The remarkable Uruguayan essayist and journalist Eduardo Galeano was a relentless dissector of what Serge Halimi of Le Monde Diplomatique has called ‘the inequality machine [that] is reshaping the planet’. Here is an example, written about Caracas circa 1971. Even before the 1973 quadrupling of oil prices, Venezuela’s oil production had made it one of the least poor economies in Latin America. However, most of the revenues were extracted by transnational corporations like Exxon, Gulf Oil and Royal Dutch Shell, and what wealth remained in the country was highly concentrated. ‘While the latest models flash like lightning down Caracas’s golden avenues’, wrote Galeano, ‘more than half a million people contemplate the wasteful extravagance of others from huts made of garbage’. The relation between automobiles and social exclusion, both symbolically and by way of transport infrastructure choices that are literally cast in concrete, was a consistent theme in Galeano’s work. ‘[T]he city is ruled by Mercedes-Benzes and Mustangs’, he wrote. ‘In Caracas, enormous and expensive machines abound for producing pleasure or speed or sound or light. Like poor frightened ants we face these machines and wonder: “Jesus, is each of these really worth more than me?”’

This sounds like a rhetorical question, but decades later, it provides a useful window into twenty-first century inequalities. At the start of this decade, the best available research suggests that the median household wealth of the UK population was around £80,000. In other words, half of all UK households ‘were worth’ less than that. A knowledgeable petrolhead can stand on a kerb in London, and many other major British cities, and in ten minutes or so point out numerous cars and SUVs that cost more than £80,000. (Non-petrolhead readers who doubt this should pick up a copy of Evo or Octane at their local newsagent’s.) So the answer to Galeano’s question, in the UK context, is clearly affirmative. Such grounded comparisons arguably tell us more about the real world of inequality than abstractions like Gini coefficients.

Galeano’s Open Veins of Latin America appeared in English in 1973, just before the US-supported coup d’état that turned Chile into a bloody showcase for neoliberal policies. It was a text in the undergraduate development studies course that forever transformed my provincial outlook on world affairs. I have been re-reading his more recent Upside Down: A Primer for the Looking-Glass World, which appeared 20 years ago – and, chillingly, reminds us that a 1997 New York Times article praised the coup as beginning ‘Chile’s transformation from a backwater banana republic to the economic star of Latin America’. The book swings between savagery and satire (on the media and Monica Lewinsky: ‘I think something else happened in 1998, but I can’t remember what’) and I find myself wondering how Galeano – who died in 2015 – would regard the era of Brexit, Trump, and a decade-long retreat from the always fragile institutions of democracy into the authoritarianism that repeatedly forced him into exile.

He noted that Saudi Arabia’s role as one of the world’s largest customers for the arms trade appeared to confer immunity from criticism of its deplorable human rights record. Plus ça change … Already, Galeano was concerned about the spread of surveillance. ‘Is there an eye hidden in the TV remote control? Ears listening from the ashtray?’ What would he make of Alexa? Or of the fact that it is possible to access detailed personal information about almost 300,000 people (contacts of contacts) through a single Facebook account, as the New York Times has shown, and few users seem to care?

Galeano memorably described globalisation as ‘a magic galleon that spirits factories away to poor countries’, noting that the resulting ‘[f]ear of unemployment allows a mockery to be made of labour rights. The eight-hour day no longer belongs to the realm of law but to literature, where it shines among other works of surrealist poetry,’ as ‘the fruits of two centuries of labour struggles get raffled off before you can say good-bye’. Here is one of several sobering reminders that key understandings of how the inequality machine operates were in place two decades (or more) ago; many social scientific advances since then involve refinement and body counting.

