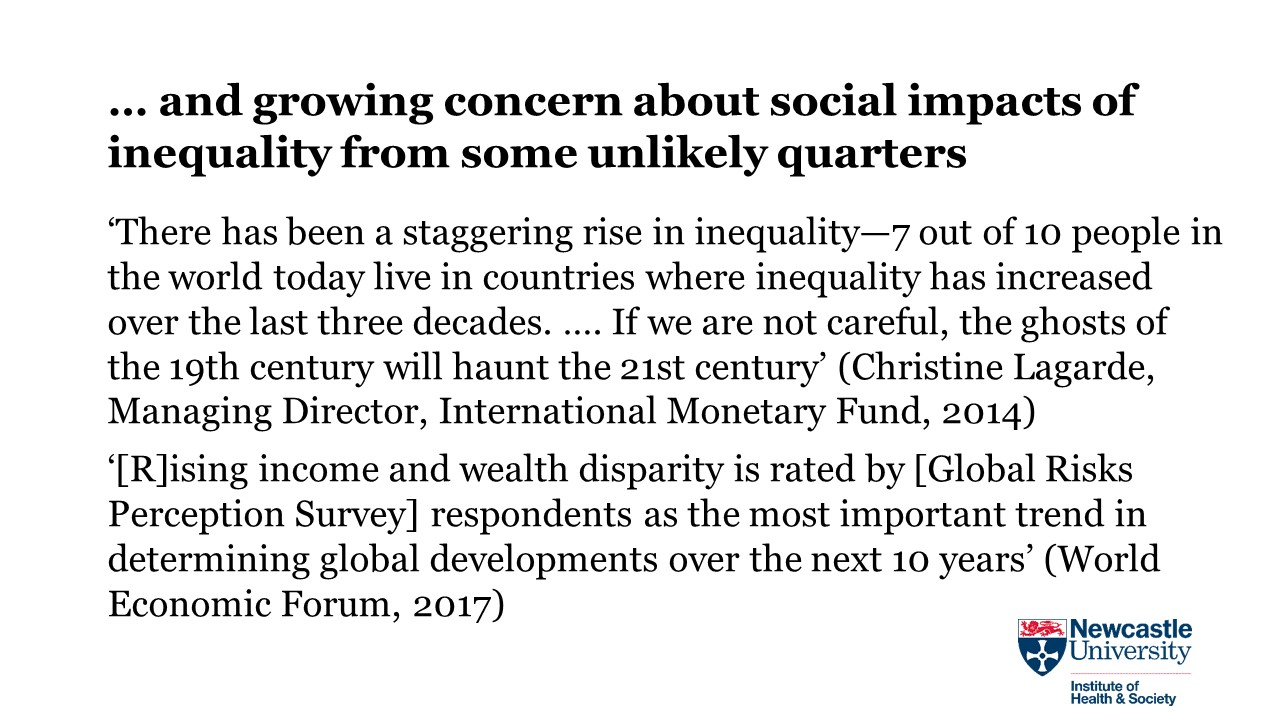

We hear much talk now of a climate emergency. As I was revising a talk I give frequently on ‘global health in an unequal world’, I realised that there is no talk of an inequality emergency, either globally or close to home, although the same macroeconomic trends and political choices driving increased inequality within national borders and on a variety of smaller scales are often involved wherever on the map one happens to look. (On these inequalities at metropolitan scale, I cannot recommend too highly photographer Johnny Miller’s compelling aerial images.)

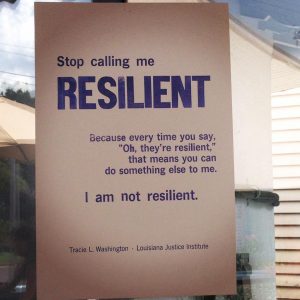

Why is there no talk of such an emergency? Many manifestations of climate change occur on a scale that makes them fodder for our spectacle-hungry visual media: think Californian and Australian wildfires; collapsing glaciers; and catastrophic damage from hurricanes and floods. The casualties of inequality tend to be smaller in scale and less visible: the lives ended sooner and more painfully than they should have been because of the accumulated damage done by relying on food banks and fearing the ‘brown envelope’ that initiates the vicious privatised process of fitness-for-work assessments here in the UK, or the estimated 300,000 women per year who die in pregnancy or childbirth from causes that are routinely avoided in the high-income world. Academically, it may be effective to compare the annual toll from death in pregnancy and childbirth to the crash of two or three airliners every day of the year, as a colleague and I have done, but such comparisons have little salience in the broader, media-corrupted world of political priorities.

