Sounding the Angel can now be accessed in full here. In a series of four blog posts, I introduce each of the four sections of the sound work. Today’s post discusses the second part of the work, ‘Winter’. You can listen to this section here.

This is the second of four posts that share the sound work, ‘Sounding the Angel’. My last post, ‘Autumn‘, focused on the participants’ relation to the Angel of the North, asking why they had come to leave a memorial tribute at the site. This post reflects on the second part of the sound piece, ‘Winter’, which focuses on the act of leaving the memorial tribute.

Our first participant explained that he was scattering ash in memory of his wife at different locations that had been of significance to her. One of the intended sites had been Sycamore Gap, on Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland, but the famous sycamore tree that was growing there had recently been chopped down. He was on his way to the National Arboretum of Scotland, to commemorate her amid the giant redwoods that she loved, when a rainstorm came on, so he stopped at The Angel instead. Even in the pouring rain, there was a man out walking his dog , and our participant reflected on the companionship offered by The Angel site – not only from the sculpture itself, but also from the visitors who are always there, and other memorial tributes that have been left in the trees. No other people were involved in the ritual, which was described as ‘a strictly intimate affair’ .

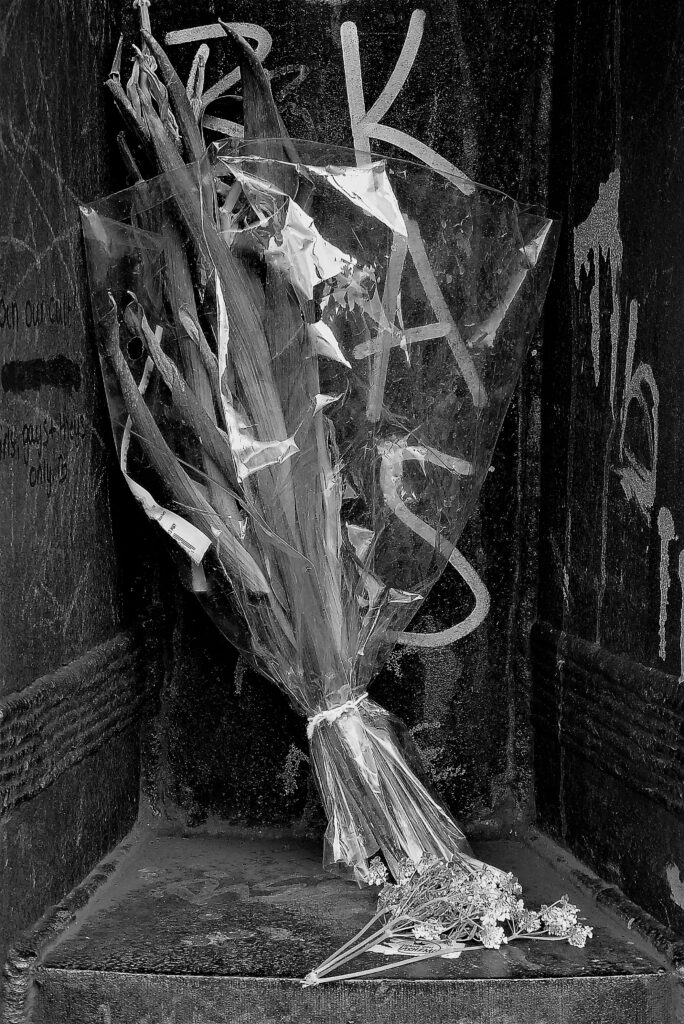

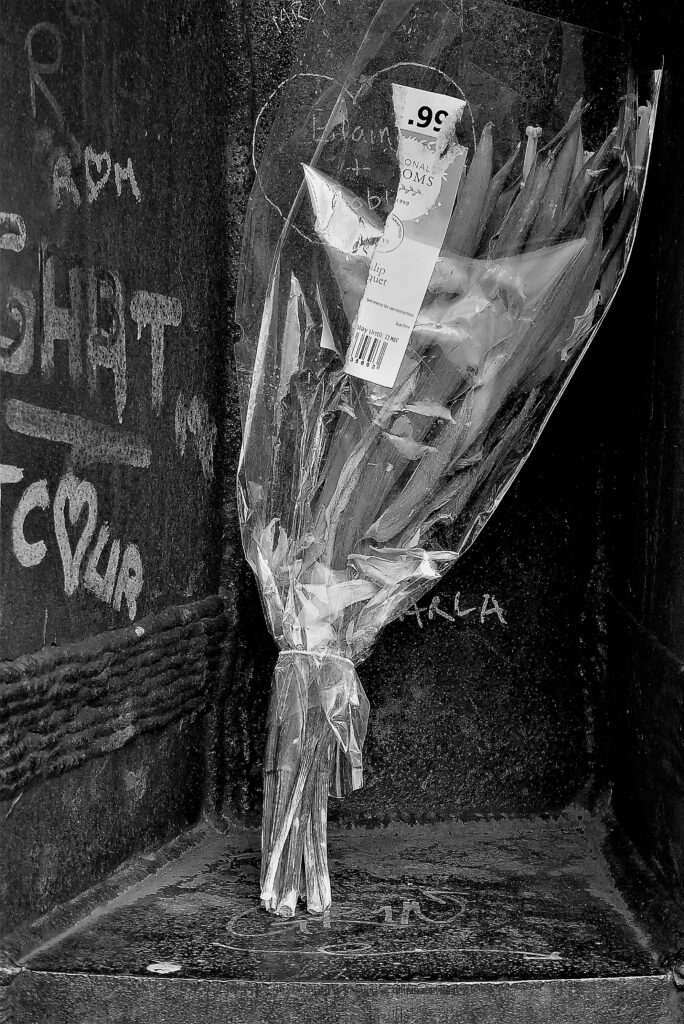

Our second participant also spoke of going to The Angel alone, to leave the tribute to her brother. Having come across clootie wells in Scotland, and the pieces of coloured cloth tied to the trees, she took the Christmas present ribbons and tied them to a tree in the copse, with the intention of adding to them on every visit, so that the tree would eventually look as if it was blossoming with new flowers. When she returned to the site, she found that some of the ribbons had gone, and also that the site was more crowded with tributes from other people. She found a different tree, on the perimeter of the memorial site, so that she could leave her tributes there, but this too was soon also in the middle of the expanding memorial. Where our first participant found comfort in the presence of the other tributes, our second participant preferred to be a little bit away from the main memorial garden. This inclination can also be seen in others when walking around the site, with some memorial tributes placed in trees that are a little distance away from the copse.

