This post forms part of a monthly series that documents the plants growing at The Angel of the North through a series of cyanotypes.

In my posts for January and February, I observed that the plants growing at The Angel site were largely the sculptural grasses and seed heads from last year’s flowers. The site is exposed to the high winds of the winter storms and these plants have bent and bowed as successive storms have passed through. Low to the ground, they are less vulnerable to damage than the trees of the copse that forms the main memorial site. Some of the branches of the outer trees of the copse have blown down, and the memorial tributes hanging from them have been scattered by the winds across the ground nearby.

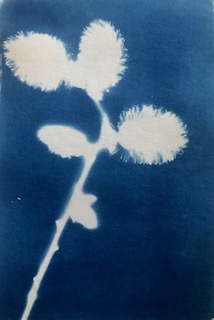

In the field surrounding The Angel, catkins are forming on the trees: an unmistakable sign that the season is turning. This Spring is warm but wet and the ground is muddy underfoot, especially on the path that runs through the trees. Visitors to The Angel linger to look at the tributes at the entrance to the copse, but do not often venture further in.

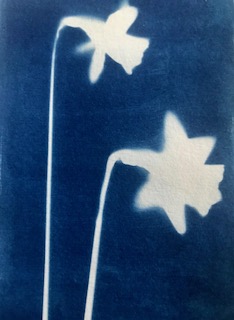

Those visitors who do walk through the copse are rewarded by the sight of clumps of daffodils growing under the trees. These are a cultivated variety of miniature daffodils and their location beneath the trees amid the memorial tributes suggests that they have been planted in a memorial capacity. Their yellow blooms glow against the muddy paths and represent a sign of hope in the aftermath of recent storms.

Visitors regularly leave floral tributes in the trees, tying them to the trunks with the florists’ wrapping still around them or placing them on the ground next to other memorial objects. Flowers will also sometimes be left at the feet of The Angel. This form of tribute echoes the act of leaving flowers at a grave, or the tying of flowers to benches or railings at other grassroots memorial sites. Sometimes the flowers at The Angel are accompanied by messages, while other tributes are left anonymously.

The daffodils planted in the trees at The Angel represent a different kind of gesture. Their annual flowering suggests that The Angel is seen as a more lasting or permanent memorial site that could be visited over a number of years. The flowers, interspersed in clumps throughout the trees and clustered at the centre of the copse, do not belong to any one person but speak, instead, of an anonymity-amid-the-collective that characterises many of the tributes left at the site.

The flowering of the daffodils speaks to the ephemerality of many of the tributes left at The Angel. Every time I visit the memorial it is different: objects have been laid down or removed, or sometimes they have changed position within the site. As this monthly series of cyanotype blog posts documents, the site also changes with the seasons. In March, the daffodils are briefly visible in the trees and become a prominent feature of the memorial site, although they would pass unnoticed at any other time of the year. In asking what The Angel represents for those who leave memorial tributes there, it is therefore also important to consider when it is being visited. The area in the trees feels very different according to the season, and even to the time of day. Documenting such a site accordingly necessitates a slow methodology that consists of repeated visits over an extended period of time. Only then is it possible to capture the ephemeral and fleeting aspects of the site, alongside its more stable and permanent features.