In this Lug post, Ally Keane writes about her new doctoral research that is funded through the Northern Bridge doctoral training partnership. Ally will be using oral history to work with users of augmentative voice technologies and their families.

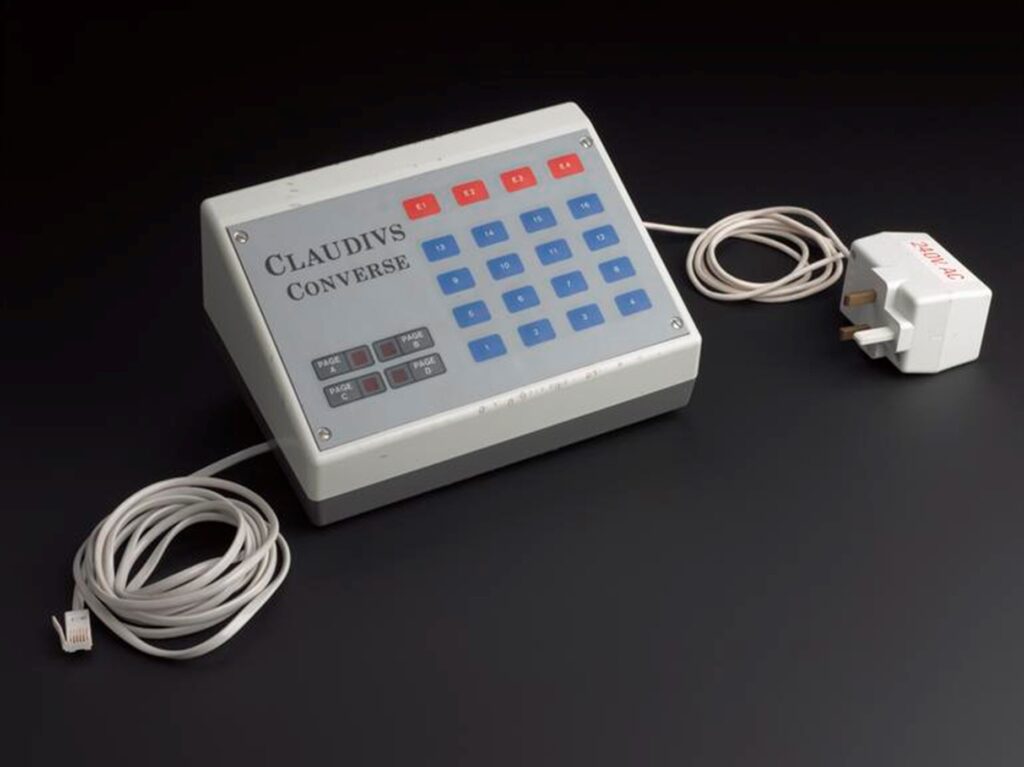

‘Electronic Voice.’ Image of Lightwriter SL35 in carry case. Device exhibited at National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh. © National Museums Scotland.

Oral historians have rightly stressed the importance of tone during interviews, which provides additional context to what the interviewees say.[1] My dissertation will investigate individual and family experiences of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) and will explore how oral history methodology can be adapted to suit the voices of AAC users as AAC produces monotone, evenly timed speech, which lacks the typical cues (such as pitch, timing, pausing/phrasing) that interviewees usually provide. To aid these aspects of oral history interviews, video recording will be used to see facial expressions, gestures, and posture to help decipher emotional states which are minimally expressed using AAC devices. This multidisciplinary approach will also examine the technological history and intersubjectivity of artificial voice, voice and its impact on identity, and develop a new oral history methodology attuned to the specificity of AAC voices.

AAC technologies first emerged in the 1950s and have developed to become the high-tech forms we’re familiar with today due to the increased battery power and smaller microprocessors which became available from the 1960s onwards. Histories exist for other assistive technologies (such as hearing aids and prosthetic limbs) including technologies and user experiences, a systematic historical account of AAC has yet to be written, and there is silent near silence on user, family, and carer experiences. My project uses oral history to follow medical history’s turn towards recovering patient experiences and voices and disability history’s emphasis on disabled people’s experiences and agency.[2]

Alongside the use of archival materials, I’ll undertake and analyse oral history interviews with AAC users and those closest to them. I hope to undertake c.20 interviews with AAC users and c.10 with family members, friends, or carers (i.e., those people who also usually become users themselves by aiding their loved ones to use their devices), recruiting through already established contacts as well as reaching out to charities and advocacy groups (such as Communication Matters).

I am looking forward to getting started on this work, after examining user involvement in the creation of AAC devices in my earlier research; it’ll be great to give users even more of a voice to share their experiences. I hope this new research will not just be of interest to me but will be useful for historians, as well as speech and language therapists, occupational therapists and other health professionals.

[1] See for example Anne Karpf, “The Human Voice and the Texture of Experience,” Oral History 42:2 (2014), 50-55 and Shelley Trower, Place, Writing, and Voice in Oral History (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

[2] Flurin Condrau, “The Patient’s View Meets the Clinical Gaze,” Social History of Medicine 20:3 (2007): 525-40; Roy Porter, “The Patient’s View: Doing Medical History from Below,” Theory and Society 14 (1985): 175-98 and Catherine J. Kudlick, “Disability History: Why We Need Another “Other”,” The American Historical Review 108:3 (2003): 763-793.

Can you provide insights into the diversity of authors contributing to the blogs, such as students, faculty, or external experts?

We do aim to but sometimes miss that in the introduction. So thank you for the reminder.