[Disclaimer: This is a very early take on my ongoing research. I haven’t yet had a chance to work in detail with the interview transcripts or fully analyse the questionnaires – this post is based on my immediate reflections on the research as it progressed and as I began to identify themes and ideas. It is based on a paper presented at the RGS-IBG Annual Conference in Cardiff in August 2018.]

Introduction

The “playing out” movement started around 2009 in Bristol, created by two mothers, Alice and Amy, on their street, in the hope that their children might have some of the same opportunities to play out, on their doorsteps, as Alice and Amy did. By July 2018, over 800 streets had started playing out regularly, across 77 UK local authority areas, including Hackney, Brighton, Leeds, Hull, Edinburgh, and North Tyneside, and the movement had also spread to towns and cities in Australia, the US, Spain, Romania, Germany and more. The playing out model rests on short, regular, licensed and stewarded road closures, giving children the chance to play safely near home and giving neighbours the chance to meet right on their streets.

The rise of “playing out”, as a movement, reflects the documented decline in autonomous street play, as the risks (Gill 2007) of cars, strangers and pollution, in particular, and growing pressures on children’s and parents’ free time (Holloway and Pimlott-Wilson 2014, 2018) seem to have reduced parents’ inclination to allow or enable their children to play out on their streets. Within a generation or two, the possibility for children to play out freely and safely has all but disappeared in many parts of the country (though this appears to be a pattern refracted by class and by built environment, in different ways).

There has already been a considerable amount of research about the renewed playing out phenomenon, documenting the benefits for children’s levels of physical activity and health, for their friendships, for the very local environment, and for the sense of community and belonging on the streets involved. The project on which this blog post reports picks up on this final aspect in particular and shifts the focus slightly away from children and their geographies to think about adult participants too, to ask how regular playing out sessions change the nature of everyday relationships on the streets involved.

The Research Context

At the heart of this project is an idea of everyday relationships. Borrowing ideas from the British object relations school, I use a conceptualisation of relationships, with intimate and imagined others, as the environment within which we find ways of going on being. As Gomez (1997, 2) argues: “the need for relationship is primary”. In this conception, it is the relationships around us that contain and facilitate us, help us to go on being. This is an idea developed, within geography, by Steve Pile (1996, 12) who explores the building of ‘secure personal geographies’, such that a “sense of a solid, shared world and stable sense of ourselves within that world leads to psychic and physical survival”. These ideas are developed here alongside a considerable literature which highlights and explores the key connection between children, play and streets and their everyday relationships. The articulation between community and play has been the focus of series of reports by Play England in the context of their annual Play Day events, and this has been explored more and more through debates around the child- or family-friendly cities. Rather than review the literature as a whole, there are a number of ideas to draw out here:

Firstly, it is argued that there is a symbiotic relationship between play and our recognition of and participation in our everyday spaces and environments – our own streets are at the heart of our explorations of and relationships with the world and the ability to play in them is critical to our sense of belonging to and learning within them. Stuart Lester and Wendy Russell state clearly that “play is the principal way in which children participate within their own communities” (Lester and Russell, 2010, x) and Tim Gill, in a quote cited regularly in support of street play, insists that “the street is the starting point for all journeys.”

Secondly, as Bornat (2016, 115) argues, children’s presence in the street and other community spaces is seen as a generator of social space: children’s everyday play can animate streets as they occupy pavements, gardens and driveways, and move between each other’s homes. Children playing out can draw adults out, as they watch, talk to, and care for their children. Where children play, adults meet. As Sam Williams argues, in the context of child-friendly cities, there is “enormous potential for child-centred activities such as play streets to bring people and places together” (Williams, 2017). Krista Cowman’s historical work draws attention to the key role of streets as ”social and play spaces in urban environments” (2017, 234), such that “mothers … saw play street orders as the best means to preserve them as a safe social space for themselves and their children” (251, emphasis added)

Thirdly, play itself has been identified as a catalyst for community such that the space, freedom, intergenerationality and looseness of play have the potential to create the space for connection (Play England 2015); as Play Wales (2015) suggest in a review of mental health and play, play can be seen, amongst other things, as ‘connection’ and ‘taking notice’.

Lastly, there is a need to think about and tease out the importance of children and of play – are they independent catalysts of relationships – i.e. is the presence of children enough, or is play essential too? In the context of street play, is it the children or the play that has the potential to generate ‘community’?

