Last week the Newcastle University Medical Humanities Network hosted Helen Knowles to speak about the Birth Rites Collection. An artist and curator, Knowles built up the Collection, which is the only collection of contemporary artwork dedicated to the subject of childbirth. Founded in 2009 and currently housed at the University of Kent, the Collection was formerly held at King’s College, London.

Knowles spoke about the history of the Collection, which seeks to encourage debate and increase awareness of practices of childbirth. She addressed questions of curation, and of the display of artworks that represent sensitive subject matter. She then presented a virtual tour of the Collection, highlighting and discussing a number of its key works.

The first artwork on the tour concerned the subject of baby loss. Bella Milroy’s Sharing the Gift From Elanor addressed the artist’s relationship with her older sister, who died shortly after birth. The work comprises a photograph taken on the hospital ward just after Elanor’s birth. Beneath this photograph is a reproduction of the same image, made by Milroy nearly thirty years later. The two images ask us to register the differences between them. The photograph captures those who were present to witness Elanor’s brief life, and provokes remembrance for those who were there. The reproduction emphasizes that Milroy’s access to the scene is secondary, and that she can only imagine rather than remember her sister.

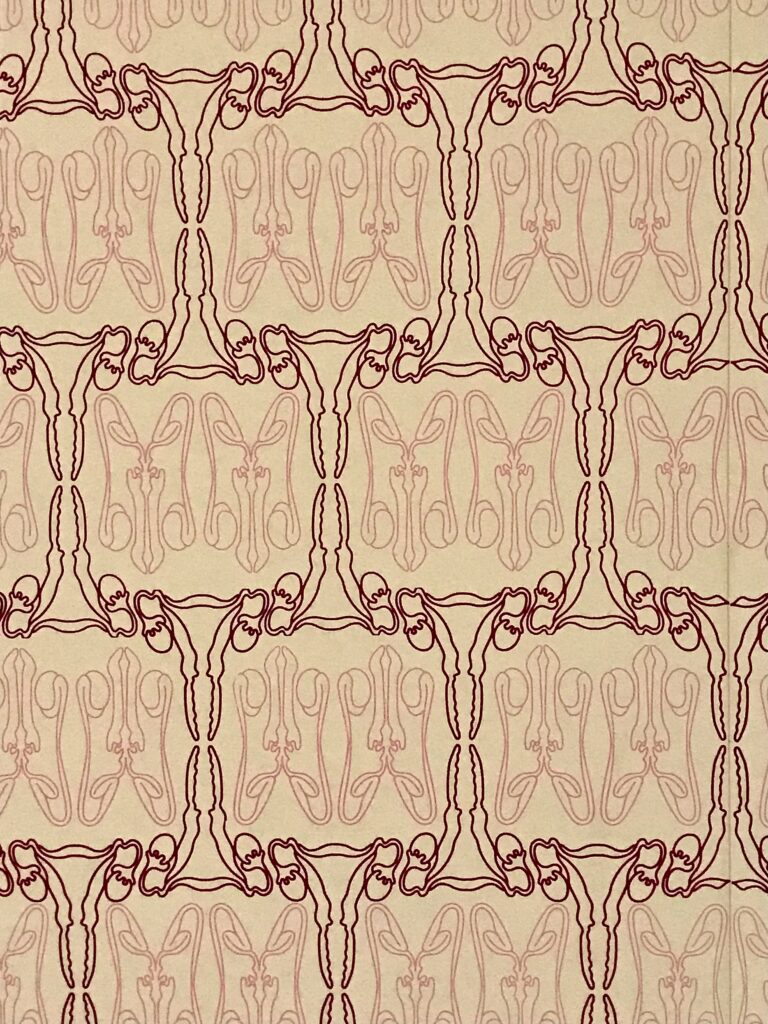

Other pieces in the Collection that address baby loss acted as key reference points for our own project. Knowles’ work is represented in the Collection through the printed wallpaper, Conception. From a distance, the pattern looks like an art-nouveau design, but close up it becomes apparent that it depicts scientific details of the reproductive organs. The wallpaper was on display at the Whitworth Art Gallery’s exhibition Still Parents: Life After Baby Loss, which was showing when we worked on the project, and which both Kate and I visited. Every aspect of the exhibition, from curation to interpretation, had been informed by the project participants; namely, parents who had experienced the loss of a baby during pregnancy or just after birth.

