I have written in previous posts about finding a pile of stones at the entrance to the trees at The Angel of the North and being unsure about whether they constituted a memorial tribute or not. I have also written about my own act of weaving thread around a stone picked up from the beach on Holy Island in Northumberland, and questioned whether I will return the stone to the beach. In this post, I reflect further on the tributes that are left in the trees at The Angel that take the form of stones.

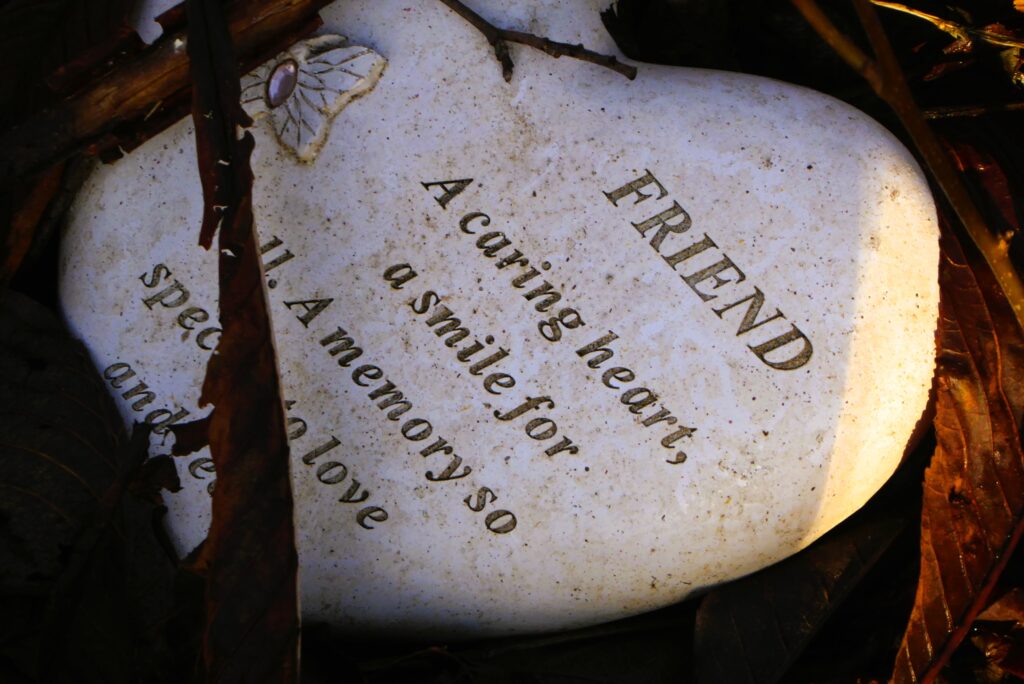

Placing stones or pebbles as tributes is a common contemporary memorial practice. It is an act that is democratic and open to all, and it is not bound to any specific faith. At the same time, it has a long tradition in a variety of faith contexts, for example the placing of a stone when visiting a grave in the Jewish religion, or the accumulation of stones into a cairn in acts of Christian pilgrimage. In both examples, leaving stones represents an act of witness. In contemporary tributes, stones can be ritually brought from a particular place or they can be more spontaneously picked up and left as a token of remembrance, sometimes in response to visiting a memorial site. Stones might be unmarked, representing the memory of someone known only to the visitor, or they can be inscribed with messages and images in a memorial practice that is readily accessible to everyone, including children.

The act of leaving stones at The Angel is one memorial practice amongst others and, whilst these tributes form part of a collective vernacular practice at the site, they are left as individual acts of remembrance rather than being placed together to form a memorial pile or cairn. The stones will often be inscribed or painted and are placed at the foot of a tree beside other commemorative tributes, either to the same person or to different individuals. The stone will typically be painted or inscribed with pictures or the name of the person who is being remembered, and/or significant dates. In the photograph above, the visitor has inscribed a name and dates, but these have faded so that they are no longer legible, while the four painted butterflies that flutter across the stone remain visible and express a more personal meaning and significance.

