In these times of plague, at least as they are categorised by some, spilling more digital ink on COVID-19 smacks of either hubris or irrelevance, and many others are better qualified than I to comment on the outbreak’s epidemiological dimensions – although, interestingly enough, they don’t always agree, and media are stretching the category of ‘scientists’. In keeping with the blog’s theme, here are a few equity-related observations.

1. In some jurisdictions, the outbreak is a neoliberal epidemic – the term Clare Bambra and I coined in 2015 – for at least two reasons. The first of these is the lack of access to paid sick leave for literally millions of low-wage US workers in retail, hospitality, and grocery sectors who either have no entitlement to paid sick leave or do not think they do, as reported by The New York Times. Of course, in the real world, for workers without a strong union this ‘entitlement’ is really at the employer’s discretion, regardless of what the law says. In the UK, the fusion of executive and legislative power gives the government of the day the ability to remedy the comparable problem instantly, if it chooses to do so. Will it?

The current outbreak is also a neoliberal epidemic because of reliance on a profit-motivated pharmaceutical industry for vaccine development. A recent journal article points out that this model for vaccine development has systematically hindered the development of vaccines for so-called neglected diseases; it may now be doing so with regard to COVID-19. In a long and important piece in The Guardian on 27 March, US researcher Peter Hotez described ‘a broken ecosystem for making vaccines’, and claimed that he might have had a COVID-19 vaccine to offer today if his team had been able to find funding for a clinical trial based on their previous (2011-2016) research on SARS. If we take seriously the broadly shared view in political theory that the most basic prerequisite for political legitimacy is a government’s ability to protect its subjects against basic threats to life and security, then the development of scientific capacity for developing diagnostics and vaccines from basic research through to production and free, not-for-profit distribution should be regarded as a national security imperative for countries able to support such initiatives, and as a development assistance priority. Will this lesson be learnt from COVID-19?

2. Focussing on the UK context, we are now seeing the consequences of a decade of austerity during which the NHS was starved for resources and the budgets of the local authorities that since 2012 have had statutory responsibility for public health have been gutted. It remains to be seen whether the NHS will be able to cope, and how high the casualty count will be both among those infected with COVID-19 and those whose care needs are displaced by COVID-19 patients in intensive care units. Rest assured, there will be casualties. In the United States, journalist Laurie Garrett has been warning for decades about the dangers of neglecting domestic public health infrastructure. In January of this year, she broke the important story that President Trump had disbanded the country’s pandemic response capability. Some mainstream media, although by no means all, have since picked up the story. Clearly, this was regarded as less important than covering promises of building big, beautiful walls to keep out threats originating in deranged racist imaginaries. Our media in the UK, and what has passed for a political opposition over the past decade, have not done a whole lot better.

3. At this writing, one UK proposal is to respond to the outbreak by isolating people over 70 in their homes for up to 16 weeks, ‘for their own protection’, which among other shortcomings defies every principle of natural justice. At this writing, it is unclear how draconian the restrictions would be, but if they are implemented, then one wonders how many deaths of despair will result not from COVID-19 infection, but from that isolation in the context of a care infrastructure that is completely unable to provide necessary support – again, after a decade of austerity.

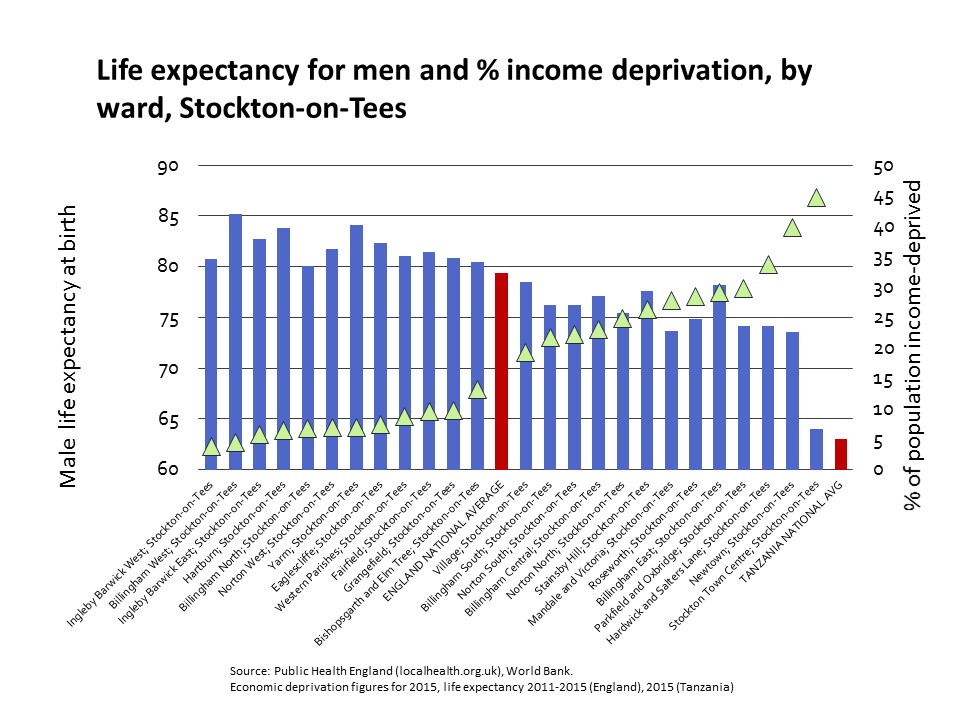

Over the longer term, the economic impacts of the pandemic may prove to magnify health inequalities in ways that are as yet impossible to predict. For example, what happens if lengthy school closures result in job losses for parents choosing between work and leaving their children home alone? What happens to literally millions of workers in (initially) the transport, hospitality and retail sectors as their jobs disappear? What happens if, or more probably when, equity market declines mean that defined-contribution pension plans across the high-income world collapse in value and defined-benefit plans can no longer meet their obligations and face insolvency?

It is possible to envision creative and progressive (as the term is used in public finance) policy responses to all these questions, and other related ones. An International Monetary Fund researcher has called for ‘substantial targeted fiscal, monetary, and financial market measures to help affected households and businesses’ (author’s emphasis). Whether such policies will prove to be politically viable domestically and internationally given the sums involved – realistically, into trillions of US dollars – and the desirability of strongly progressive finance mechanisms is quite another question. Within their own borders, both the United States and the United Kingdom have in recent years systematically and intentionally magnified inequality and redistributed resources and opportunity upward within their social structures. Time will tell.

This post was selectively updated on 29 March; many aspects have now been overtaken by events.