Working with professional artists, the Still Parents project encouraged participants to explore their experiences through creativity. Memory boxes displayed around the walls contained intimate objects that were associated with the loss.

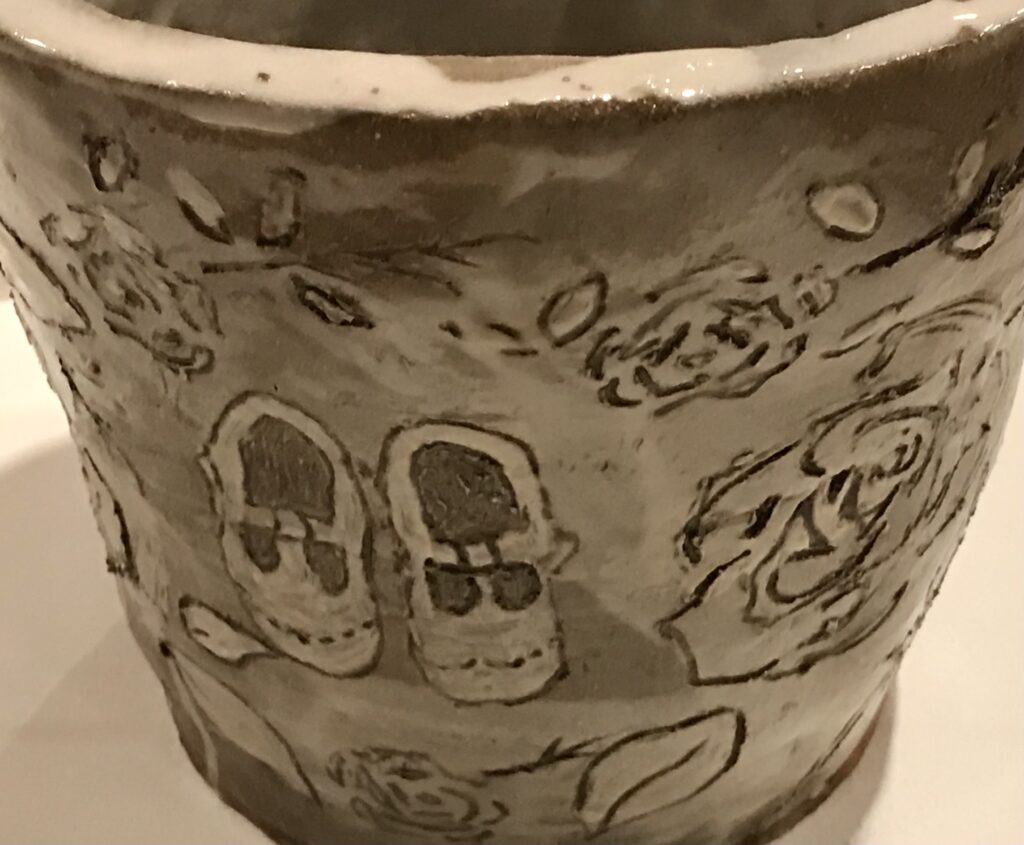

It was moving to see how these objects were transformed across different media. This pair of shoes was worked into clay and fired as decoration on a pot.

