though I have often visited Saltburn, I have never walked on Hunt Cliff, and I decided last week to walk along the cliffs to a sculpture by Richard Farrington called ‘The Circle’; an artwork which is also known locally as the ‘Charm Bracelet’. The walk forms part of the Cleveland Way, and is the first part of the stretch that runs south from Saltburn to Staithes. Walking past the Ship Inn, and circling the Old Mortuary, where bodies washed ashore at the base of the cliffs were housed before burial from the late 1800s to 1960, I climbed the set of steps cut into the cliff, noting the suicide-prevention sign at their base. At the top of the steps, a large, carved marker stone offered a welcome rest, and the expansive view looking back along the coast took in Saltburn, Marske, Redcar, and Middlesbrough.

Walking along the cliff, hand-written slate discs were clearly visible from the path, placed carefully at intervals, their messages offering expressions of community and hope, as well as providing the phone number for the Samaritans helpline. Even though there was no sign of Emily’s painted stones, it was heartening to see that Paul’s initiative had lasted, and that the grassroots commitment to suicide prevention was continuing.

Farrington’s sculpture is located midway between Saltburn and the fishing village of Skinningrove. The path follows a disused railway line that originally carried ore from an ironstone mine established at Skinningrove in 1848, which eventually closed in 1958. The sculpture is situated close to the cliff edge, and it was constructed at the British Steel plant in Skinningrove from local materials. The inner section of the circle was made from an old mine shaft mast and the outer part from materials used to reinforce the hulls of trawlers. As well as referencing the industrial heritage of the area, Farrington recycled, in the making of the sculpture, the detritus that the former industrial works had left behind.

I found the sculpture an affecting site. The ‘charms’ of the bracelet each represent a story about local culture, folklore or tradition, and they include a belemnite, a mermaid, a cat, a mermaid’s purse, a bird, a ring, and a horse. Farrington has deliberately not provided details of the traditions or stories to which he refers, which means that the associations of these figures remain loose and speculative. The effect is similar to that of encountering an ancient monument, the significance of which can be intuited, but not fully known. In the strong wind, the ‘charms’ struck one another with an irregular rhythm, so that the circle also became a musical instrument, sounding out strange but oddly comforting notes.

In my book, I described The Stray, the beach where my sister died, as a ‘thin place’. By this, I meant that, for me, the beach is a place where the boundary between the living and the dead feels slight and almost indiscernible, like the sea frets that regularly descend on this stretch of coast in any season. Although there was no sign of mist at Hunt Cliff on the day of my walk, the site of the sculpture evoked the same feeling in me as the nearby sands. It felt as if the sculpture, located on the cliff edge and playing its strange music, was an emanation, or a manifestation, of the site as a ‘thin place’. On approaching the sculpture, I noticed a growing cairn of stones, which indicated that I was not alone in experiencing this sensation. Indeed, Farrington has been pleased by the recent evolution of the sculpture into a secular sacred place: a venue for midsummer gatherings, weddings, and memorials.