The Research

This post is based on a small-scale, qualitative, (auto)ethnographic and participatory project, developed with the existing North Tyneside street play organisers. It integrates data from a preliminary questionnaires, with both local and national participants, interviews with seven street activators in North Tyneside, running my own street play sessions, engaging in participant observation in others, and being involved in PlayMeetStreet North Tyneside, a voluntary group promoting and developing street play in the borough. As I mentioned above, this is very much an early take on the material reflecting really preliminary analyses – I haven’t yet had a chance to work in detail with the interview transcripts or fully analyse the questionnaires – this post is based on my immediate reflections on the research as it progressed and as I began to identify themes and ideas

Donald Winnicott and Potential Space

In thinking about all of these questions, I’m working with the ideas of Donald Winnicott, a paediatrician and psychoanalyst who was profoundly engaged in ideas about space, play and everyday relationships. Potential space is defined as:

“an inviting and safe interpersonal field in which one can be spontaneously playful while at the same time connected to others” (Casement, 1985, 162).

It is a liminal space, between (or perhaps across) an individual and their environment, located between or across the internal and external such that, for example, whilst at the theatre, we find ourselves simultaneously in the physical space of the theatre, in the imaginative space of the play, and in the internal, emotional space of our minds. Potential space is, of course, a space full of potential, where new relationships with ourselves and with others can be created. It is an area of experiencing, living, culture, creating – and, importantly, of relating and playing. To reiterate the quote above, it is a space in which we are “spontaneously playful while at the same time connected to others”, and in this we can identify an innate connection between play and relationships in potential space. The importance of play is founded on the presence of others who can receive, respond to, facilitate, witness, join in, celebrate, remember and enjoy the play and creativity, and playfulness creates an openness to new object relationships. Winnicott saw an innate connection between play and relationships, through the idea of potential space, which he saw as a space between people – children and adults – that is playful, safe, trustful, and creative. He believed play to be vital for those of all ages, seeing adult play – in art, creativity, humour, conversation – as equally important as children’s play in creating a liveable life.

I’m now going to shift to explore some of the key themes I’m beginning to identify in my research, organised around the idea of ‘hanging out’, of ’knowing your neighbours’ and of ‘crossing boundaries’.

Hanging Out

The idea and experience of hanging out is something which has garnered considerable attention from geographers of young people (see, amongst others, Fotel 2009; Pyyry and Tani 2017; Tani 2015; Tani 2016). In these literatures, hanging out is seen as a collective practice of appropriating streets, the creation of a liminal space for socialization with peers. The spaces of hanging out are theorised as “loose spaces” (Tani 2015) which enable those hanging out to deepen relationships with the city and “rework the atmosphere of the city” (Pyyry and Tani, 2017, 5) through deeply affectual “moments of joyous togetherness” (Pyyry and Tani, 2017, 5). Yet, these are also often spaces and practices which are theorised as the rejection of adult supervision and an escape from the adult world, which challenges the possibility of adult hanging out.

During a street play session, all that is expected of parents (or other adults) is that they are present on the street. The ‘playing out’ model assumes that parents are always present and responsible for their own children. Parents may play, with their children or own their own, but part of the ethos of street play is for autonomous child-led play, such that parents often stand back, at the side, letting the children get on with playing.

So adults hang out together, perching on walls, bringing out garden chairs, or sitting on curbs. Often they cluster around one house (often that of the organiser), where there may be drinks and snacks.

Parents are brought together, they’re present together, sharing a collective, familiar, public space, in a way that is legitimised by the presence of children, and in a space that is open, loose – and, of course, playful. As Cathy, who has been running sessions on her street for more than five years, explained when describing what a street play session feels like the sense of space is key:

Parents are brought together, they’re present together, sharing a collective, familiar, public space, in a way that is legitimised by the presence of children, and in a space that is open, loose – and, of course, playful. As Cathy, who has been running sessions on her street for more than five years, explained when describing what a street play session feels like the sense of space is key:

“Oh, it feels lovely, it feels wide, I mean that’s the first thing we all noticed the first time we did it, was how wide the street was … it’s quite a big space, normally it feels quite cramped and restrictive and dangerous. So, yeah, I think the feeling of space was the first thing.”

But parents also experience a different sense of time, a change of rhythm, a slowing down, in contrast to the routines of their everyday lives. Annie, for example, celebrated the slowed time of playing out sessions, where people can sit and chat and hang out, in contrast to the more ordinary experience:

“people are so busy, people don’t really have time for conversations, when you’re dashing to work and to school and things”

These were also spaces of play for adults too – playing with children, but playing with each other as well – scooter races, water fights, skipping, football, chalking, all of which appeared to allow for a different, looser kind of sociability than ordinary, highlighting the relationship between play and potential, play and others, and play and relationships.

As I’ve suggested, the presence of children seemed also to be key – adults were out because children were out and hanging out seemed to become problematic without children. Jenny illustrated this dilemma as she discussed how, towards the end of a street play session, she realised that her kids were no longer playing out (they’d gone to a neighbour’s) and suddenly she felt uncomfortable, being on the street, hanging out, without good reason.