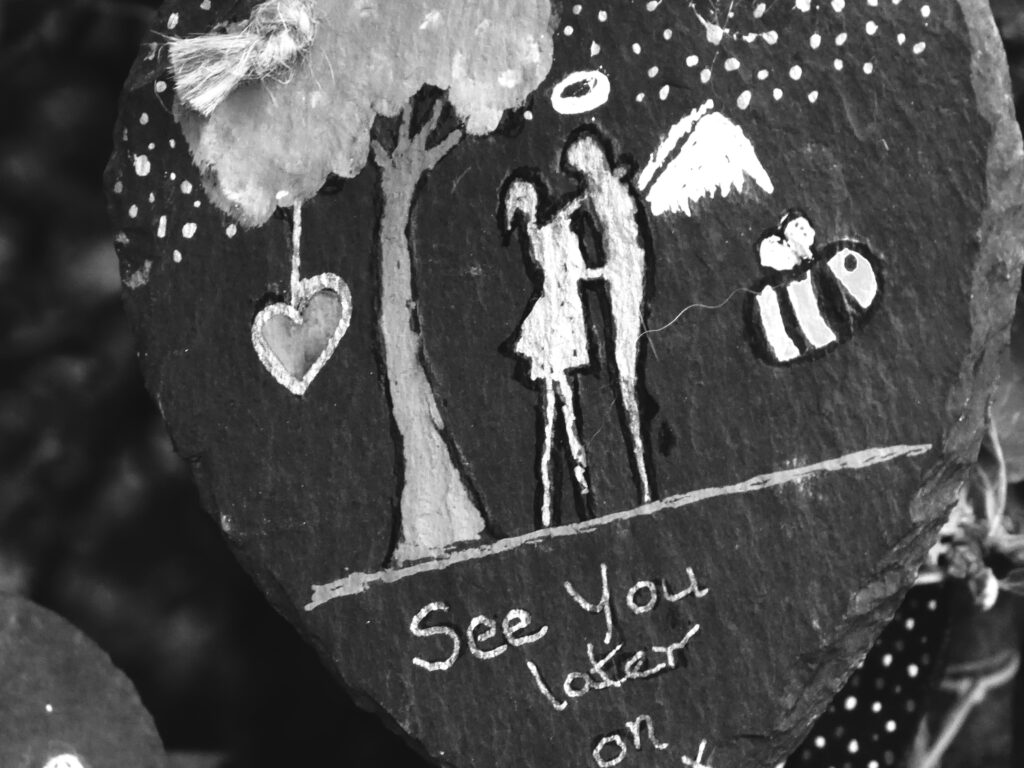

More recent tributes left at the site have taken the form of paintings on slate plaques that are suspended from the branches of the trees. The slate is cut into the shape of a heart or other memorial tribute, and is personalised by painting images or words on its surface. The slate tributes that have been left at The Angel take the form of messages addressed to the deceased, and speak of the visitor’s continuing bond with them. Memorial slate plaques often appear in cemeteries and at graves as well as in more spontaneous or grassroots memorial sites such as The Angel. They can be left in remembrance of parents, children, siblings, grandparents, partners, friends or pets.

Some of the tributes at The Angel have been carved or incised with a message that speaks of the person’s relationship with the deceased and expresses their feelings about them. These memorials are planned rather than spontaneous offerings, and the messages have more permanence than the painted pictures and words. Again, these tributes are also left at more traditional memorial sites as well as at grassroots or spontaneous memorials.

Some of the stones left at The Angel are unmarked and represent a private act of witness and remembrance. Their placing in the trees and beside other tributes identifies them as commemorative objects. These might be individual stones or pebbles, or they might be placed as a group, either to commemorate different members of a family or as tributes to a single person from a few visitors. One poignant tribute at The Angel took the form of a heart-shaped stone broken into two, with other pebbles arranged around and between the halves, expressive that grief has the power to shatter even such a durable material as stone.

Stones can form part of a commemorative ensemble, significant not only in themselves but also in their relation to other objects. An area of stones can demarcate the boundaries of a commemorative ‘plot’ beneath a tree onto which tributes are placed, echoing the spatial arrangements of a cemetery. This formalisation of the memorial site at The Angel has been increasingly visible as it has evolved over time. Stones can also be used as a prop or support for other objects, such as the tiny figure of an angel that has been placed on a painted stone amongst other tributes at the base of an alder tree in the copse.

In an article on the stones placed at the Witness Cairn on the Isle of Whithorn in Galloway, Scotland, Avril Maddrell has described these tributes as ‘individualised micro-memorials’ (p. 675). Maddrell is interested in the ways in which such acts of commemoration blur the boundaries between bereavement practices and expressions of belief manifest in particular places, suggesting a continuum of belief-unbelief in contemporary Britain. This complex intersection of grief and belief has relevance to The Angel site, and I have indicated that some of the stone tributes are continuous with more conventional and faith-based sites and practices of grief.

I also find Maddrell’s term of’ individualised micro memorial’ suggestive in the context of The Angel site for its registration of questions of scale. Gormley designed The Angel of the North as what we might term a collective macro memorial, both in the sense of its size and dominance in the landscape, and in its response to the experience of deindustrialisation and the end of the mining industry in the northeast. The memorial site that has grown up in its shadow speaks of the sculpture’s power to inspire individual acts of micro memorialisation, which in turn build on the site’s creation as a place of memory and of transformation.

In a recent conversation, David and I were talking about Antony Gormley’s ‘Another Place’, a sculptural installation of one hundred cast-iron men on the sands at Crosby near Liverpool. We were thinking in particular about the micro organisms such as barnacles that have attached themselves to the sculptures, which are continuously covered by the tides, and that have become an important part of the fabric of the sculpture. David suggested that the tributes which are left as micro-memorials at The Angel could be seen in an analogous way, as practices and objects that have arisen around and in response to the Angel sculpture, and that now form a vibrant and integral part of its fabric and meaning.

References

Avril Maddrell, ‘A place for grief and belief: the Witness Cairn, Isle of Whithorn, Galloway, Scotland’, Social and Cultural Geography 10.6 (2009), pp. 675-93.