Relatively vast resources have been devoted to climate science – the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is the world’s largest-ever scientific collaboration – and climate researchers long ago realised that just generating more evidence was never going to be enough to generate the change needed. So many became advocates, for example tracing 63 percent of cumulative worldwide emissions of carbon dioxide and methane between 1751 and 2010 to just 90 massive state- and investor-owned corporations (and their customers, of course). More recently, another group of authors (supported by more than 11,000 signatories) argued that ‘Scientists have a moral obligation to clearly warn humanity of any catastrophic threat’. Researchers on health inequalities, in particular, have generally been more circumspect. In the UK, advocacy that looks far enough ‘upstream’ at the economic and political substrates of health inequalities – more on that point later – is unlikely to be acceptable to agencies of the capitalist state and the trustees of billionaires’ fortunes whose funding priorities shape the direction of academic research and the career paths of academics. And the health inequalities of greatest concern, by definition, do not affect ‘all of us’. Whether the consequences of climate change will genuinely do so is too complex a question to be investigated here, but the question is well worth asking. Certainly, its effects will be felt first and worst by those least implicated in its origins.

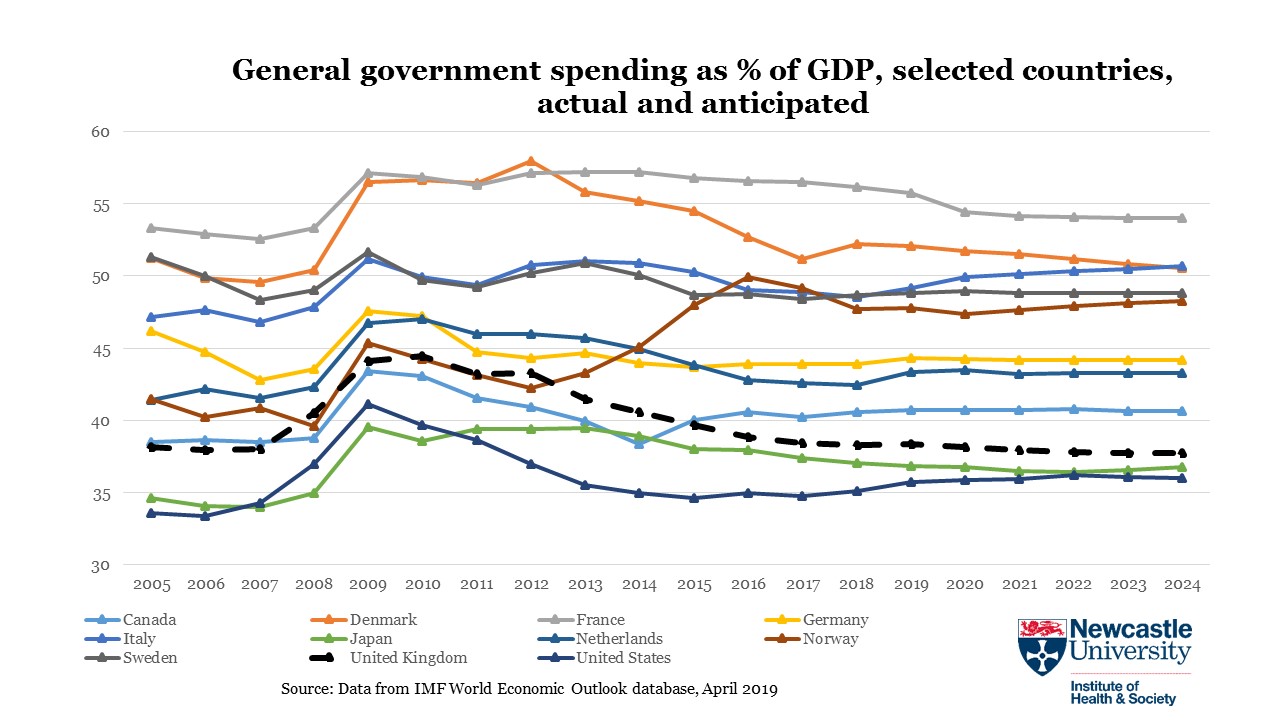

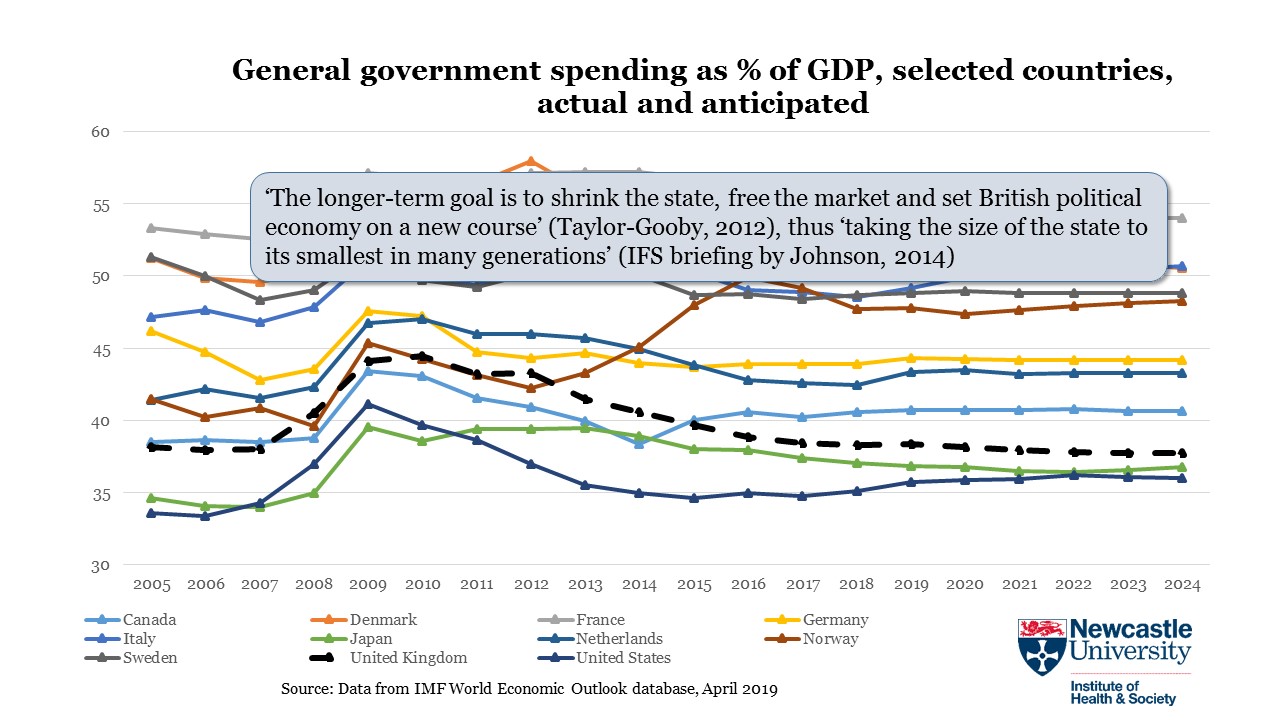

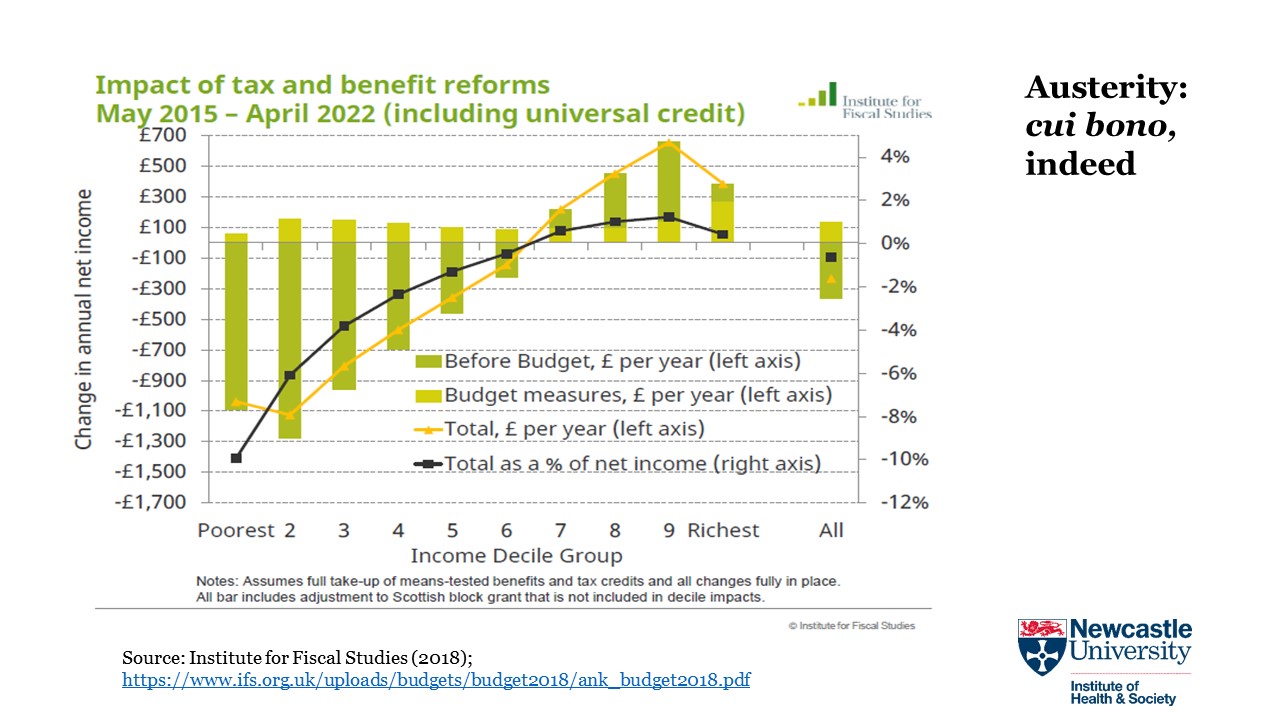

Another issue is the decades-long rhetorical and ideological Thatcherite drumbeat that ‘there is no alternative’ to rising inequality and the policies that drive it. This problem is particularly acute with regard to the austerity that has been thoroughly discredited in terms of the macroeconomic objectives of sustaining growth that it was supposed to achieve, whether in the era of World Bank and IMF-mandated structural adjustment or, more recently, in post-2010 responses to the financial crisis. As Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Krugman commented in the run-up to the 2015 UK election: ‘All of the economic research that allegedly supported the austerity push has been discredited. On the other side of the ledger, the benefits of improved confidence failed to make their promised appearance. Since the global turn to austerity in 2010, every country that introduced significant austerity has seen its economy suffer, with the depth of the suffering closely related to the harshness of the austerity’. Post-2015, of course, austerity in the UK became harsher still, demonstrably redistributing income and resources upward within British society, through both tax and benefit ‘reforms’ and savagely destructive cuts to local authority budgets.

