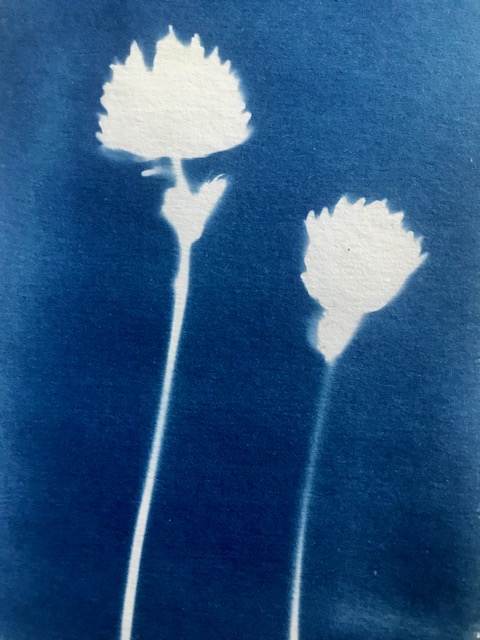

This post forms part of a monthly series that documents the plants growing at The Angel of the North through a series of cyanotypes.

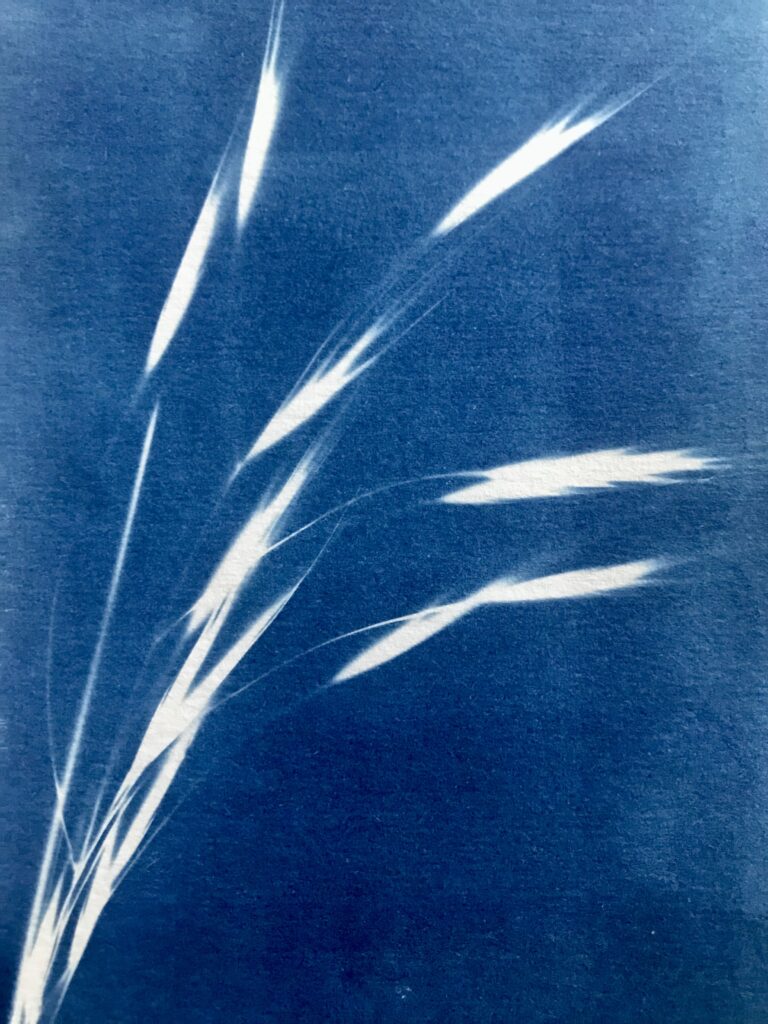

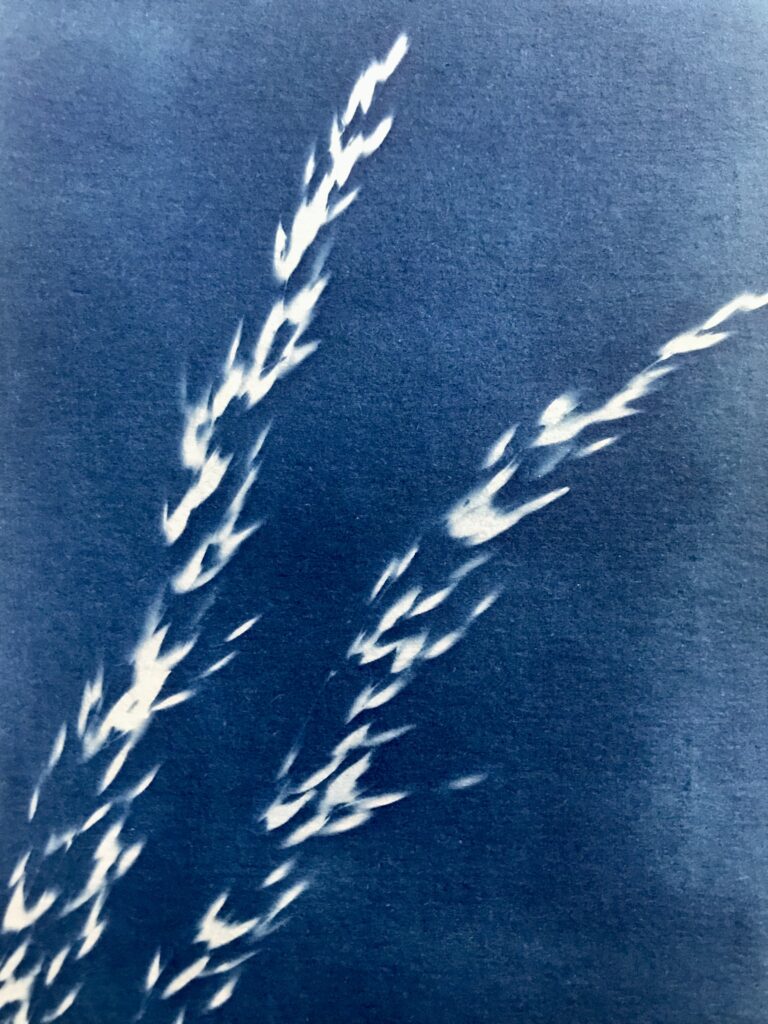

The month of June has brought into flower the different grasses that grow in the field on which The Angel of the North stands. Attending to these plants requires a different scale of vision from looking at The Angel, as well as adjusting the gaze downward. Cyanotypes of the grasses bring out the sculptural beauty of their forms, which are easily overlooked.

I wrote in my post on the month of May about the significance for the memorial site of dwelling with the ordinariness of things, and this month’s homage to the grasses that grow there continues in this vein. These plants are not exceptional or extraordinary, but looking at them closely reveals their distinctive beauty. I have often used the term grassroots memorial to describe the memorial in the trees at The Angel. This phrase, which registers that the memorial site is rooted in the spontaneous, collective activities of ordinary people, has its origin in the roots of grasses as a fundamental layer from which growth takes place.

The Sounding the Angel project documents the memorial site through sound. I have written in this blog of the rustling of the leaves in the trees as one of the defining sounds of the memorial site in the summer months. Although less audible, the whispering of the grasses can also be heard alongside them, as they variously bend or shake in the wind.

The images of the grasses above have all been made using the dry cyanotype method, which involves placing the plant onto paper when the chemicals that develop the image have dried. The grace and elegance of these cyanotypes prompted me also to develop images of the grasses using the wet cyanotype method, which I have described in a previous post.

This technique enables a greater range of effects, even if it is less predictable in outcome.

This image captures the feel of the grasses swaying in the wind, and turmeric sprinkled onto the wet paper enhances its sense of life and movement.

Here, the textured background has been created by placing a layer of cling film onto the glass during the exposure of the image.

Here’s another variation, which combines the two techniques. The pooling of vinegar spray on the cling film has caused a rich variety of blues to emerge.

The cyanotype methods differ in their effects, but they both capture the structural beauty of the grasses. These plants define the site of The Angel in June, and this post both captures and celebrates the range of different species that grow there.