Much of this resonates with Krista Cowman’s account of mid-20th century street play in which “children’s outdoor play facilitated women’s sociability and encouraged their use of the street” (p.236), enacted by women sitting on low walls, watching children play, and taking a break. In Cowman’s work and in the evidence presented here there are three key ideas: adults’ use of space; their use of time; and the presence of children.

Knowing your Neighbours

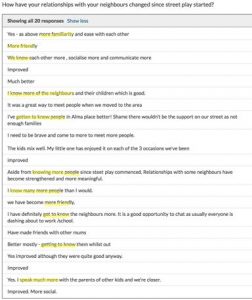

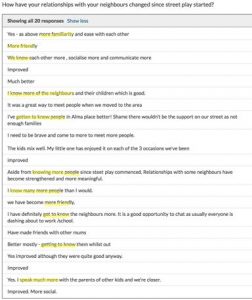

Here we turn to the question of what happens in these loose spaces of hanging out: what do the practices of hanging out do and what do they enable in the context of street play? It appears, following Tani and Pyyry (2017), that they reshape the spaces and atmospheres of the street, producing a particular kind of relationship between neighbours. In many cases, what is produced and remarked upon in questionnaire responses (see below) is a low-level notion of ‘knowing’ and ‘being known’, which appears to describe a level of recognition and familiarity of other faces on the street, between adults, between children, and between children and adults.

All sort of events, practices, moments emerge out of this knowing, but I want to focus in particular on the sense of safety experienced in this recognition. Respondents felt that they could address each other for help, of all kinds, and that their kids too would know neighbouring adults who they could approach for help. In interview, this was especially strong for those whose partners worked long hours or away, through a sense that they were known, seen, recognised on the street, and in this sense looked after, or contained. Annie explained:

“I like to know that if anybody needed, you know, help, you can go and call on anybody, my husband works long hours, I like to know that, you know, if we had some sort of emergency, I might just run down or across the street, give them a call”

In the immediate reports of change, then, a very particular kind of relationship dominated, but there were also many instances “when good neighbours become good friends” to quote a 1980s TV series. Relationships deepened, became more multi-stranded, and there was considerable socialising – between adults and children – outwith street play sessions, in homes, at the pub etc.. This step – the development of friendships – depended on and reflected much more personal connections, and was both enriching and excluding.

Crossing Boundaries

In the step between ‘knowing’ and ‘befriending’ boundaries, physical, social and emotional, became clear and flagged questions of what happens to those who aren’t included or don’t want to be? We see boundaries emerging in the delineation of friends and neighbours, but we can also see boundaries blurring and being crossed in the spaces of street play.

In a sense, we can characterise the street in this context as a micro-public space, following Amin (2002) – the street is a public space, it is not necessarily an intimate space, but it is at the same time a familiar space, an in-between, third space – between the internal and external, as Winnicott might have put it. The particular context of street play seems to make these boundaries more fluid, as there is license to move between the street and neighbours’ homes. Street play seemed to extend the publicness of the street to neighbours’ homes, to remove the barriers of invitation, but also seemed to domesticate the street by extending the atmosphere of the living room out. Living Streets (2009) describes our streets as “our extended front rooms” – street play extends our front rooms to the street and the street to our homes and gardens.

Amongst other transformations, interviewees reported:

- A noticeable opening up even in the act of doorknocking to arrange the first session – for many, this was the first time they’d walked up the paths, knocked on the doors, of all but their most proximate neighbours, the necessity to consult immediatey appeared to create the potential for new connections;

- Going to see neighbours extensions, gardens, renovations during street play sessions, when they had never been into each other’s houses before, and explored the resonances, the familiarity of visiting homes that were just like theirs, on terraced streets or twentieth-century semis – as Annie noted, “we have the houses in common”;

- Children moving between the street and homes or back gardens with thresholds being loosely policed – several adults reported popping in for something only to find half a dozen children playing inside, such that activities of street play for adults and children took place across and in between homes and the street;

- All of this activity during street play sessions extended beyond the session itself and resulted in more socialising between adult neighbours in their homes and more playdates between neighbouring children;

- And things and favours crossed thresholds too – there was more lending, borrowing, babysitting, and house/pet/plant-checking after streets had started playing out.

There are two important provisos to all this. Firstly, the fluidity reflected the physical layout of the street and the microgeography of the playing out session – certain houses and certain families, located around a key point on the street (often the middle of the street or the organiser’s home), were more likely to flow and be the sites of flow; those who lived further away could be both protected and excluded from these boundary crossings. Secondly, the boundaries were policed: respondents noted that there were limits to how many people (children or adults) they would want crossing their thresholds and to whom – less known neighbours, more unruly children, adults with whom you didn’t click might be excluded, deliberately or accidentally.

Imagined Futures

As the discussion of crossing boundaries suggests, the effects of street play extend beyond the three-hour sessions. These can be seen not only in the extended relationships, but also through tangible and intangible affective and material transformations in the street, and in the imagination of new futures for the street.

