Most of the posts in this blog focus on the memorial tributes that are left in the trees, which stand immediately below The Angel of the North. A variety of notes and trinkets are regularly either suspended from the branches of the trees or placed beneath them. Less often, memorial objects are also left on, or at, the sculpture itself, and it is these tributes that form the subject of today’s post.

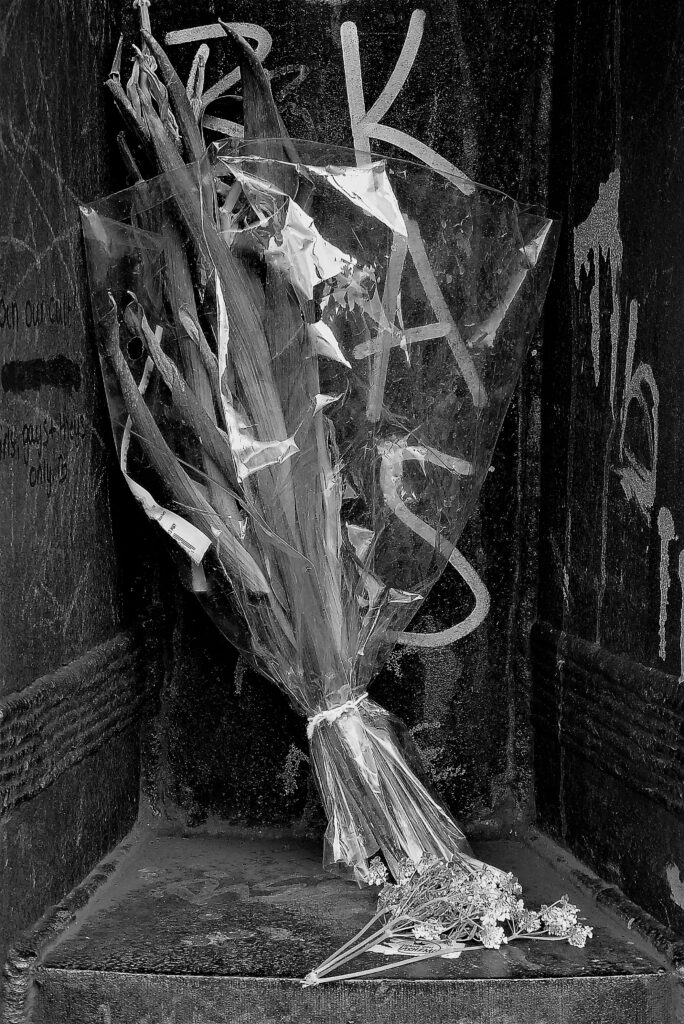

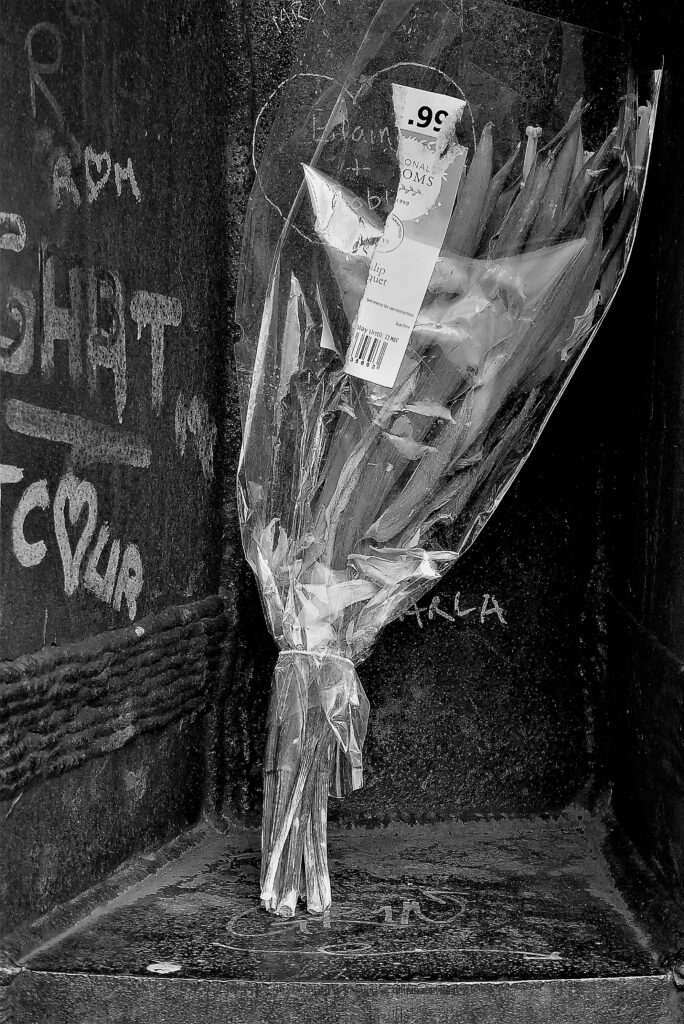

The construction of The Angel means that a series of enclosed ‘shelves’ is created where the ribbing between sections meets, and these alcoves are readily accessible at the height of The Angel’s calves. That these ‘shelves’ can be easily reached is attested to by the layers of grafitti that are inscribed there – another way in which visitors to the site leave traces of their presence behind. When I visit, I often walk round The Angel first to check whether any objects have been left there, before proceeding down to the stand of trees.

