The scene

Picture the scene; it was a sunny August Friday afternoon on the last day of a four day European conference in Dublin. We found our session venue and we organised ourselves and our resources for our workshop. Writing the conference abstract in January seemed a very long time ago, but we had spent some time since then re-visiting our understanding of our proposition which we had articulated as follows:

Visual models can be used as tools because they have the potential to facilitate effective research and practice partnership.

In our workshop we wanted to unpack this idea and create a space in which we could explore it further with the participants. So, we went armed with three examples from our own work, each one illustrating a different type of use, as well as a suite of other models on posters that we were offering as stimulus. We overcame the two problems which beset us; firstly finding that the posters had got jammed inside the cardboard tube which needed to be attacked with scissors to allow them to be levered out, and secondly realising that the scheduling of the session meant that some potential participants were already on their way to Dublin airport. On the flip side we were grateful for the 1970s classroom with breezeblock walls on which we could blu-tac our posters with gusto (we had feared one of the pristine new seminar rooms), and we welcomed our session chair (ex-CfLaT colleague Elaine Hall) and our small band of enthusiastic workshop participants.

The idea

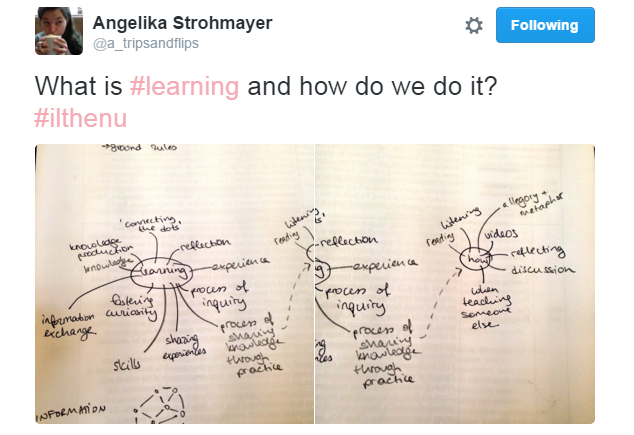

So, what do we mean by our proposition? In recent years CfLaT researchers have developed a range of visual methods to aid participation in research and our workshop extended this theme. It came about because we each had found ourselves planning or reviewing a number of our research projects which to some extent relied on partnership working, and recognising that in some of them visual representations of ideas played a key role. We consider these to be models – in the sense that the visual representations offered a way to demonstrate key concepts, allowing us to work out and share ideas that were relevant to specific contexts but could also articulate more generalizable ideas. However we also recognised that the models were rarely static but instead were active in the partnerships; they acted as tools. Our initially reflections on our experiences were grounded in theory. We suggest that tools used or created within of research partnerships are able to perform epistemic functions and having catalytic qualities. In other words they act as part of the knowledge-transfer and knowledge-building aspects of research in partnerships. They also can function as boundary objects supporting boundary crossing within research partnerships. This can be quite literal – they can physically be passed between participants whose experiences on either side of boundaries might otherwise be difficult to connect and learn from (e.g. the boundary between academic researchers and young people in their communities). During our conversations we started to develop our own conceptual lens which was built on our recent experiences.

Unpacking our thinking

We see research partnerships as sites for learning, in that they can provide opportunities for reciprocal learning, which is a way of enacting partnership. Our experience suggests that using and developing models has many potential benefits to aid partnership. These benefits include; encouraging reflexivity and criticality, adding a dynamic to dialogue, enabling mapping of experiences, providing a relational platform and acting as a visual mediation of encounters. We argue that models as tools to aid research partnerships are primarily used in three different ways, and it was this that we explored in our ECER workshop.

Firstly we consider models as tools for Application. We expressed this as applying a model to make existing theories more accessible to the participants of research and practice partnerships. The model could be inputted into the research and practice partnership at any stage, perhaps helping to create a framework for research design, or acting with explanatory power. We illustrated this through a HASS faculty PVC-funded research project in which A practice development led model for individual professional learning and institutional growth developed through Rachel’s PhD is being applied to research focus groups. In these settings it acts as a tool to stimulate debate, support reviews of current practice, and enable new learning and opportunities for practice development.

Secondly we consider models as tools for Elaboration. In our experience models can be generated and / or adapted as an inherent and developmental part of the research and practice process to scaffold learning within the partnership. We used Theory of Change as our illustration, which Karen has significant experience of. These models provide a way of encourage research partners to take an active role in conceptualising approaches to evaluation (for example of educational interventions or programmes). Developing a collaborative theory of change helps to focus participants’ thinking to reveal what might be in the black box of systems change, from inception, through to implementation and evaluation of outcomes. The process also provides a focus for dialogue and a vehicle for exposing contradiction and building consensus in partnerships.

Finally we consider models as tools for Creation. Creating new models as an outcome of research partnerships helps to synthesise and conceptualise emerging learning, allowing research partners to engage in theorising, verification and knowledge-construction allowing the development of theorised practice. To illustrate this we used the Collaborative action research model which resulted from partnership work between Rachel and independent speech and language therapists to develop a new inter-professional coaching approach.

Moving forward

So, following our workshop where are we now? Well it was reassuring that we were not laughed out of Dublin-town – while we had a small audience they each actively engaged with our ideas and started to interrogate them from early on the workshop. Luckily we had 90 minutes in which discussion could flow – a definite advantage of a workshop format over a conference paper. Each participant offered some personal insight, and in doing so revealed that they had not thought about models in the way that we had. So we at least felt we were offering them something new to take away, and indeed they offered reflections on what this might be – whether it was related to their current research or indeed their teaching partnerships. We were able to rehearse our ideas, both in our preparation for the workshop and in its execution. Taking an idea from a relatively private space to public scrutiny can generate anxiety, but also creates an opportunity for reflection, sense-making and further learning. The advantage of working together meant that one of us was able to take notes while the other focused on facilitating conversation – and soon we will find time to review what emerged and was noteworthy. Thus we have new ideas which we will take back into our own research or practice partnerships, and we also have a sense of the degree to which our thinking about models as tools to support research partnerships is valid. Plans for publication will ensue.

Written by Dr Rachel Lofthouse, Head of Education and Karen Laing, CfLaT Senior Research Associate, Newcastle University.

References for the 3 models:

Practice development led model for individual professional learning and institutional growth

- Lofthouse, R. 2015. Metamorphosis, model-making and meaning; developing exemplary knowledge for teacher education. PhD thesis. University of Newcastle. https://ncl.ac.uk/dspace/handle/10443/2822

Theory of Change

- Laing, K. and Todd, L. eds. Theory-based Methodology: Using theories of change in educational development, research and evaluation. Research Centre for Learning and Teaching, Newcastle University. http://www.ncl.ac.uk/cflat/publications/documents/theoryofchangeguide.pdf

Collaborative action research model

- Lofthouse, R., Flanagan, J. and Wigley, B. 2015 “A new model of collaborative action research; theorising from inter-professional practice-development”, Educational Action Research, published online 2015 http://tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09650792.2015.1110038