Here, Sue Bradley finds some half-forgotten animals and resolves to listen out for more. Sue is a member of the Newcastle University Oral History Unit and Collective and a Research Associate on FIELD (Farm-level Interdisciplinary Approaches to Endemic Livestock Disease) in Newcastle University’s Centre for Rural Economy. Her article, ‘Hobday’s hands: recollections of touch in veterinary practice’ appeared in Oral History, vol 49, no 1, 2021.

By the time I realised my boiler was broken, the papers stored in a carelessly open plastic box underneath were sodden through – heaps of interview extracts that had defeated me years before when editing a book from the British Library’s Book Trade Lives oral history collection.[1]

Frank Stoakley, born in 1905, is one of the oldest Book Trade Lives interviewees.[2] In 1920 he started work at Heffer’s bookshop in Cambridge, where he later built a science department of international repute. Sometime before the first world war, his father, who ran the family bindery business in Green Street, had been shocked by the loss of rare books after ‘some fool left the tap on’ in rooms above the university’s science laboratories. Together with his brother, an assistant to the professor of chemistry, William Pope, he had gone on to invent a technique for repairing flood-damaged books. This, Frank explained, had entailed bathing them in several solutions to separate and clean the pages before hanging them up to dry. I lifted soft wodges out of the box, peeled the sheets gently apart and pegged them on the washing line. Once dried, the print was blurred but still distinct, and there, exposed by the springtime sun, were animals that had been hibernating all along. I recognised Vicky the terrier, some leopards, and a cat called Bang who had lived with Leonard Woolf.

However hard I tried, I hadn’t been able to fit animals into that book without tagging them on like curiosities. Then, shortly before they re-surfaced, I had begun to read about animal history, a thought-provoking and increasingly influential field.[3] It proposes a shift akin to the move to ‘history from below’ but, rather than hierarchies, it envisages networks where human and animal lives are dynamically interconnected.[4] From that perspective I see that the problem of fit lay less in the structure of the book than in the original interviews, many of which I had been responsible for. As far as I can remember, I rarely asked directly about animals. They were interesting when they appeared but I didn’t understand them to be historically significant, so if they came into the conversation it would be incidentally, not unlike women and domestic staff previously. At one time, oral historians researching home life were advised to ask specifically about the latter, as interviewees might not otherwise think to include them. Oral history has never precluded accounts about those who cannot speak for themselves; one person’s recollections can help us imagine other lives too.

The volume I eventually produced contains a bookseller’s description of men at work in the packing room of the London bookshop of Bumpus in the 1950s, where wrapping from in-coming goods was recycled for out-going orders: ‘They would select pieces of paper and corrugated cardboard and make a parcel. It was all done by eye. And they used string in those days. Their packages were beautiful to look at.’[5] A room full of paper and cardboard and string? Why didn’t I think to ask about mice? That might have led to other creatures – a shop cat? A customer carrying a marmoset?[6] If recollections of animals had been embedded in context like that at the interview stage, they would have fitted naturally into the book and, more importantly, broadened the vision of life that the archive collection affords.

Re-reading Frank Stoakley’s transcript, I am struck by yet another detail. His father, he says, was skilled in cutting images from coloured leathers to decorate the bindings for books of wealthy clients: ‘The racing men wanted their star horse […] and ladies wanted their pet dogs.’ It is a telling picture of the firm’s clientèle and the creatures that they prized.

And the possible cost of this painstaking work? Frank does not mention – nor did I think to raise – the question of anthrax, a lethal disease of animal origin prevalent at the time in the wool and leather-working trades.[7] As Melanie Challenger says, we’re fond of the notion that being human somehow provides ‘a magical boundary’.[8] Yet human life does not exist apart from animals. Imagine the history that hears them in workshops and libraries and senses their traces in vellum and glue.

[1] The British Book Trade: An Oral History, British Library, 2008/2010 was edited from the British Library’s Book Trade Lives collection of audio interviews with publishers and booksellers: https://www.bl.uk/collection-guides/oral-histories-of-writing-and-publishing.

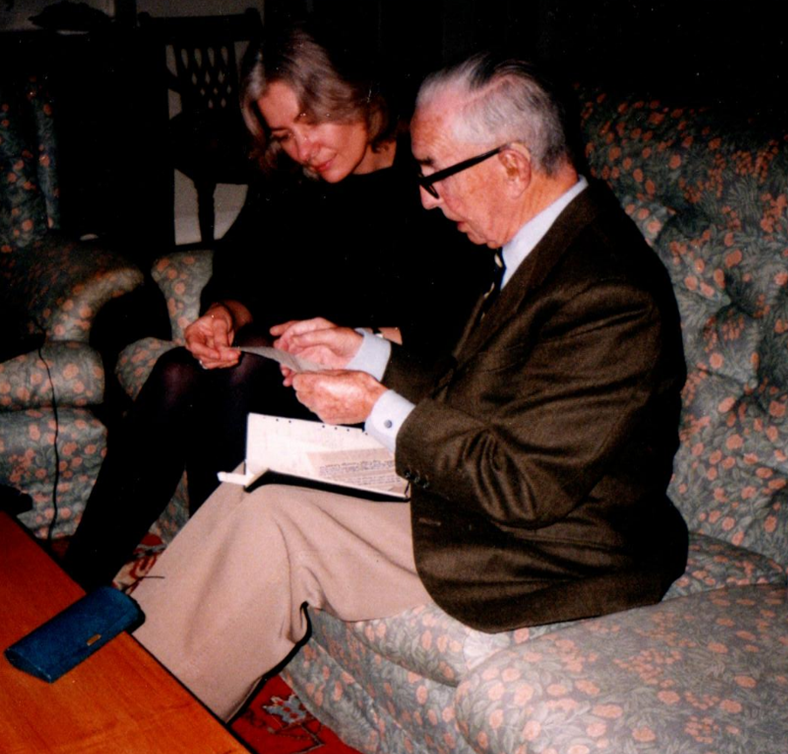

[2] Frank Stoakley interviewed by Sue Bradley, British Library catalogue reference: C872/04.

[3] See https://www.britishanimalstudiesnetwork.org.uk/; https://animalhistorygroup.org/; https://networks.h-net.org/h-animal.

[4] For a useful overview see Chris Pearson, ‘History and Animal Agencies’, in Linda Kalof (ed), The Oxford Handbook of Animal Studies, 2017.

[5] Michael Seviour quoted in The British Book Trade, 2010, p.72.

[6] Bumpus served a grand and bohemian clientèle at a time when monkeys were not uncommon pets.

[7] See Caroline Steedman, Dust, Manchester University Press, 2001, pp. 23-25.

[8] Melanie Challenger, How to Be Animal: A New History of What it Means to Be Human, Canongate, 2021, p.2.