I have written in a previous post about the difficulty of being able to tell whether an object is a memorial tribute, or if it is something discarded, or perhaps something found that has been placed there in the hope that it will be reunited with its owner. I observed that this problem of identification increases on the perimeter of the memorial site in the trees, and the same issue arises when faced with those objects that have been left at or on The Angel. It can be impossible to determine sometimes why a particular object might have been left there. In this post, I therefore focus on four tributes that I believe have been left with memorial intent, even if I do not know who or what is being commemorated by them.

The first tribute is a cap and a single red rose, which were left on adjacent ‘shelves’ on The Angel (pictured above). The rose had a card attached, but I could not see if any message was written on it and I followed my usual practice of leaving the objects undisturbed. It was tempting to read the grafitti behind the objects – the ‘Jacob was here’ behind the rose and the series of three kisses inscribed above the cap – as accompaniments to the objects, but it is more likely that their placing was either accidental, or that the person, or people, who left the objects there felt that they formed appropriate backdrops for their tributes – although the accompanying image behind the rose seemed to discount that theory.

The rose was more ephemeral than the cap, and it had disappeared by the time of my next visit. The cap had been moved to the memorial site in the trees and it was hanging on a branch of the oak tree near the entrance to the copse. Over my next few visits, the cap changed position in the memorial site a number of times. I was unsure whether it was being moved by the person who had originally left it there, or if other visitors were positioning and repositioning it across the site. I found that this degree of mobility often characterised objects that were left on or at The Angel; much more so than with the objects that were left in the trees, which tended to be moved by the wind but not by other visitors.

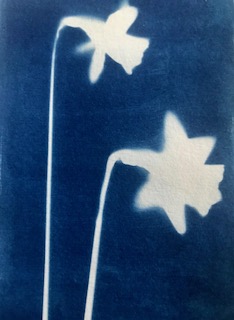

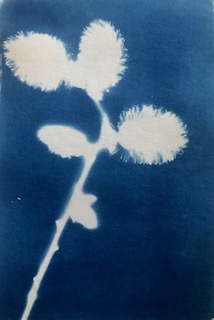

The second tribute also makes use of adjacent ‘shelves’ on The Angel, this time to place two bouquets of flowers, which were seemingly purchased on the way to the site and with the shop label partially removed. One of the bouquets is accompanied by one of the wild flowers that grows on the edge of the field on which The Angel stands. The next time I visited, there was no sign of these flowers; these seemingly quite spontaneous tributes are often ephemeral in nature. These two bouquets were left on The Angel, but it is more common to find them leaning against The Angel’s feet, at the front or side of the sculpture.

The third tribute that was left on the ‘shelves’ of the ribbing was a pair of plaster-cast wings. I spotted them as soon as I arrived, because they had been placed on the eastern side of The Angel, visible from the path that leads from the car park. Occupying a single ‘shelf’, the wings had been carefully positioned to echo but not to touch each other, and other visitors, like me, were looking at them but leaving them undisturbed.

When I returned the following week, I could see that the wings were no longer on their original ‘shelf’. Walking round to the west side of The Angel, however, I found both of the wings positioned on adjacent shelves, and arranged vertically to form a different kind of pairing.

Once again, I had no way of knowing whether the wings had been moved by those who had originally left them on The Angel, or whether subsequent visitors had altered their positioning and their placement. The movement from east to west had shifted the wings from sunrise to sunset, and I was tempted to find some meaning in this, even as I was aware that it was most likely coincidental. On my following visit, the wings had disappeared, and, even though I looked for them in the trees over succeeding visits, there was no further sign of them. This disappearance of the object was unusual, unless it was itself of a more ephemeral nature: it was more common that a tribute left on The Angel would turn up in the trees, if it was no longer visible at the sculpture itself.

The fourth tribute left on The Angel was a small, artificial candle. Smaller than the other objects, it had been positioned on The Angel’s north side, where the ribbing is narrower and the ‘shelves’ correspondingly smaller. There was no accompanying note or message, although its memorial purpose seemed clear. There was something touching in the contrast of scale between The Angel and the diminutive candle; something too, perhaps, in the way in which The Angel seemed to shelter the candle’s tiny flame and to offer it protection. I thought of The Angel, unlit at night, forming a vast shadowy presence, and I wondered if this solar candle would then illuminate a tiny scrap of the surrounding dark. There was something of the altar about this tribute; the positioning of the candle transforming the domestic ‘shelf’ into something with a more sacred resonance.

The placing of objects at or on The Angel is facilitated by the design of the sculpture itself, which, as I have noted, forms ‘shelves’ of varying depths onto which the tributes can be placed. It is nevertheless striking that the memorial tributes are more commonly left in the nearby trees rather than at The Angel itself. This might be due to practical considerations – objects left here are more exposed, both to the weather and to other visitors, and so are often moved or disappear. Objects left at The Angel accordingly tend to be ephemeral and disposable in nature – tributes such as flowers, or a candle. The exceptions to this – the cap and the plaster wings – were subsequently repositioned, whether by the same visitor/s or others, with as much apparent thought and care as when they had originally been placed there.

Why, then, do the trees rather than The Angel seem to have a gravitational pull, such that even objects placed on The Angel seem to end up there? One factor certainly seems to be the shelter that they afford from the elements, especially the force of the wind. But the trees also offer shelter from other visitors, who venture less frequently into the copse, and are less likely to disturb what they find there. Leaving a memorial tribute on or at The Angel is a more public act, even if it is conducted when nobody else is there. The memorials in the trees constitute tributes that are public and private, and that speak not only to The Angel, but also to the community of other memorial objects that they join, and by which they are surrounded.