How do you ensure that no one is left behind in making clean water and sanitation available to all? The water cycle is not a bad place to start and it can be taken both literally and metaphorically. Water is an integral part of life, and we interact with it often, including the infrastructure that delivers water to the places we live in.

To come to grips with how water exists on this planet no one part of the water cycle can be studied in complete isolation from the other. There are simply too many factors involved that affect water such as climate, pollution, water usage, wastewater treatment, water catchments and so forth.

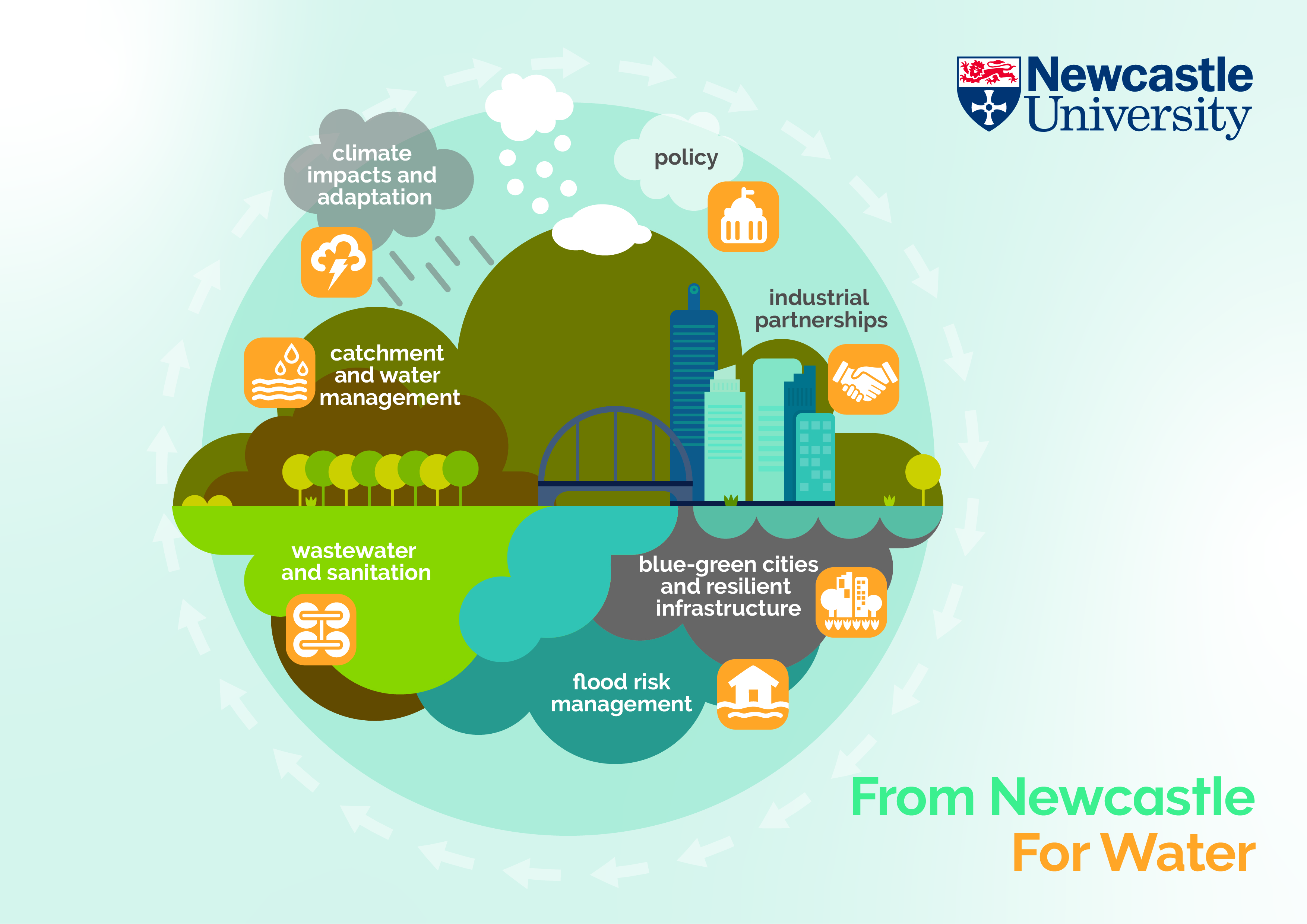

This graphic illustrates how research in different areas of water are important to the whole picture of the water system which involves human activities like industry and policy as much as ‘natural’ or non-anthropogenic ones. It provides a holistic representation of some of the key research areas at Newcastle University in water, particularly from the School of Engineering.

We think this diagram provides a useful metaphor for how water research is integrated. For example, what is done for climate impacts and adaptation is directly applicable to water resources management, including managing flood risks.

If you’re going to prepare for extreme rainfall events then advanced flood modelling tools are needed to inform your adaptation plan. The closer the simulation or scenario to the actual event as in a ‘digital twin’ (usually) the better.

Linking it to public policy ensures that planning is better informed especially if it resonates with local communities that you’re aiming to work with. Policies that don’t have at least some level of public input may not work so well.

Community charters, as the one done for the city of Newcastle through the Blue Green Cities project for example, seem a way forward because it brings together everyone on board including, utilities, business and industry.

So how about leaving no one behind?

There are many perspectives on why people are left behind in terms of resources in the first place, one of them is inequality. Low income leads to poor sanitation and an increase in antimicrobial resistance, which is not due to overuse of antibiotics alone.

Lack of sanitation has been attributed to poverty, and the people left behind in some cases live in informal settlements that are cut off from water infrastructure of any kind.

Without the right infrastructure in place, delivering clean water and sanitation is too steep of a climb, however, there are smarter ways of delivering infrastructure that are tailored to local needs. Expensive, complicated infrastructure may not always be the best way forward, especially if it cannot be maintained.

Community-based solutions may appear low-tech but are just as effective, especially if they are understood and regularly maintained by people living within the community.

Take for example a local group of women in a village in Kenya, whose actions have resulted in the delivery of water resources to residents and hospitals, as shown in this excellent subject-driven documentary.

Water infrastructure need not be expensive to work well, and many communities in low to middle-income countries are demonstrating that empowerment is possible by applying a grass roots approach that is social and technical.

In other words the communities need to be involved but the techniques which enable them to supply water must not be separate or excluded from their values. The social, technical, cultural bits all working together may make the most difference.

Traditional hard engineering approaches while powerful and a force of nature in their own right, will only get us so far in making sure no one is left behind in meeting the challenge for clean water and sanitation. The rest is up to individuals and communities, making organising at the social scale key to any solution for water.