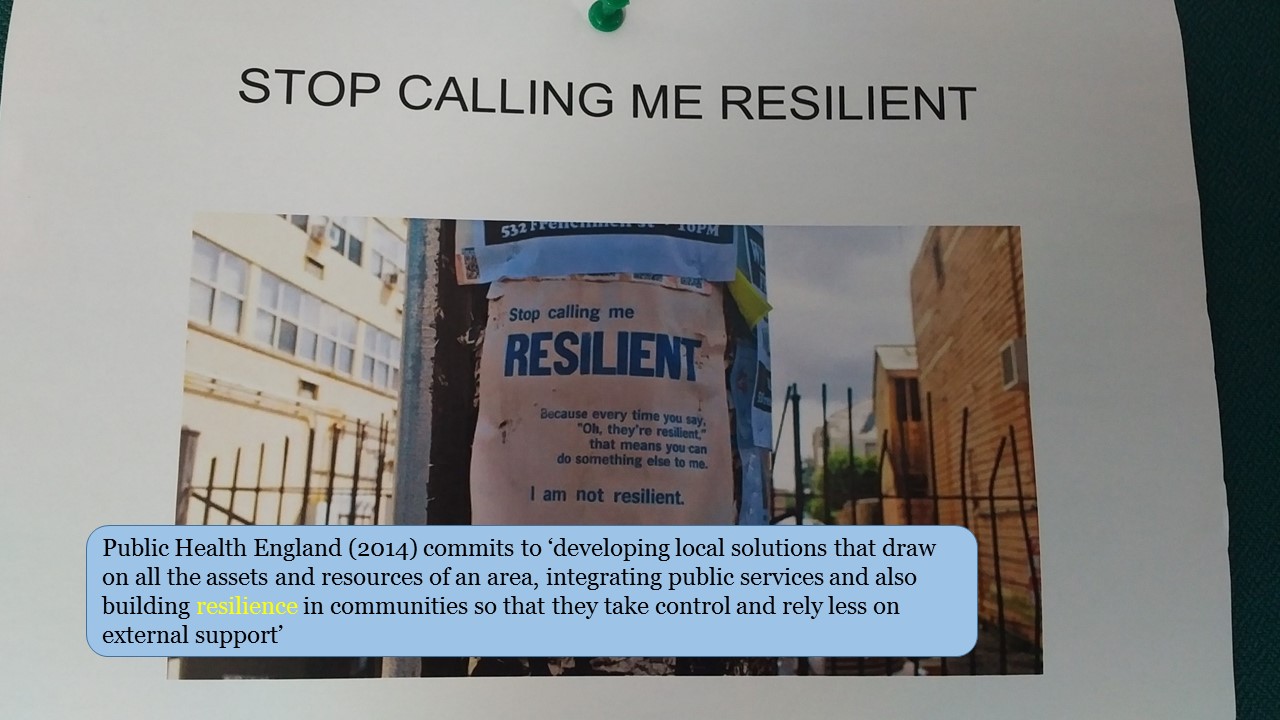

Now, austerity has become normalised; it is part of the quotidian policy landscape to the extent that we are almost no longer capable of rage when the strutting, glossy Home Secretary straightfacedly claims that poverty is not the government’s problem, when the evidence is overwhelming that post-2010 public policy has systematically and premeditatedly made the problem worse. Despite the best efforts of the fossil fuel industry, we can imagine a decarbonised economy, even though we may not be able to specify its details. Too many of us now have difficulty imagining economic systems that do not operate as what Serge Halimi, the editor of Le Monde Diplomatique, has called an ‘inequality machine’. A powerful antidote to this well-funded intellectual cauterisation is the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s 2017 blueprint for a global new deal. How many global health researchers have read it, I wonder? How many medical or MPH students have been asked to do so?

Back to the view looking upstream. Failure to understand and declare an inequality emergency reflects the success of neoliberalism or ‘market fundamentalism’ as a global class project of restoring inequality and the privileges of the rich to the levels that prevailed before what has been called the ‘great compression’ that reduced inequality after World War II in much of the high-income world, and inspired egalitarian visions far outside it. The evidence on this point can’t even be summarised here – I am glad to provide key sources – but in the context of the work that academics do, two decades of marketisation in British universities must be understood as part of the project. Centrally funded institutions that served a public educational and scholarly purpose were dismantled, replaced by corporate-style enterprises organised around generating income from deep-pocketed funders and indebted students, with careers often ended by failure to put out salable products.

Isn’t this a form of conspiracy theory, you ask? Empirically, the best rejoinders come from the work of journalists like Jane Mayer and historians like Stefan Collini and Nancy MacLean. Conceptually, an especially apposite riposte comes from the brilliant legal historian Douglas Hay, who established himself in the field with the research that underpinned the following conclusion: ‘The private manipulation of the law by the wealthy and powerful’ in eighteenth-century England ‘was in truth a ruling-class conspiracy, in the most exact meaning of the word. …. The legal definition of conspiracy does not require explicit agreement; those party to it need not even all know one another, provided they are working together for the same ends. In this case, the common assumptions of the conspirators lay so deep that they were never questioned, and rarely made explicit’ (1). Enough said.

(1) Hay, D. Property, Authority, and the Criminal Law. In D. Hay et al., Albion’s Fatal Tree: Crime and Society in Eighteenth-Century England (pp. 17-64). New York: Pantheon, 1975,