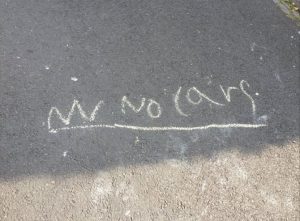

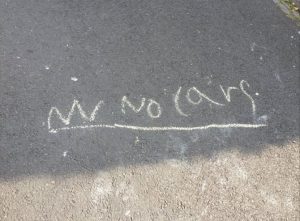

One of the most resonant aspects of this is chalk – almost every street chalks with abandon during the sessions – we give out chalk with our playing out kits – and this can last for days or weeks after the session, depending on the weather, a reminder of the street being transformed, different, something else. And, symbolically perhaps, this can persist even longer – this for example is the Google Street View image of my street – with post-street play chalk markings recorded with semi-permanence.

Other transformations are created in the street too, beyond the closure itself, including Facebook and WhatsApp groups bring neighbours together to share knowledge, concerns, favours, offers, recommendations, news, events, celebrations – and anticipations of the next session, and forms of everyday sociability – waving, saying hello, chatting, planning, banter and jokes – as neighbours walk to school, go in and out of houses, jostle for parking spaces, garden, and walk their dogs.

These develop and translate into imagined and potential futures as the possibilities of street play are felt. In interview, Annie deliberated on her family’s future housing needs, reflecting on their conversations about the value of the relationships they’ve built since they started playing out, and concluding that they envisage a future of staying and extending rather than moving:

“So we’ve been in this huge dilemma of, do we stay or do we move, do we extend, do we just buy a house and get a bigger bedroom, err bigger, more bedrooms and things but, errm, it’s the neighbours and it’s the area and you just think well actually it’s so important, erm, so we’ll look at some point we’ll probably end up doing an extension so we can stay and so we can be here…”

Others have started to discuss collective, street futures as playing out makes a space for new possibilities, for a more fundamental reclaiming of the street. On one street during a street play session, the adults turned the conversation to the possibility of closing the street permanently to cars, or implementing a partial or temporary narrowing of the street, shifting the balance further away from cars. Reflecting this, on another street a child – without adult prompting – chalked No Cars on the closed road. Playing Out itself proclaims “a vision of streets as vibrant, playable spaces” and plans for its own obsolescence: “ultimately, our aim is for playing out to be a normal everyday activity for all children, wherever they live, rather than an organised, supervised event”.

Playing Out itself proclaims “a vision of streets as vibrant, playable spaces” and plans for its own obsolescence: “ultimately, our aim is for playing out to be a normal everyday activity for all children, wherever they live, rather than an organised, supervised event”.

Potential Space? Play, Parents and Streets

This paper seeks to use Winnicott’s notion of potential space and its tying together of play and relationships to explore what happens – or what might happen – when streets play out. The decision and desire to create a space for children to play on the streets appears to legitimate the creation of a space on the street that differs from the everyday and permits the presence of adults as well as children on the street. In this context, the centrality of play creates an atmosphere of space, looseness, and informality, and a different kind of rhythm or pace, which enables both children and adults to have fun, and to have fun with others.

The looseness appears to facilitate a new kind of sociability, a new kind of contact and engagement which rests on a sharing, a being together, a recognition and familiarity and creates the potential for material, embodied and affective flows across thresholds, animating the space of the street and nature and density of everyday relationships on the street.

What is more, building on common understandings of play being the means through which children and young people get to know, to connect to and to deepen their relationships with their immediate environments, I also want to argue that street play enables adults to connect to their streets too, to become more attached to their streets, to know their streets better and, thus, to experience their streets as spaces which have the potential to hold and contain them.

In this sense, street play can be seen as a radical act, full of potential, which can reshape affective atmospheres and spaces of the street

But it not without its challenges and limitations – and I just want to touch here on an important issue – a great deal of what I have discussed here is classed and gendered, at the very least. Playing out might be seen as middle class phenomenon, reflecting the different modalities of autonomous street play in neighbourhoods with different class profiles – it is not quite as simple as this (see, for example, this report on playing out in disadvantaged areas and this from Playing Out on street play on estates), but thinking through questions of class is an important part of my ongoing analysis. And secondly, much of the energy and labour invested in playing out is women’s – of 22 streets in North Tyneside that have played out over the last three years, just two street organisers are men; and, of course, Playing Out was founded by two mothers, Alice and Amy. Men and women appear to take on different roles during sessions, and are differentially engaged in what extends from the sessions into the everyday life of the street, so this is not to say that men aren’t involved nor that street play is not transformative for them, but again, a gendered analysis will be critical.

Notwithstanding these caveats, I argue that planning and doing playing out sessions reshapes everyday relationships on streets, creating the potential for new forms of sociability, care, connection, and fun, which in turn transform the space of the street to one of potential and possibility.