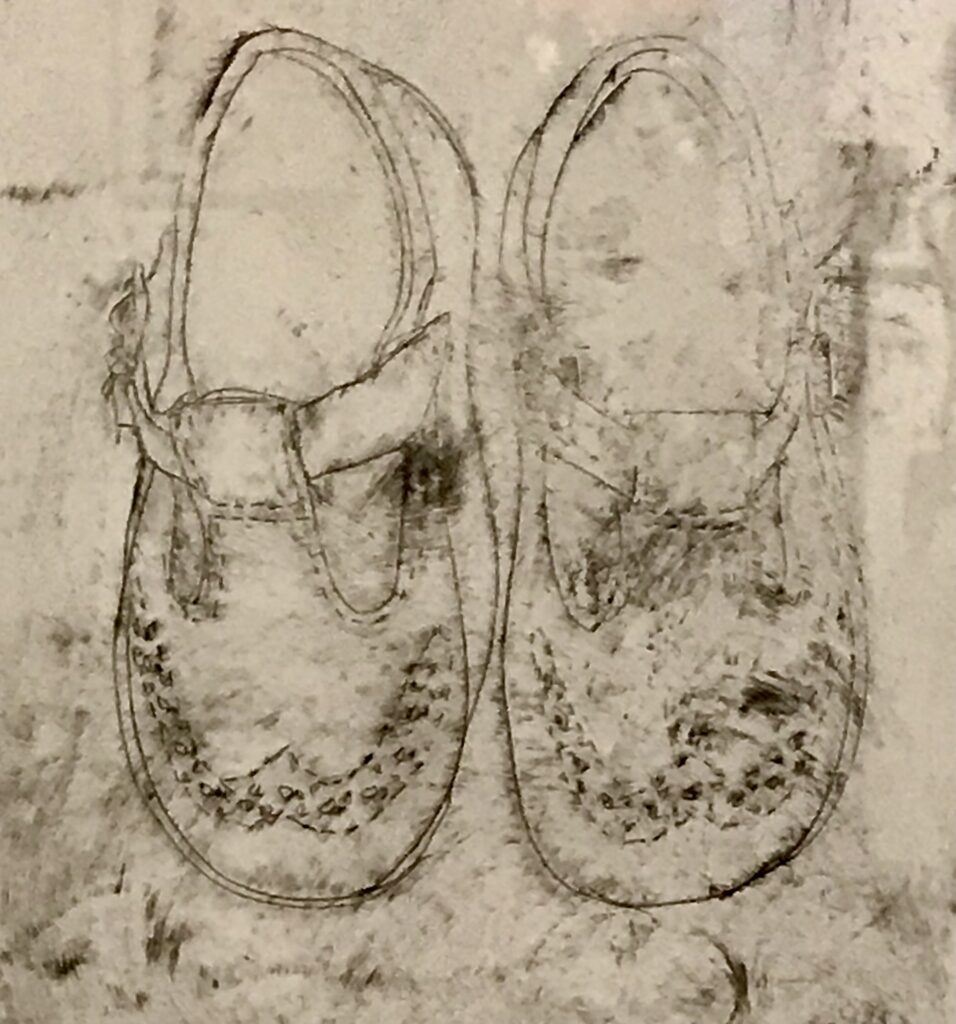

The shoes were etched onto paper.

They were embroidered onto cloth.

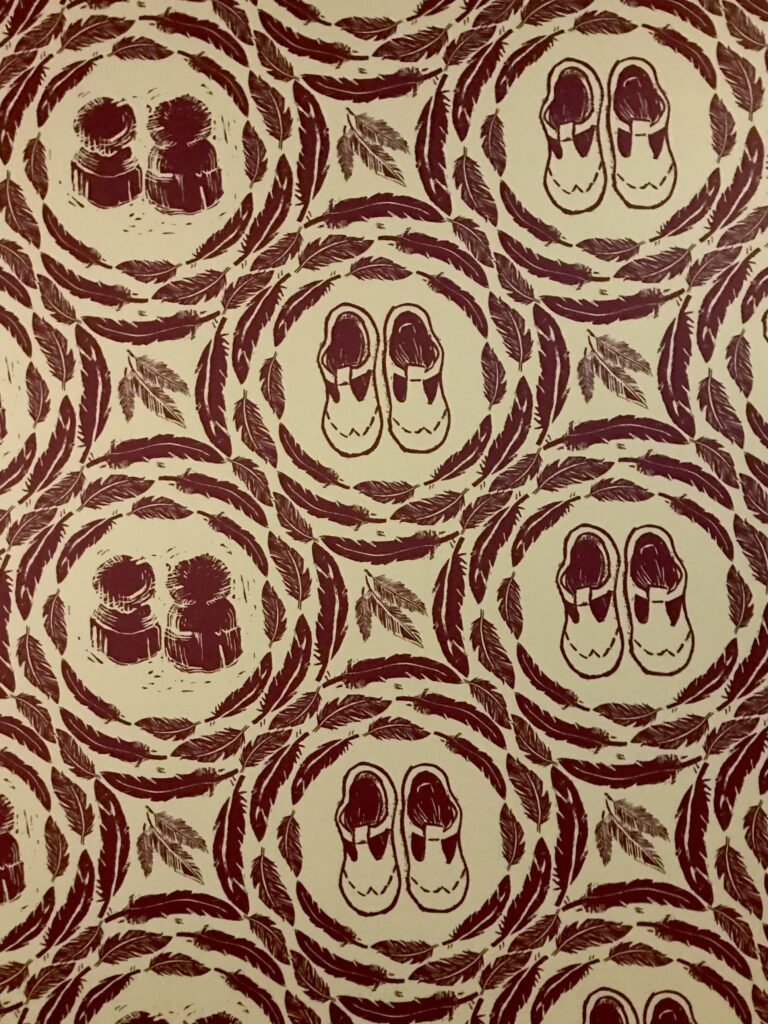

And they became part of a wallpaper pattern, combined with a little woolly hat from a different memory box.