A resonance emerged between the two conversations as our participants reflected on what they had left. Speaking of the ash that formed the memorial tribute to his wife, our first participant reflected that ‘it would easily be blown away, or swept away, to be with the ghosts of the mineworkers that toiled below’. Likewise, our second participant found an unexpected comfort in her ribbons blowing away, observing: ‘wherever those ribbons are, [my brother] is there as well, and the love that we have for him and how we miss him and everything, those new places now know about [him]. I like the way mine has worked out, with the ribbons flying all over the country’. Both participants found solace in the wind’s dispersal of their tributes, seeing this as offering a connection to something larger – whether the mining community of the past, or different, unknown places, that had now become points of connection to the loss.

The impetus that led both participants to leave a tribute at The Angel was practical in nature. The first participant addressed the question of where to scatter his wife’s ashes, while the second participant faced the problem of how to grieve for her brother when there was no obvious place for her to go. The memorial site at The Angel is thereby connected to contemporary shifts in memorial practice, with a move away from the traditional cemetery plot, and with many mourners now located far away from the places that are associated with their dead. Following the coverage of this project in The Guardian, a number of people contacted me to suggest a connection between the memorial site and the tradition of rag or clootie trees. Here, one of our participants speaks of being inspired by Scottish clootie wells, and of consciously trying to recreate them at The Angel site. In my previous post, I reflected on whether the adaptation of the clootie tradition to the act of mourning might tend towards the use of more lasting or permanent fibres in the ribbon or cloth, but our participant finds comfort in the ephemerality of her tribute, as well as in the act of tying the ribbons itself.

In this section of the sound piece, you can hear recordings that David made with his contact microphones during Storm Babet. The heavy rain dropping onto the metal resonates through the structure, accompanying our first participant’s story of leaving the tribute for his wife at The Angel in the pouring rain, and suggestive both of the season and of tears.