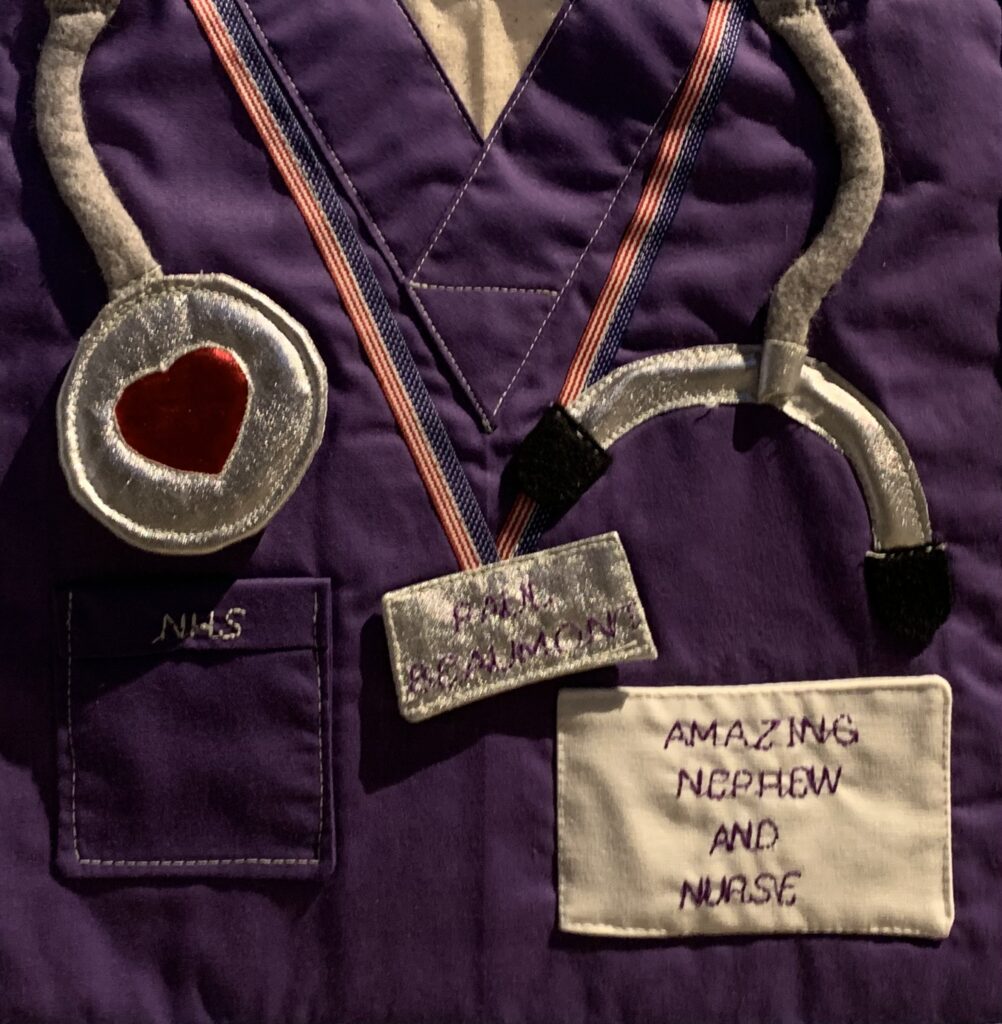

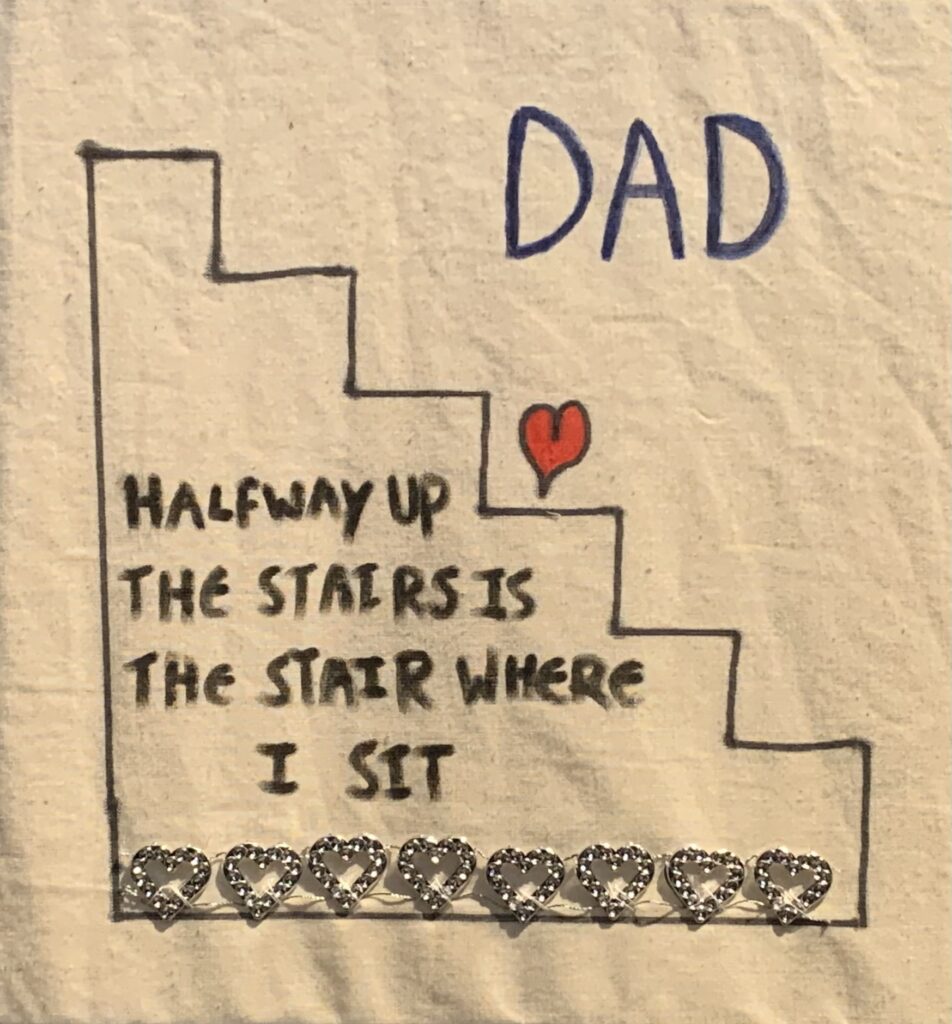

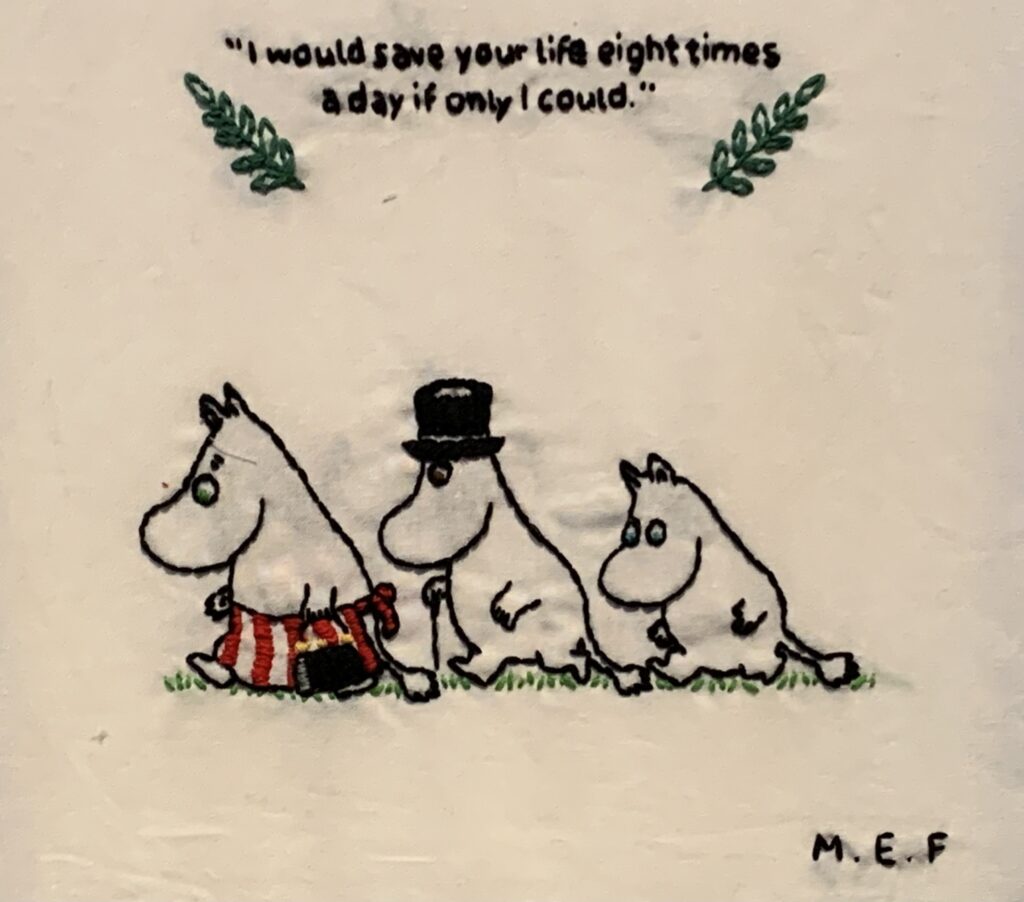

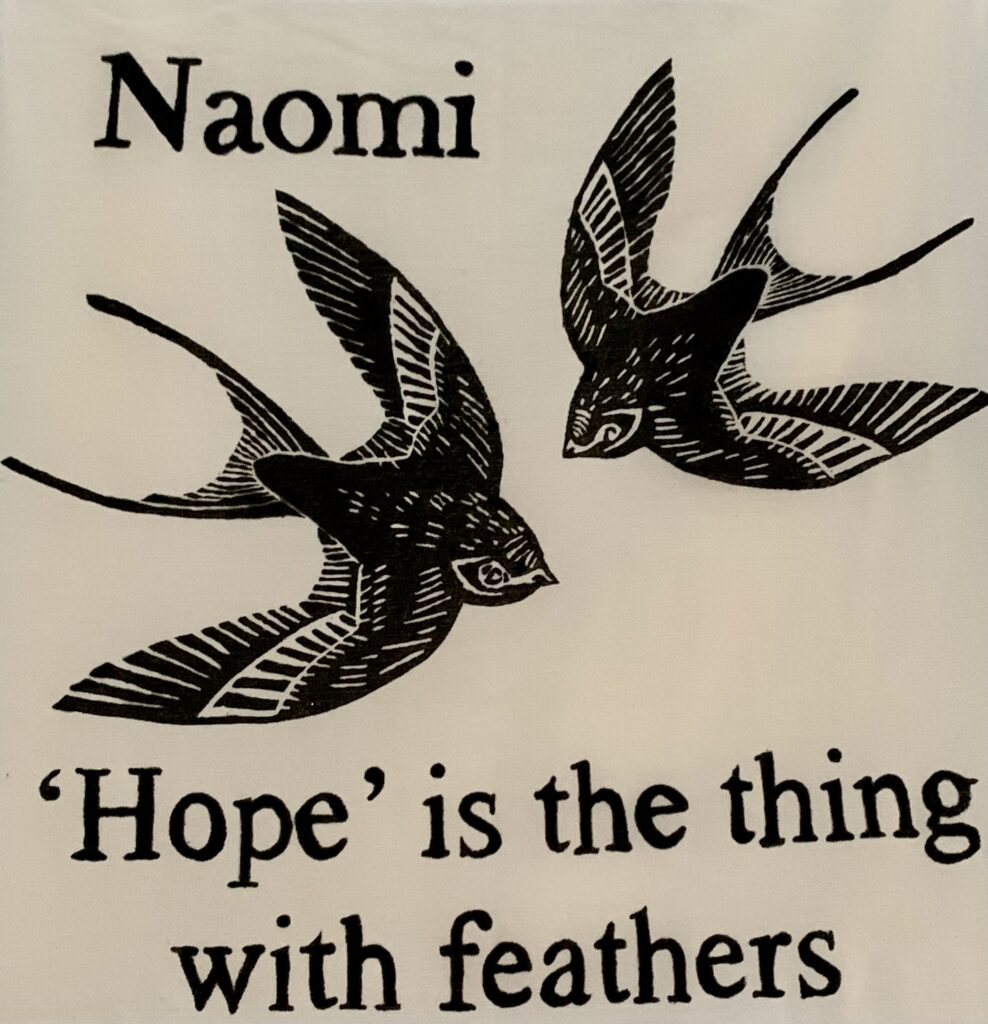

I reflected in my book on hopeful signs that Teesside might be starting to regenerate. These have continued since, with a range of initiatives designed to reinvigorate places that have fallen into dereliction and decay. That said, there are still pockets of deep poverty, and the effects of austerity continue to cast a long shadow across the region. My walk along the cliffs had nevertheless reinforced for me the importance of local communities of care in relation to suicide, and the tangible difference that small, grassroots initiatives can make. Resonating with my Angel of the North memorial project, Farrington’s sculpture also reminded me of the power and potential of public art. At its most effective, public sculpture can act as a prompt or a conduit for feelings that are hard to articulate, and they can provoke echoing responses from visitors in the form of tributes that are left in their vicinity.

Further Reading

Ex-coastguard hopes cliff signs will save lives. – Free Online Library

These colourful stones placed on Huntcliff by Emily could help save lives – Teesside Live