Although our project worked with materials that were more indirectly associated with the loss, the transformation of those materials into ink, drawings, and the digital medium of film was based in the same process of enabling parents to explore their grief through creativity.

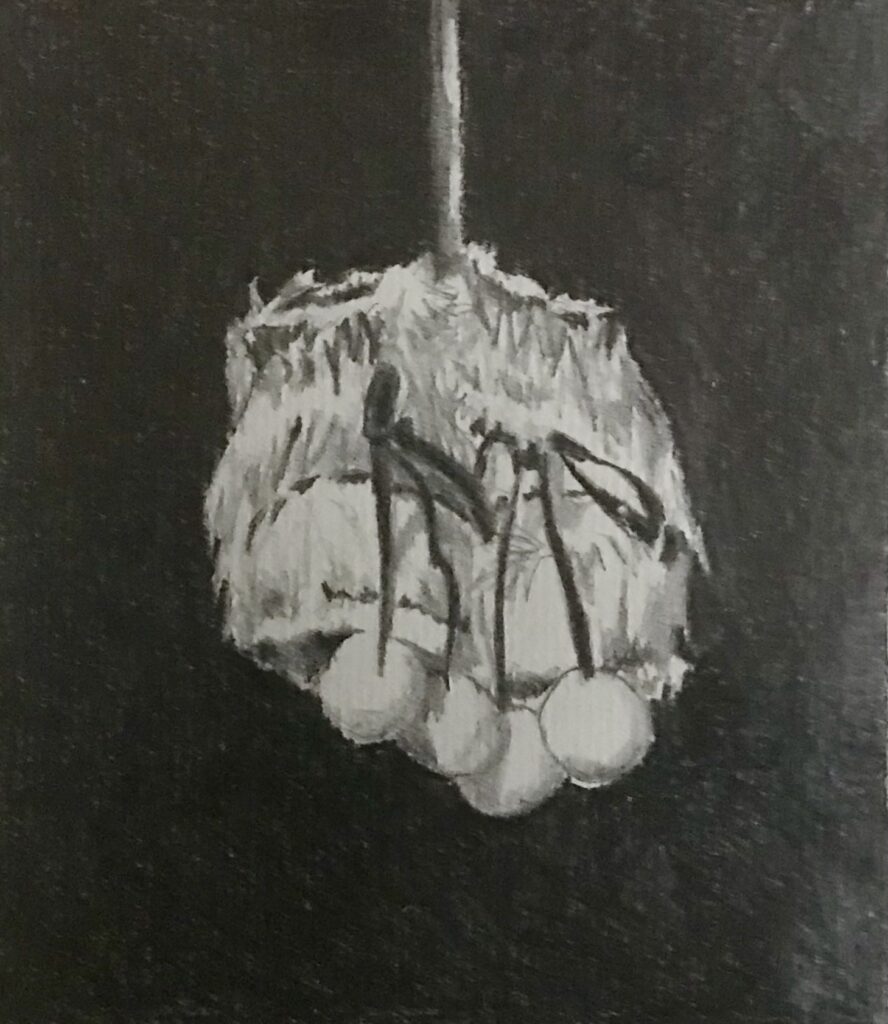

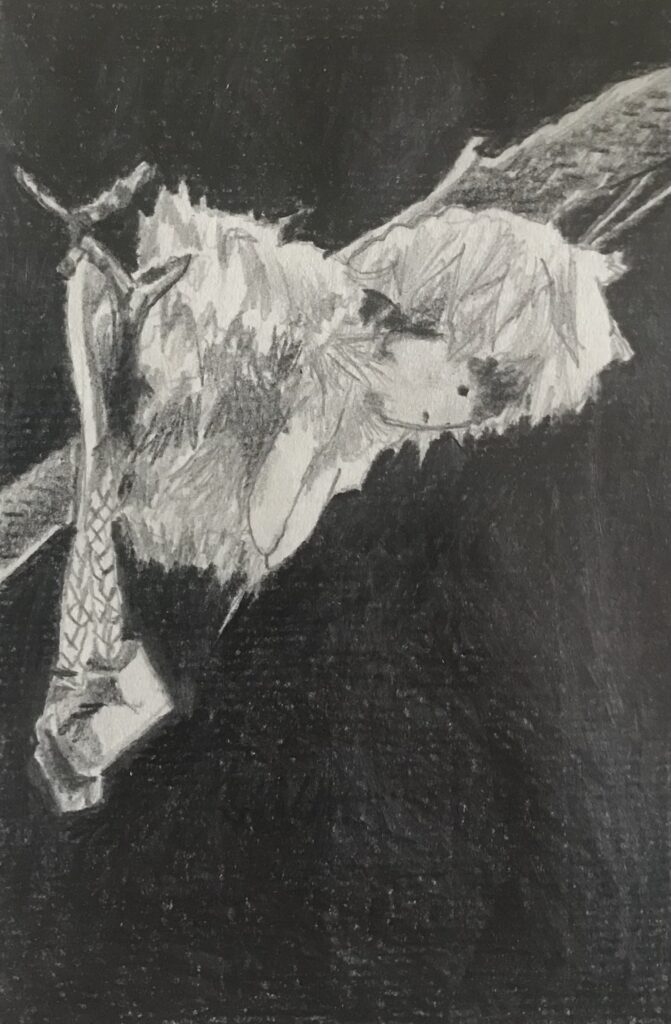

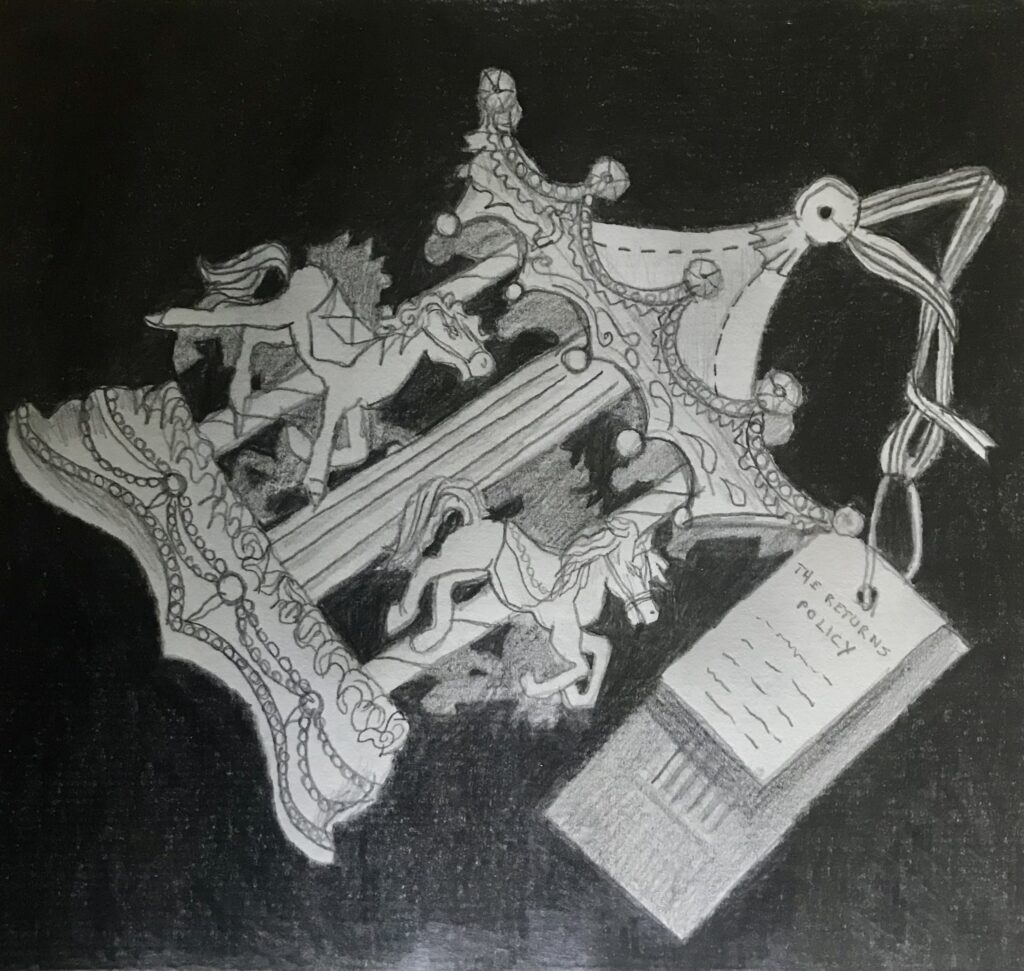

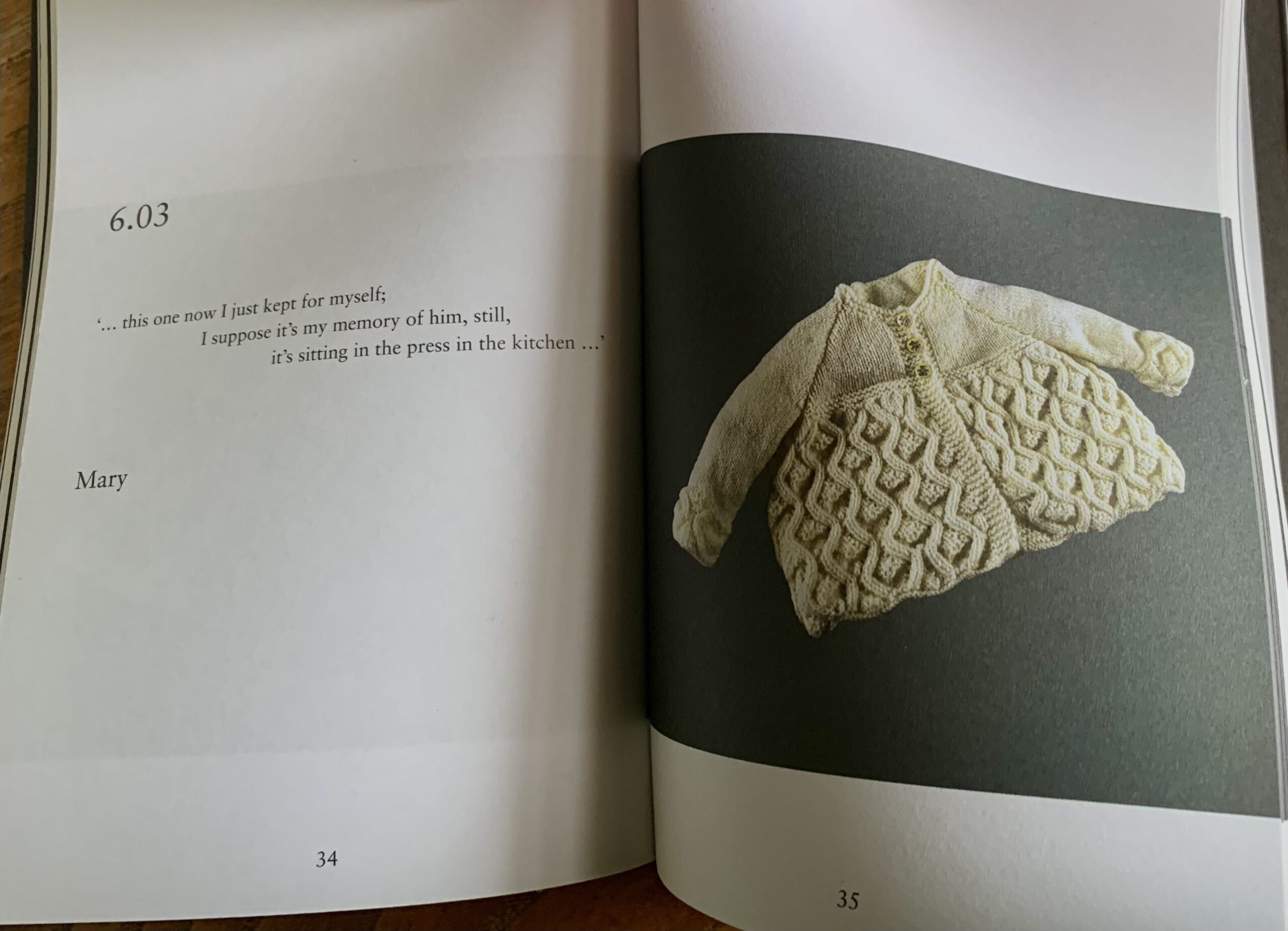

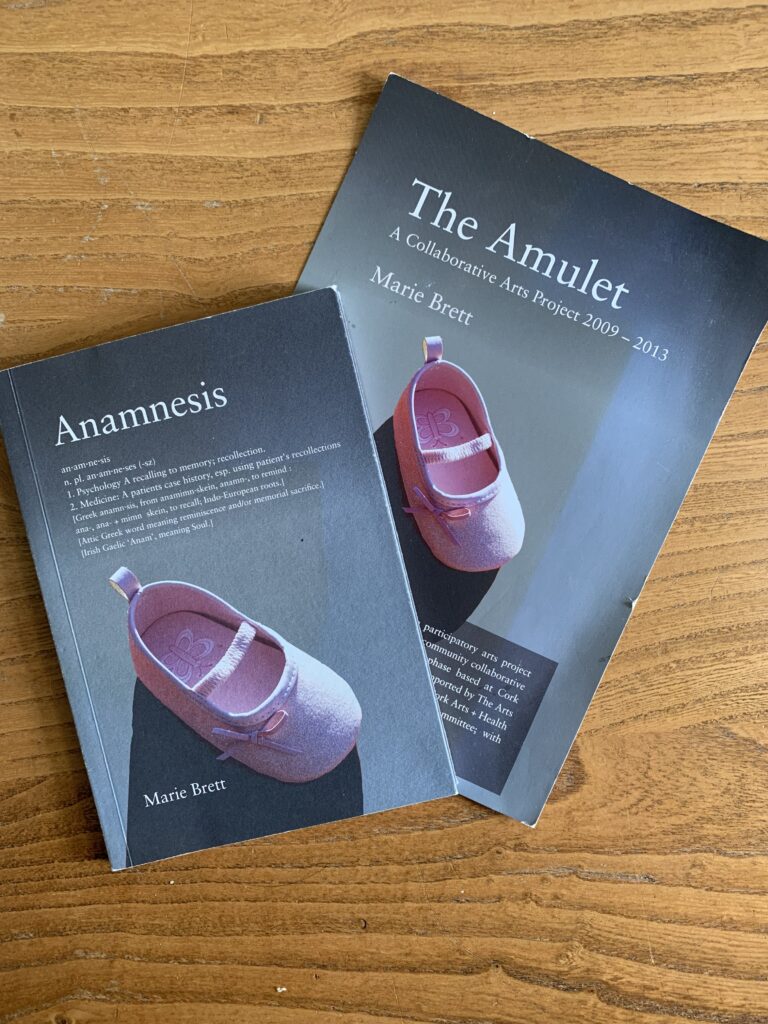

Marie Brett’s Anamnesis: The Amulet also forms part of the Birth Rites Collection. Developed in partnership with three Irish maternity hospitals, Brett’s