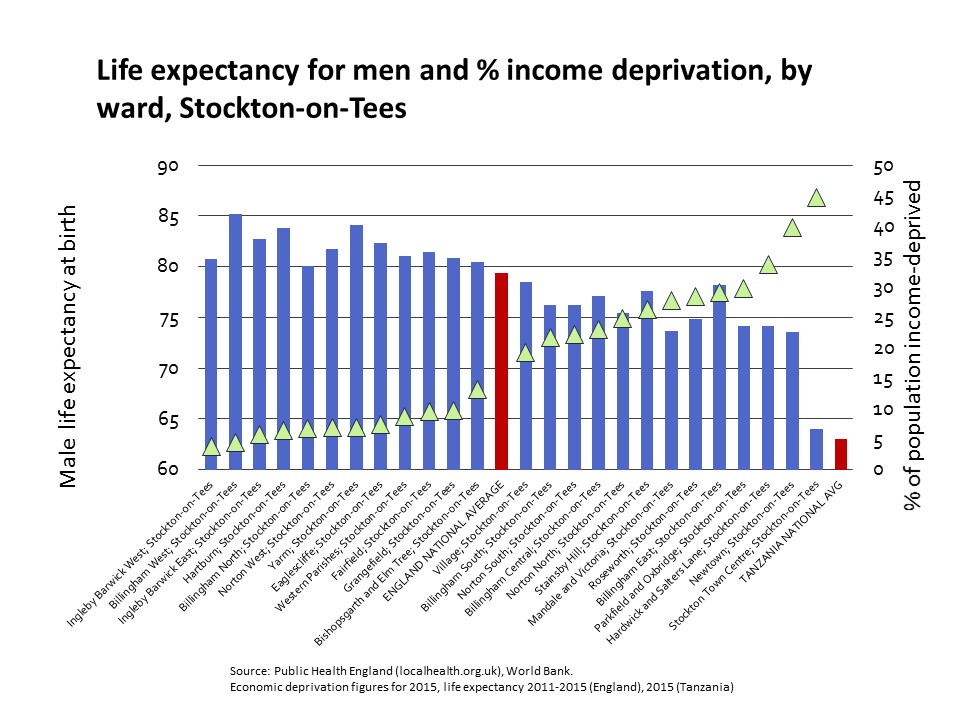

Galeano was similarly eloquent about the dangers of finance capitalism, as it shifted power and accountability towards ‘the markets’ that often dictate terms to national governments, and spawned a proliferation of tax havens and obliging facilitators seeking to protect kleptocrats’ looted billions. How would he now regard the revelations in the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers? Or look back on the financial crisis starting in 2007 that turned into a US$14 trillion hostage taking that debilitated many national economies, ratcheted up inequality and created the political opening for the destructive post-2010 trajectory of UK austerity? Galeano correctly notes that Margaret Thatcher ‘ran a dictatorship of finance capital in the British Isles’; this was the start of a rapid rise in inequality … but what would he make of Danny Dorling’s recent argument that the situation worsened on New Labour’s watch? And how would he respond to an inequality in male life expectancy at birth in the small local authority of Stockton-on-Tees, where I live, that by 2015 was comparable to the difference in national averages between England and Tanzania? This is another one of those important grounded comparisons.

The World Health Organization’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health reminded us a decade ago that health inequalities are underpinned by ‘the inequitable distribution of power, money and resources’. Reducing those inequalities first of all demands speaking truth about power. Galeano excelled at this, sometimes at considerable cost to his own safety; scathing description of the impunity enjoyed by the powerful was a consistent theme in his writing about Latin America, both during periods of dictatorship and after transitions to democracy. He might have been pleased by today’s partly successful challenges to the massively corrupt Odebrecht combine , while simultaneously appalled by the failure to act on the continuing scandal of tax havens and by the alliance of big data and big money in the dissemination of disinformation and ‘fake news’ through social media. This is a new form of coup d’état that social scientists are still learning to take seriously.

In these times of cynicism and resignation, the example of Eduardo Galeano’s courage and moral imagination is more valuable than ever.

Key references

Galeano, E. (1973; Spanish publication 1971). Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent [tr. C. Belfrage]. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Galeano, E. (1992). We Say No: Chronicles 1963-1991 [tr. Mark Fried and others]. New York: W.W. Norton [this is the source for the Caracas description].

Galeano, E. (2000; Spanish publication 1998). Upside Down: A Primer for the Looking-Glass World [tr. Mark Fried]. New York: Picador.