Over the last year, I have been been recording the Angel of the North site by making cyanotypes of the plants that grow there across the seasons. For each month of 2024, I will post photographs of the cyanotypes made in the same month of 2023. Over the course of the year, these images will comprise an archive of the flowers and trees that grow in the field on which The Angel stands, including at the memorial site itself.

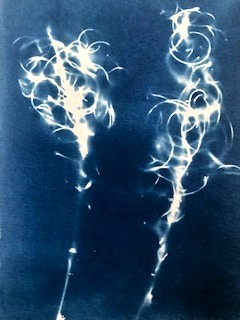

Cyanotype is an early form of photography in which an object is placed on chemically treated paper, laid under glass, and placed in the sun. The sun reacts with the chemicals to expose the image, and the print is developed by rinsing the paper in water, which produces the distinctive deep blue ground. I have used the process of dry cyantoype, which means that the treated paper is dry when the object is placed on it.

Last week, I visited York Art Gallery to see the British Museum touring exhibition Drawing Attention: Emerging Artists in Dialogue. My eye was drawn to the work of Irish artist Miriam de Burca, who makes meticulous drawings of clods of earth dug up from the edges of cillini, burial grounds across Ireland that mark the resting places of those considered unworthy of an ‘official grave’: babies and children who died before they were baptised, women who died in childbirth, and those who ended their own lives. De Burca’s studies are an act of paying close attention to those whom society wished to forget, an assertion of remembrance that challenges a collective amnesia. In the exhibition, de Burca’s drawing was paired with Giovanni Francesco Grimaldi’s Design for a Catafalque (1621-58), which represented a memorial for someone that society wished to honour and esteem. The intricate detail of De Burca’s ink drawing encouraged close and sustained attention to it, and I found myself returning several times to the image as I went round the exhibition.

De Burca’s project is very different to documenting the memorial at The Angel. The burial sites in Ireland are obscure and often remote, situated on the edges of bogs, lakes and seashores, or just outside the walls of graveyards. Lacking any visual markers, the earth that de Burca digs up, draws in her studio, and then returns to the site, is a way of rendering the unseen burial ground visible, and each drawing is titled with the co-ordinates of the site’s location. The memorial at The Angel is not a burial ground, although the ashes of loved ones are sometimes scattered there. The objects that people leave behind give visibility to the memorial, and its location next to The Angel means that it is neither obscure nor hidden. The memorial objects are nevertheless sensitive and personal. Although the cyanotypes do not share the same political purpose of de Burca’s drawings, which deliberately set out to expose and challenge an institutional architecture of disappearance, they hold in common with them a mode of looking at a memorial site that is attentive yet oblique.

January’s cyanotypes capture the sculptural seedheads of the previous summer’s flowers, and they appear as doubly spectral: the negative image of a form that itself represents the ghost of an earlier season. The weak winter sun is also documented in these images – despite long exposure times, they have a more faded blue ground than the cyanotypes that are developed in the summer months.