project explored the amulet as an object that holds particular resonance in the context of pregnancy and infant loss. The exhibition displayed ten photographs of mementoes connected to lost infants, which were matched with audio clips of the parents speaking. The Collection holds the tables on which the photographs were displayed, the framed prints, and the CDs and headphone sets.

The words of the parents were very personal (see the pages from the exhibition catalogue, at the head of this post), yet Brett’s decision to place them in conversation with one another was suggestive of the power of objects in the context of grief. Many of the mementoes were kept in a safe space at home and brought out for private rituals of remembrance. In the Irish context, the public display of images of these objects challenged long-standing cultural taboos about infant death. I have written in previous posts about the cillini, clandestine burial sites across Ireland where babies’ bodies were buried in secrecy, often at night. The project’s sharing of stories offers parents the opportunities to talk about their children, and opens up a public conversation around their denied memories.

As I type these words, I have on the desk in front of me the publicity flyer and catalogue for Brett’s exhibition, which were given to me by Judith Rankin when we first discussed collaborating on our project. Although we were not working in the cultural context of Ireland, the experience of losing a twin at birth still remains largely silent in the broader conversation around pregnancy and infant loss.

It was wonderful to learn from Helen about the Birth Rites Collection, as well as to encounter both new and familiar artworks that chimed with our project on baby loss.

Many thanks to Olivia Turner for organizing the workshop, and to the Newcastle University Institutes of Humanities and Arts Practice for supporting the event.